Cycles of Waste Wood: Low-Cost Construction and the Disposable House

Masonite House at the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago.

“Masonite: A Souvenir of the 1934 World’s Fair,” fair literature created by the Masonite Corporation, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1934.In late 1994, homeowners in two Alabama counties allied themselves in a suit against the Masonite Corporation. They alleged that the composite wood-fiber material used as siding on their homes was intrinsically defective and subject to rapid deterioration. As one of the original plaintiffs pithily summarized, “It just rots and falls apart.”1 Affected parties across the country signed on to a class-action lawsuit, and its billion-dollar settlement in 1998 was one of the largest in history.2 Speaking to the press in 1995, one of the plaintiffs’ attorneys outlined the complex array of legal issues represented by this case. Central to the lawsuit was the composite wood material sold under the trade name “Masonite hardboard.” As a low-cost engineered product replacement for expensive milled lumber, the Masonite material saturated the lower-end housing market. Due to the product’s porous nature, however, moisture saturated it as well. In the mid-1990s, high turnover in the ownership of these homes—every five to six years on average, due to a pattern of obsolescence and upgrade—frequently distanced the original purchaser of a house with the defective Masonite siding from those who would experience the product’s material failure.3

Masonite hardboard is made of compressed wood fibers. The product is one of the many inexpensive wood-based engineered materials that have become ubiquitous in the low-cost housing market in the United States. Fiberboard, hardboard, particleboard, waferboard, oriented strand board—the names for these materials marry a generic descriptor of material makeup with the intended constructional use (“board”). Between the 1950s and the 1990s, these wood fiber materials gradually replaced solid wood in furniture, cabinetry and doors, flooring, sheathing, and siding and did so in tandem with the increasing scarcity and expense of the solid lumber that would previously have been used in these applications.4 Throughout much of the twentieth century, these engineered building materials were associated both with forest conservation and with bringing home- and home-goods ownership within reach of a broader segment of the US population. As Janet Ore has noted, in the years following World War II, “engineered woods like plywood and particleboard made possible the construction boom and democratization of ownership that marked the cold war era.”5 However, this democratization of ownership has also introduced a pervasive, low-grade, and almost banal toxicity into a substantial proportion of the lower-cost houses in the United States. Unlike many engineered wood products, which contain chemicals that are toxic to the human body, the toxicity of much of the reconstituted wood that was used in the construction of the twentieth-century low-cost home was in the sense of a “toxic asset”—an investment that rapidly and unexpectedly degraded in its value, in this case with very clear effects on human lives and welfare. Fully imbricated in a commercial culture of obsolescence and upgrade, cheap wood-fiber–based sheets have helped normalize the idea of a continual degradation and necessary replacement of the materials in the US home and its interior. The early and easy failure of many of these materials is both commonplace and unremarkable but also, to paraphrase a legal summary on product liability, the cause of trauma and harm.6 Since the final years of the twentieth century, nearly every major manufacturer of composite wood cladding used in the housing market has been sued for defective products and premature material failure that has often led to home and property damage.7 To be clear, however, while the chemicals and components in the material are understood to be nontoxic, the decay (of value, health, and the material itself) yielded a form of slow, insidious, and utterly normalized harm.

In their propensity for premature failure, these cladding products are closely related to the particleboard that comprises modern “fast furniture” (i.e., quick to manufacture and quick to the dump), as well as to the plywood and oriented strand board cladding the interior of many postwar houses, in particular mobile homes. In contrast to Masonite, which is not chemically toxic, many of these engineered wood materials infuse interior domestic environments with chemical toxicity as well: because of its high formaldehyde content, particleboard, for example, is regularly on the short list of products that may cause poor indoor air quality.8 Furthermore, interior particleboard’s formaldehyde-based adhesives have themselves been intensively cost engineered since their widespread adoption in the 1960s, leading to more economically accessible furniture and finishes and more biologically accessible airborne carcinogens in the form of volatilized free formaldehyde.9 This chemical/bodily toxicity and the more insidious toxicity of easy material failure of early Masonite both rely on a paradigm of disposability—of materials, objects, and homes. In this essay collection, Janet Ore explores how the relentless speeding up and value-engineering of plywood manufacture effectively required a mind-set of disposability toward not only products but workers’ bodies as well.10 Rapid production of disposable homes and home goods introduces toxic disposability at all scales.11

As Pamila Gupta and Gabrielle Hecht have observed with regard to toxic waste, looking at waste-making makes legible the “‘slow violence’ of fast capitalism.”12 While far less acute than the toxic geographies studied by Gupta and Hecht, as well as others, many engineered woods demonstrate similar patterns in their histories, legacies, and geographies of waste. Hardboard, particleboard, and other inexpensive sheet goods are no longer associated with the ostensibly altruistic goals of making housing more financially accessible while productively addressing waste-generating practices in lumber manufacture. Instead, these low-cost products frequently enable speculative mass construction of houses that are built to a quality standard that ensures they only last long enough to provide the builder with a profit. In normalizing such disposable homes, these products enable and sanction mass consumption and waste-making practices in (and of) that historically most hallowed of places, the home.13

Hardboard siding and particleboard furniture have become shorthand for a material culture characterized by low initial costs and a short horizon for replacement. Both circumstances are emblematic of a mentality that considers the built environment eminently disposable, a mind-set that causes harm on multiple fronts. For decades, homeowners have watched the exteriors of their homes bulge, sag, and rot, while wondering whether the particleboard making up much of their furniture was slowly making them sick.

Standard building practice began to incorporate wood-based sheet goods in the early twentieth century, when their innovation answered popular demand for efficiency, thrift, timber conservation, and waste reduction. As they were widely adopted over the subsequent half century, it became apparent that these materials often caused substantial harm. How can we account for the distance between the ideals that prompted the innovation of these materials and the widespread negative impacts of their adoption?

The Mores of Less: Waste-to-Waste Ethical Ambitions

A sawing diagram for lumber parses the parts of (monetary) value from the rest, indicating the way in which different cuts of solid lumber are positioned within the trunk of the tree. The spaces between and around these diagrammed solid boards are rendered as sawdust, chips, and slabs (or, in some descriptions, “scabs,” the bark-heavy offcuts that are left when timber is squared). The harvesting of timber from the forest also entails the separation of the parts with commercial value from the rest; limbs, small or irregular trees, and stumps are typically left on the forest floor when the salable timber is taken.

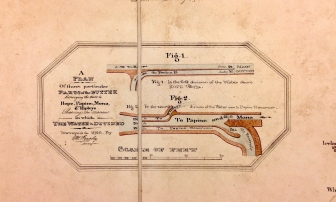

Fig. 1. Wood Conversion Company (WCC) Offal Machine.

Howard Frederick Weiss/Wood Conversion Company, “Utilizing Wood Waste,” US Patent 1,631,172, filed May 19, 1921, and issued June 1, 1927.

In May 1921, the Wood Conversion Company received a patent for a process, mechanism, and final product entitled simply “Utilizing Wood Waste.” The patent text began by noting the “large quantities of what may be termed saw mill offal or wood waste, such as slabs, edgings, trimmings, sawdust, shavings, and bark,” as well as “paper maker’s waste, such as crooked bolts, saplings, and the limbs and branches ordinarily left in the forest.”14 The process entailed passing the wood waste through a “hog” (a chipper or shredder) until it was reduced to small slivers and particles, which would then be sorted by screens into very fine “fiber aggregates” and the slightly larger “small wood particles” (fig. 1). The fiber aggregates would then be continually macerated, with the addition of water, until the naturally present lignin became hydrated, producing a “resultant product [that] is a slimy gelatinous mass of lignocellulose.”15

When dried, the gelatinized lignocellulose held the wood particles in a hard, smooth, and “bonelike” matrix, which, the patent claimed, would not shrink like regular lumber and performed well as an insulator of sound and heat. A rich uniform brown, the surface of this new board was, according to the patent, simply “beautiful.” Waste, via this new offal machine’s process of grinding and wetting, was transformed from a substance of little to no monetary value (waste had typically been burned) into a “novel and valuable product.” This process, in the forest products context, is called “conversion.”16

Conversion is an ostensibly anodyne agricultural term that somehow holds an abundance of unquestioned values. One can convert corn into whiskey, a tree into lumber, or a living, mooing cow into steak, burgers, and brisket. Physical matter is converted into something else, typically something with a more specific use. Conversion also affects value. There are myriad ways to value a tree or a forest, from the spiritual, to the ecological, to the tax assessed on the land.17 When forests are converted to lumber, their value is determined in a fixed way, albeit by a highly variable market. A rich yet nebulous range of values is simplified and rendered precise by conversion, and the economic value of the material is typically enhanced. In 1921, the year of the wood waste patent, eleven companies (including Weyerhaeuser) had incorporated as the Wood Conversion Company. Headquartered in Cloquet and St. Paul, Minnesota, the company would last in its original incarnation until the late 1960s.18 In the decades following its incorporation, the Wood Conversion Company received nearly 350 patents for new or improved wood-based or farm waste-based products. As with the 1921 offal machine, these patents were for waste-based materials that were pressed, squeezed, baked, or otherwise shaped into forms destined for use in the construction industry.

Beginning in 1925, just a few years after the incorporation of the Wood Conversion Company, William H. Mason of the Masonite Corporation received a series of patents for pulping and felting wood fibers into thick sheets. While wood, due to its high lignin content, was the preferred base material for Mason’s process (which would fuse the fibers back together under heat and pressure), his patents also reinforced the fact that basically any inexpensive “vegetable fiber” could be pulped and turned into a product, with the “obvious . . . great advantage to cheapen the cost of manufacture so that the product can be placed on the market at a low price and used for purposes in which large quantities are dealt with, for example, the roofing and flooring of buildings, and the exterior and interior walls thereof.”19

Fig. 2. Mason Thick Sheets Apparatus.

John A. Wiener, Assignor to Masonite Corporation, “Method and Apparatus of Forming Thick Sheets from Pulp,” US Patent 1,853,185 filed May 24, 1927, and issued April 12, 1932.

Masonite Presdwood was developed in 1928, followed several years later by Tempered Presdwood, which was a harder and more durable version (fig. 2). The impetus for developing these two products matched what the Wood Conversion Company sought to do: develop low-cost construction products through the use of low-value organic fibrous matter. By the beginning of the 1930s, Masonite patent applications were clearly describing this reconstituted wood waste as a one-to-one replacement for nonstructural solid wood, often referring to it as “artificial lumber.”20 During this time, demand for an artificial lumber, particularly one manufactured with and thus reducing wood waste, would have been widespread. The 1920s witnessed an expansion and intensification of forest conservation efforts that had begun in earnest around the turn of the twentieth century.21 The compelling specter of a timber famine, an idea strategically popularized by Gifford Pinchot and Theodore Roosevelt at the turn of the century as a lever toward greater federal oversight and control of the nation’s forests, reared its head with force in the 1920s.22 Two pathways toward saving wood (and thus saving the forests) were frequently outlined during this period: wood preservation and higher, better wood utilization. Higher and better utilization of wood pivoted on the reduction of waste. A crucial pathway to waste reduction lay in the standardization of lumber: common sizes were established so that mills could provide uniform boards. This push to standardization, amplified during World War I, was exemplified by the Division of Simplified Practice, a project of the Bureau of Standards initiated shortly after the war ended. Established by Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover in 1921, the division was a resource for industries interested in “applying the principles of simplification to their businesses” and, in so doing, participating in the “steady elimination of our economic wastes.”23 In the context of building materials, this federal effort entailed precise recommendations on how to simplify or reduce variety in building materials. For example, in its 1924 report, the division recommended that paving brick be reduced from the 66 varieties then available to 11, metal lath from 125 varieties to 24, and face and common brick from 75 varieties to a single rough and a single smooth variety. Variety in lumber, the report claimed, had been reduced by 60 percent since the adoption of the division’s recommendations several years earlier.24 In 1925, the changes augured by the Division of Simplified Practice were also referenced by William Greeley, then chief of the US Forest Service, as enabling “the elimination of waste and simplification in wood-using industries” (fig. 3).25

Fig. 3. Simplified building materials, Division of Simplified Practice.

Albert Farwell Bemis and John Burchard, The Evolving House, vol. 2, The Economics of Shelter (Cambridge, MA: The Technology Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1933), 166.

In wood-waste reduction, simplification and standardization applied not only to size and strength but to grade. This meant using a quality of wood that was deemed appropriate to the perceived importance of the use. As John Gries, of the Division of Building and Housing in the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Standards, argued at the 1924 Wood Utilization Conference, farm buildings, “temporary shacks,” and other low-value construction did not require “clear, practically flawless lumber” and “to use clear stock for such purposes is a waste that should not be countenanced now.”26 The value of the lumber, the argument went, should match the value of the construction, and evidently not everyone was entitled to the best. In this framework, Gries and his colleagues at the Division of Building and Housing believed that cheapness, properly allocated, was a pathway to the moral high ground of waste reduction. Gries’s allocation of cheap material to low-value construction also might be understood as aligning low-value construction with temporariness (“shacks”), which conflated waste utilization with both low-cost and rapidly degraded or obsolescent architecture.

Waste Wood and the Low-Cost House

The lowest-value raw wood material was the “wood offal” that existed in the gaps between prime lumber cuts. Artificial lumber made from this material—by the Wood Conversion Company’s offal machine and its successors—was ideally suited for the low-cost house. In 1933, the Masonite House joined a host of industry-sponsored low-cost houses on display at the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago (fig. 4). This world’s fair occurred at the height of the Great Depression, a time when an acute sensitivity to the design challenge of the low-cost home permeated the American architectural consciousness.27 This interest in the economy of home design, initially focused on space planning and façade simplification, rapidly shifted toward a focus on materials and construction systems, especially on the production of low-cost building systems.

Fig. 4. Masonite House at the Century of Progress International Exposition in Chicago.

“Masonite: A Souvenir of the 1934 World’s Fair,” fair literature created by the Masonite Corporation, Chicago, Illinois, ca. 1934.

This tendency became apparent in undertakings such as Fortune magazine’s 1932 series Housing America, which sought to leverage underutilized industry in the production of a low-cost and commercially viable mass-produced house. This was a design challenge yet “decidedly not an esthetic problem but an industrial problem.”28 Similarly, Albert Farwell Bemis’s Evolving House series reckoned that the solution to the US housing crisis would “be accomplished through industrial and engineering efforts.”29 Along the same lines would be the experiments—peaking between 1932 and 1939—of the John B. Pierce Foundation in using new panel products in the construction of low-cost houses.30 The large, flat, uniform, and dimensionally stable sheets made by Masonite and the Wood Conversion Company were perfectly suited to emerging interest in material simplification and standardization, rapid and low-cost construction, and modernized home styles.

In the early years of experimentation, sheet-constructed houses demonstrated a planar and prismatic appearance, visually similar to what is frequently associated with the so-called International style architecture that emerged during this same period. However, the differing ideological underpinnings of these superficially similar approaches to building were substantial. This difference is illustrated by an Architectural Forum announcement of the formation of the Albert Farwell Bemis Foundation in 1938: “Two wide paths lead the way to successful low-cost housing: Government subsidy and technical improvement of Building’s material and methods. Month ago [sic] President Dr. Karl Taylor Compton announced that his Massachusetts Institution of Technology had set foot on the second path with the establishment of the Albert Farwell Bemis Foundation.”31 The modern scientific houses promoted in Albert Bemis’s series The Evolving House and Fortune magazine’s Housing America were characterized not just by smooth, cubic surfaces and the absence of ornament but by a firm belief that industrialization of building material manufacture and construction systems—not government assistance or aesthetic and design innovation—would be the “turbine” to lift the United States out of economic depression.32 This faith in the transformative power of modern materials extended to and effectively subsumed the design process itself: the third volume (subtitled Rational Design) of Bemis’s three-volume Evolving House series concluded with the proposal that future construction standards be formulated on a basic four-inch module that would “provide the basis for a sound standardization of all dimensioned building products with at least as great flexibility of building layout as was available with former ‘stock’ sizes.”33 This approach, which Bemis named the Cubical Modular Method, collapsed any conceptual distinction between building material modernization and the resultant standards governing the design process and, eventually, building design. Similarly, the early General Houses models shown in Fortune magazine’s Housing America were named with a precision that gestured toward full simplification of materials and aesthetics. Housing America introduced one such prototype, called the K2H4O model, stating that this “architectural formula” (as opposed to a chemical formula) would elucidate both the logic and the form of the resultant house.34

This faith in industrially led solutions to the economic and housing crises frequently pivoted on material innovation and the desire for new manufactured wonder materials to undergird the mass production of the scientific house. Alongside claims of their miraculous toughness and range, advertising for these new materials seemed designed to instill a sense of anticipation, aligned with a general optimism about how the new human-made materials of the future might change the American home.35 Masonite Corporation literature from this period demonstrates how thoroughly the company bought into the notion of the all-purpose wonder material. It is exemplified in the Masonite product tagline “the wonderwood of 1000 uses,” as well as another frequent advertising claim that “Tempered Presdwood out-weathers the weather.” The Masonite House at the 1933–1934 Century of Progress Exposition was leveraged as built testimony for the durability and versatility of the material. As one pamphlet stated, “[The house’s] Masonite Presdwood exterior was erected last summer, left bare and unprotected through the winter. It was unaffected by the freezing mist and spray from the lake. Its smooth coat of paint, applied in May, will not chip, crack, or blister.”36

Advertisements in architectural and shelter magazines during the 1930s and 1940s similarly focused on the durability of the Masonite siding, as well as the lower installation and labor costs associated with its use. One advertisement from Better Homes and Gardens magazine in 1941 described a “9-year bath” taken by a piece of Masonite Presdwood, after which “this remarkable material … had retained 80% of its original strength … [and] when dried, was within 1/10,000 of an inch of its former dimensions,” having an “appearance [that was] practically the same as when submerged.”37 Another pamphlet from the 1930s enumerated twenty-eight reasons to use Masonite Presdwood. Taken together or parsed individually, the items on the list exude the materiality of architectural modernism: smoothness, ease of use, ease of disinfection, and dimensional stability. Reason no. 25 on the list confidently proclaimed that the manufactured siding product “defies time” (fig. 5).38

Fig. 5. “28 good reasons why you should use Masonite Presdwood Hardboards.”

Masonite Corporation, “How to Repair, Remodel, Build on the farm with Masonite Presdwood … the wonderwood of 1000 uses,” promotional literature, ca. mid-1930s.

The rhetoric of supernatural material capacity that made Masonite so popular for “1000 uses” meshed with an ongoing appeal to its sylvan origins. In many ways, the woody appearance of Masonite and other wood-based sheets complicated the narrative of material and industrial modernization intrinsic to many of these house projects. While the smooth, planar surfaces that these materials produced with ease were resonant of the white cubic planes of early twentieth-century modern architecture that had been laboriously created with brick, concrete, and stucco, Masonite and other wood-based materials were often left unpainted and glowingly described in terms of their warmth and richness.39 Projects such as the Masonite House built for the Century of Progress were described through the abundance of Masonite surface left “natural” (unpainted).40 The Masonite House itself, designed by the Chicago firm Frazier & Raftery, initially exhibited a highly simplified façade—a planar enclosure interrupted only by the carefully expressed joints in the Masonite cladding, arrayed like an oversized grid over the entire exterior. Later photographs depict the exterior painted white and the modularity of the cladding material minimized. The smooth, panelized cladding approach continues on the interior, with chrome and aluminum battens covering panel joints and contributing to a highly modular appearance. Large expanses of glass and corner windows underscore the modernist stylistic ambitions of the architects.

Despite its ready use in designs that strategically superimposed new materials and construction systems onto a stylistic expression of architectural modernism, such as that of the Century of Progress house, Masonite as a building material would eventually find more humble contexts in its widespread implementation. This shift from high design concept to utilitarian design was, in a way, a logical outgrowth of the product’s versatility and capacity to serve as a wood replacement, just as wood had had centuries of association with experiments in low-cost single-family construction in the United States.41 Another experimental house, from a decade later, demonstrates more common outcomes for the so-called wonderwood. The Herdsman’s House, clad inside and out with Masonite, was designed by Boston-area architect Eleanor Raymond for her client Amelia Peabody in 1944 and constructed in 1946. Intended to shelter one of the client’s farmhands, the project was one of several experimental designs Raymond built for Amelia Peabody during the 1940s, among them a solar house and an all-plywood house.42 Like Raymond’s Peabody plywood house, the Masonite Herdsman’s House at the Peabody farm was meant as a prototypical outbuilding and as a way to develop a set of low-cost building and detailing approaches.

The experimental mind-set of the Peabody-Raymond duo comes through in Raymond’s description, offered later in life, of the genesis of the project: “They were advertising that Masonite could be used for different parts of a house. And Amy Peabody said, ‘Oh, l’d like to do that.’”43 Peabody went on to insist, to the seeming chagrin of Raymond at times, that every aspect of the Herdsman’s House be built of Masonite—even the kitchen counters and floors. The aspiration to a wonder material of “1000 uses” found architectural expression in Raymond and Peabody’s version of the Masonite House, but the form of their house and manner in which the material was used differed significantly from the modernist disposition of the Century of Progress prototype. With a pitched roof, symmetrical façade, and horizontal board siding, the Herdsman’s House looks unremarkable for a 1940s dwelling, in most ways. An exception is the scale of the horizontal Masonite sheets cladding the house. Although detailed like standard clapboard siding, each board is approximately two feet in vertical width. The effect is slightly uncanny—a well-known type of wooden siding, dimensionally shifted to an application that would have been impossible. Looking at this gigantic aspect of the siding, it is hard not to see a harbinger of imitated, improved, and reconstituted wood shoehorned into the timeless architectural idiom of the low-cost wooden house.

The legacy of these experimental houses and many others like them, which mainstreamed the idea of a low-cost engineered wonder material as crucial to the future of the affordable house, played out over the ensuing decades. A crucial material in low-cost and rapidly deployed wartime structures, especially Quonset huts, Masonite hardboard would be widely incorporated into low-cost furniture and finishes throughout the mid-twentieth century.44 The cheap raw material for William H. Mason’s artificial lumber and the Wood Conversion Company’s offal machine was abundant—a host of material by-products generated around the processing of the “prime cuts” of lumber that went to higher bidders.45 Like the “mystery meats” offered by agribusiness for the budget-conscious shopper—hot dogs, SPAM, bologna—and the other cheap, heavily processed goods of modern life, waste-based building products were not a matter of choice for the cost-conscious consumer in the midcentury United States.46 By the time these manufactured wood-waste “cheap sheets” were part of the furniture of US interiors and the face of US houses, they were, for many, often the only financially viable option.

Litigating Decay

William H. Mason’s 1920s patents for thick sheets made from felted wood fibers opened the way for production of an artificial lumber that might be used in “large quantities [such as] the roofing and flooring of buildings, and the exterior and interior walls thereof.”47 The Masonite House displayed at the Century of Progress Exposition in 1933 was a constructed argument for the versatility and durability of the miracle material, and trade and advertising literature in the years before and decades following the exposition continued to underscore the apparently remarkable qualities of this “wonderwood.” As Masonite continued developing its product for exterior use over the next few decades, the exact language of these claims to durability, versatility, and material improvement over traditional wood products would become central to how the failure of the product and the culpability of the company would be legally described.

Masonite was not the sole target of public outrage over the failure of its siding products. Beginning in the 1980s, plaintiffs initiated a steady stream of individual and class-action lawsuits against manufacturers of wood-composite siding.48 Louisiana-Pacific, makers of an oriented strand board siding product, settled one case for $275 million in 1996 and paid out $37 million when it settled another in 1998.49 Weyerhaeuser similarly settled a class-action suit in 2000 for siding that became swollen and rotten when exposed to water.50 Although these seem like massive settlements, the problem was so extensive that one reporter noted that these amounts were increasingly criticized as “grossly inadequate.”51

The suit against Masonite/International Paper followed a similar pattern, with a small group of homeowners led by Judy Naef in Mobile, Alabama, initially suing the company in late 1994. As additional plaintiffs signed on in the following year, the plaintiffs’ attorneys sought to elevate these suits to a class action, which was granted in early 1996.52 The plaintiffs claimed that the hardboard siding produced by Masonite swelled when exposed to moisture and began to rot, rendering the siding ineffective as a weather barrier and frequently causing damage to other parts of their homes.53 In the trial, held in 1996, a jury determined that the siding was in fact “defective,” a definition that included five separate operative definitions, including whether the expectations of an “ordinary consumer” of the material were met and whether an “ordinarily prudent company making exterior siding, and being fully aware of product failure, would not have put the hardboard siding on the market.”54

Fig. 6. Masonite legal ad language.

Second amended Class Action Complaint: July 3, 1996, Mobile County District Civil Court.

The language used in Masonite’s marketing literature for the siding products figured prominently in the final class-action complaint, with two full pages of quotations made in the Sweet’s Catalog included as evidence of the express and implied warranties that had been violated (fig. 6). Claims such as “hardboard is real wood” and that the manufactured wood product is “stronger and more durable than the wood from which it is made” were no longer just the overexuberant rhetoric attending the material improvement frenzy of the 1930s and 1940s.55 They were claims that had led people, often with limited means and savings, to make the investment of a lifetime in their home. They were claims that, when they fell short, caused consumers to witness the deterioration of their houses and that led to millions of board feet of the siding ending up in Dumpsters and landfills.

In lieu of returning to a second trial to determine damages, International Paper elected to settle in 1998, opting to pay the plaintiffs’ $47 million in legal fees, as well as any valid claims that would likely result from the settlement—a total that Masonite estimated at the time would top out at $150 million. To evaluate claims, an independent inspector was assigned to each plaintiff’s property to determine whether siding failure had occurred; if it had, Masonite would be required to pay each plaintiff’s damages.56 Since the original settlement in 1998, more than four million affected homeowners have made claims of defective hardboard siding manufactured by Masonite, and total cash paid out exceeded $1 billion in 2023.57

Even with the settlement, homeowners continued to find the amount offered to be inadequate and sometimes even insulting. The Circuit Court of Mobile County was copied on numerous homeowners’ appeals to the independent inspectors assigned to Masonite cases, describing the frustration of the low offers made for the repairs. One retiree described the impact of the “potential of deterioration even if not visible.” After the investigator’s simple visual inspection of the exterior, this homeowner had been offered $286.50 to replace just the small area of siding that was visibly deteriorated. She had this to say:

I will be 77 yrs. old in September and thus being a retired senior citizen, there is no way on earth that I would ever have thousands of dollars to rebuild the exterior of my house … a house that was only 5 years old when all this deterioration was starting all around me. I took all my savings to build a retirement home, and how horrible it is to know it will deteriorate all around me and lose the value of my home … and deteriorate it will! Even if I chose to sell at this point, it would be impossible to sell with a class-action lawsuit hanging over the property.58

The looming potential for deterioration had been the subject of much of the Masonite trial, especially in the attempt to define material failure. The plaintiffs’ building science expert had claimed, much in the manner that this letter writer had, that Masonite must compensate customers for “nonmanifest” damage, that is, microscopic ways in which a material had begun the “inexorable process of failure, even if such failure is not yet obvious.”59 The retiree, living with the knowledge that her home would “deteriorate all around” her was already experiencing harm from nonmanifest damage via her knowledge of it.60 The plaintiffs’ argument for financial compensation for nonmanifest harm used evidence from another materials-based lawsuit, filed against Johns-Manville in 1985. In this case, the plaintiff had inhaled asbestos fibers on the job but had not yet developed a disease related to asbestos inhalation. According to the court, even though the plaintiff was not (yet) manifestly sick, his lungs had been scarred and physical damage had been done—that is to say, there was legal protection for what were called “inchoate wrongs.”61 Harm, even inchoate and nonmanifest, thus had legal precedent when it was harm to the body. When what was harmed was instead a sense of being protected from the “inexorable process of failure” of one’s home, the damages were less clear.62 Inhalation of asbestos fibers is more acute than a loss of security due to a home’s declining value, but if these things are considered in a continuum of harm, the cheapness and quick degradation of these materials becomes legible as a form of toxicity.

Elizabeth J. Cabraser, one of the original attorneys on the Masonite case, later wrote about liability involving new building products: “When most of us think of products liability, particularly in the context of mass torts, we think in terms of personal catastrophe: mass accidents, toxic exposures, and deaths and injuries from dangerously defective products. But what about those other mass torts, where products break or fail to perform as expected, but ‘nobody’s hurt’?” She also referenced the host of novel building products that in recent decades had become “widely available and are aggressively promoted by manufacturers,” arguing that “when these products fail in service, they rarely cause catastrophic injury, but the experience of a deteriorating home or apartment building does cause trauma, concern (and economic loss and/or property damage) more acute than that accompanying a malfunctioning toaster.”63

A 1998 Wall Street Journal article covering the Masonite case (aptly headlined “When Dream Products Turn into Nightmares”) asked, “Is your house ‘composite’? Will the stuff fall apart?”64 According to the range of lawsuits mentioned in the article, it seems very likely that a “yes” reply to the first question would be followed by a “yes” to the second. Another secondary headline to the article promised information on what to do if your Masonite products fall apart, but the article’s coverage of recent litigation implied there was only one option: if your house turns to mush, all you can do is sue.

Toxics and Material Obsolescence

Composite siding, and Masonite specifically, is not associated with the physical-bodily-chemical toxicity that characterizes many of the engineered wood products of the mid- to late twentieth century. However, its ultimate effects—alienation from one’s home and compounded precarity—are usefully compared. Janet Ore and Nicholas Shapiro, among others, have documented how the somatic and psychological effects of living with formaldehyde create or exacerbate housing and health vulnerabilities in those living in and with these homes.65 As Ore’s research has shown, the off-gassing of formaldehyde in many postwar mobile homes was unregulated by codes and left buyers with little recourse except individual lawsuits. Legal action by those suffering the health effects of off-gassing was crucial to raising awareness around the dangers of living with these toxic fumes but remained out of reach for many.66 Shapiro has also noted the relationship between precarity and material toxicity in his ethnographic work on formaldehyde exposure, stating that “formaldehyde concentrations were both indicators and agents of social abandonment and precarity.”67 This suggests that cheap building materials and assemblies, whether exhibiting physical/chemical toxicity or a more insidious toxicity of quick material failure, are together the cause, index, and effect with regard to vulnerability in one’s domestic environment.

Toxics literature focused on the slowly accumulating and subtle harms deriving from seemingly innocuous material assemblies can explain another danger of deliberate material degradation: the degradation of the security and stability ostensibly offered by the single-family house. This precarity is coded into many low-cost materials made of reconstituted wood, whether or not that precarity takes the form of negative health impacts (as with formaldehyde exposure) or entails living with the certainty that your home is degrading faster than one would expect and you will not be compensated for the loss. The framework of residues, used by many scholars for these persistent, accruing, deeply rooted, and hard-to-see harms, helps to clarify the impact of cheap sheets on human lives. Residues have been a broadly helpful frame in “help[ing] us see how the past has been built into our chemical environments and regulatory systems.”68 Among the researchers producing this growing body of literature on residues, Soraya Boudia et al. describe how the historic de-valuing of people and places, as well as the nonexistence or dismantling of regulatory practices that govern their care, materially persists in the waste and contamination of these areas as residues. To call something a “residue” means that its useful life is effectively over—that it has aged, moved on, or is otherwise to be disregarded. This, coupled with Gupta and Hecht’s exploration of the relation between waste versus value, slow violence, and fast capitalism helps us see that the destructive cycles embedded in the material impermanence of many low-cost construction materials perpetuate harmful impacts on those who live with them and who live with the fear and knowledge of impending material failure.69 The regulatory systems referenced by Boudia et al. might be expanded to include lucrative patents, lenient building codes, short-term and profit-extractive material assemblies, and the normalization of speculative housing built with a fifteen- to twenty-five-year intended design service life—a “design life” that is coded into both the financial instruments enabling these profit-seeking ventures and the very materials with which they are constructed.

In the introduction to this series, Meredith TenHoor and Jessica Varner note that “developing architectural historiographies and methodologies of toxics requires listening to, learning from, and honoring work from other disciplines.”70 Simultaneously, a central question of the project pivots on what the methods intrinsic to architectural and landscape history might offer this already robust discourse. Environmental and social histories of housing in the United States have explored the manner in which more housing for more people at a lower cost emerged as an unassailable and implicitly virtuous architectural endeavor during the 1920s and 1930s.71 Methods more common to environmental history and STS help elucidate how the social aim for more housing was wedded to contemporaneous goals of forest thrift, widespread standardization of building practices, and material efficiency, resulting in a panoply of new wood-based materials and building systems.

These methods allow us to constellate original aspirations against eventual outcomes in a more holistic framework: particleboard and other composite forest products were first imagined in the United States in the context of a country newly aware of the limits of its natural resources, specifically its forests. Material innovation brought forth these products in response to the desire to waste less. Dozens of patented devices for reconstituting waste wood, continually refined manufacturing processes, and an evolving cast of chemical additives made this wood waste into a material that was lightweight, dimensionally stable, easily worked, and, most important, low in cost. These processes fundamentally sought to increase the economic value of their base material through conservation and conversion, and these products were promoted in the US imagination as “wonderwoods” that would replace and thus conserve solid wood from the nation’s forests.72

However, as easily as this value was created, it began to degrade, which is where frameworks like toxics and residues help us trace the implications and nefarious agencies of these woody waste particles as they became widely incorporated into the American constructed environment.73 Their natural propensity to absorb moisture, alongside the intrinsic chemical instability of their urea formaldehyde binders, meant that this value-added waste wood was frequently transformed into products that themselves quickly rejoined the waste stream. Intrinsic to the materiality of reconstituted wood, it seems, is the rapidity with which its value—and the value of the things made from it—degrades, wasting away as composite siding and particleboard furniture bulges, frays, and sags. Writing material degradation and its human effects into the architectural history of the American house adds to the growing literature that also explores the more explicit toxicities attending this typology, introducing the history and context for a set of processes that are difficult to see, yet similarly harmful in their ultimate effects.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Erin Putalik, “Cycles of Waste Wood: Low-Cost Construction and the Disposable House,” Aggregate 12 (December 2024), https://doi.org/10.53965/NUIR4706.

- 1

Alabama attorney John Crowder, quoted in Pete Zurales, “Masonite Being Sued by Alabama Homeowners for Alleged Defects in Hardboard Home Sidings,” Mobile (AL) Press-Register, August 25, 1995.

↑ - 2

“Alabama Court Certifies Class Action Suit for Homeowners Nationwide: Damage Claims of Owners of Structures with Masonite Hardboard Siding Now Covered by Naef v. Masonite Corp.,” PR Newswire: Financial News, March 12, 1996.

↑ - 3

Zurales, “Masonite Being Sued.”

↑ - 4

For a timeline and a discussion of how particleboard innovation preceded its widespread adoption by at least fifty years, see Thomas M. Maloney, Modern Particleboard and Dry-Process Fiberboard Manufacturing, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Miller Freeman, 1993).

↑ - 5

Janet Ore, “Mobile Home Syndrome: Engineered Woods and the Making of a New Domestic Ecology in the Post–World War II Era,” Technology & Culture 52, no. 2 (2011): 261. Interestingly, focusing on a period well before World War II, Pamela Simpson also explores the democratizing impacts of material cheapening and fakery—not specifically with regard to access to home ownership but with access to ornamental products and other elements of home beautification. Pamela Simpson, Cheap, Quick, and Easy: Imitative Architectural Materials, 1870–1930 (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1999), esp. chap. 7, “Substitute Gimcrackery: Aesthetic Debates and Social Implications.”

↑ - 6

For a description of the issues at stake in pending Masonite cases, see a chapter authored by the lead plaintiff’s attorney in these cases: Elizabeth J. Cabraser, “Developments in Nationwide Non-Injury Products Liability Litigation,” in the American Law Institute–American Bar Association (ALI-ABA) Course of Study materials in Products Liability, Course Number CB16.

↑ - 7

Drew DeSilver, “Why Home Sidings Can’t Take the Damp,” Seattle Times, August 6, 2000.

↑ - 8

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Primary Causes of Indoor Air Problems: Pollutant Sources,” accessed July 2021, https://www.epa.gov/indoor-air-quality-iaq/introduction-indoor-air-quality#sources.

↑ - 9

See Ore, “Mobile Home Syndrome”; and Nicholas Shapiro, “Attuning to the Chemosphere: Domestic Formaldehyde, Bodily Reasoning, and the Chemical Sublime,” Cultural Anthropology 30, no. 3 (2015): 368–93.

↑ - 10

Janet Ore, “Workers’ Bodies and Plywood Production: The Pathological Power of a Hybrid Material,” Aggregate 10 (June 2022), https://doi.org/10.53965/CPGG8794.

↑ - 11

This could also be framed through the lens of critical discard studies: easy obsolescence, planned or not, positions the home within a broader network of waste production, whether these practices are explicitly named as waste-making or not. See Max Liboiron and Josh Lepawsky, Discard Studies: Wasting, Systems, and Power (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2022). See also the collaboratively produced discard studies web resource: https://discardstudies.com/.

↑ - 12

Pamila Gupta and Gabrielle Hecht, “Toxicity, Waste, Detritus: An Introduction,” Science, Medicine, and Anthropology, October 10, 2017, http://somatosphere.net/2017/toxicity-waste-detritus-an-introduction.html/. For an early introduction to the idea of slow violence and environmental degradation, see Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013).

↑ - 13

For social and environmental histories of the American single-family home, see Gwendolyn Wright, Moralism and the Model Home: Domestic Architecture and Cultural Conflict in Chicago, 1873–1913 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980); Gwendolyn Wright, Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America (New York: Pantheon Books, 1981); Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Lisa Goff, Shantytown, USA: Forgotten Landscapes of the Working Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); Gail Radford, Modern Housing for America: Policy Struggles in the New Deal Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996); Gilbert Herbert, The Dream of the Factory-Made House: Walter Gropius and Konrad Wachsmann (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984); Hyun-Tae Jung, “‘Technologically’ Modern: The Prefabricated House and the Wartime Experience of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill,” in Sanctioning Modernism: Architecture and the Making of Postwar Identities, ed. Vladimir Kulić, Timothy Parker, and Monica Penick (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014), 186–218; Adam Rome, The Bulldozer in the Countryside: Suburban Sprawl and the Rise of American Environmentalism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013); Dianne Harris, “Modeling Race and Class: Architectural Photography and the U.S. Gypsum Research Village, 1952–1955,” in Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, ed. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis, and Mabel Wilson (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 218–38; and Sonya Salamon and Katherine MacTavish, “The Mobile Home Industrial Complex,” in Singlewide: Chasing the American Dream in a Rural Trailer Park (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017), 13–40.

↑ - 14

Howard Frederick Weiss/Wood Conversion Company, “Utilizing Wood Waste,” US Patent 1,631,172, filed May 19, 1921, and issued June 1, 1927.

↑ - 15

Howard Frederick Weiss/Wood Conversion Company, “Utilizing Wood Waste.”

↑ - 16

Howard Frederick Weiss/Wood Conversion Company, “Utilizing Wood Waste.”

↑ - 17

In 1938, the Forest Products Laboratory offered the following description of the aims of utilization and conversion research: “Research must aid in solving many difficult problems—how to utilize more efficiently the small-sized and second-growth trees which will form the bulk of our future forests; how to secure useful service from the many wood species that are now used little if at all; how to turn to economic account the large wastes that occur in the conversion of trees into commodities; how to secure greater service and economy from wood through selection of material, control and modification of its properties, improvement of treating processes, and the development of new and better methods of wood fabrication and conversion.” The Forest Products Laboratory: A Brief Account of Its Work and Aims, USFS/USDA Misc. Publication No. 308 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1938), 4. For a broader overview of how frameworks of valuation and quantification of natural systems and services have changed over the past century, see James Igoe, “A Genealogy of Exchangeable Nature,” in The Carbon Fix: Forest Carbon, Social Justice, and Environmental Governance, ed. Stephanie Paladino and Shirley J. Fiske (New York: Routledge, 2016), 25–35. See also Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, “Natural Universals and the Global Scale,” in Friction: An Ethnography of Global Connections (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005), 89–120.

↑ - 18

University of Minnesota Historical Society, Finding Aid for Conwed Corporation Records, accessed March 10, 2022, http://www2.mnhs.org/library/findaids/00477.xml. The Wood Conversion Company changed its name to the Conwed Corporation in 1967.

↑ - 19

For the 1925 patent, see William H. Mason/Masonite Corporation, “Process of Making Paper Pulp,” US Patent 1,872,996; filed May 21, 1925, and issued August 23, 1932. Quoted text from William H. Mason/Masonite Corporation, “Water Resistant Fiber Product and Process of Manufacture,” US Patent 1,784,993; filed May 12, 1928, and issued December 16, 1930.

↑ - 20

William H. Mason/Masonite Corporation, “Hard Grainless Fiber Product,” US Patent 1,789,825; filed June 13, 1928, and issued January 20, 1931.

↑ - 21

Emily Brock, Money Trees: The Douglas Fir and American Forestry, 1900–1944 (Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2015).

↑ - 22

See, for example, Roosevelt’s description in Theodore Roosevelt, “The Forest in the Life of a Nation,” in Proceedings of the American Forest Congress Held at Washington D.C., January 2 to 6, 1905, under the auspices of the American Forestry Association (Washington, DC: H. M. Suter, 1905), 10–11.

↑ - 23

US Bureau of Standards, Simplified Practice: What It Is and What It Offers; Summary of Activities of the Division of Simplified Practice and Description of Services Offered to American Industries (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1924).

↑ - 24

US Bureau of Standards, Simplified Practice, 5–6. One of the three pillars of simplification, according to this Bureau of Standards document, was specification. For several decades during this period, as Michael Osman argues, the practice of architecture had been undergoing a similar turn toward simplification, manifesting in changes in office organization and more specialized architectural labor; see Michael Osman, Modernism’s Visible Hand: Architecture and Regulation in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), 174, 177. In relation to how practices of simplification via specification operated relative to the lightweight wooden (platform) frame, see also Michael Osman, “Specifying: The Generality of Clerical Labor,” in Design Technics: Archaeologies of Architectural Practice, ed. Zeynip Çelik and John May (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 129–62.

↑ - 25

William Greeley, “The Problem of Timber Waste,” in Report of the National Conference on Utilization of Forest Products, USDA Miscellaneous Circular No. 39 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1925), 9.

↑ - 26

John Gries, “Better Utilization of Lumber in Buildings,” in Report of the National Conference on Utilization of Forest Products, USDA Miscellaneous Circular No. 39 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1925), 56.

↑ - 27

For a fair-wide examination of the use of Masonite in many applications, see Lisa D. Schrenk, Building a Century of Progress: The Architecture of Chicago’s 1933–1934 World’s Fair (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007), 135–36. See also “Masonite: A Souvenir of the 1934 World’s Fair,” fair literature created by the Masonite Corporation, Chicago, IL, ca. 1934, digitized by the Building Technology Heritage Library and the Association for Preservation Technology International, https://archive.org/details/MasoniteASouvenierOfThe1934WorldsFair.

↑ - 28

Archibald MacLeish and Fortune Magazine, Housing America (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1932), 111. For an overview of 1930s low-cost house competitions, see Andrew Shanken, “Architectural Competitions and Bureaucracy, 1934–1945,” Architectural Research Quarterly 3, no. 1 (1999): 43–56, published online August 19, 2008, https://doi.org/10.1017/S1359135500001743.

↑ - 29

Albert Farwell Bemis and John Burchard, The Evolving House: Volume II, The Economics of Shelter (Cambridge, MA: Technology Press/Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1934), 495.

↑ - 30

Jung, “‘Technologically’ Modern,” 191–96. See also Alfred Bruce and Harold Sandbank, A History of Prefabrication (Raritan, NJ: John B. Pierce Foundation, Housing Research Division, 1945).

↑ - 31

“Month in Building,” Architectural Forum 69 (August 1938): 4. The prefabrication of houses would continue to be studied under the auspices of the Bemis Foundation, operating in conjunction with MIT.

↑ - 32

A statement from Bemis’s second volume of the Evolving House series is also illuminating: “A solution much better suited to our economic principles would be that the housing industry develop modern efficiency within itself. Better housing throughout the country is economically possible and socially urgent, but it is to be accomplished through industrial and engineering efforts rather than by government intervention. The technical skill of our time can most certainly cope with this problem; and engineering is the turbine that can transform the wildly wasteful rapids of social forces into useful power.” Bemis and Burchard, Evolving House, 2:495 (emphasis added). Historian Gwendolyn Wright has traced this preoccupation with engineering one’s way out of a problem through the postwar period, noting the many historical examples in which architects, engineers, and bureaucrats throughout US history have demonstrated an unfailing belief in the possibility for “dramatic technological solutions for complex housing problems.” Wright, Building the Dream, 244.

↑ - 33

Burnham Kelly and the Albert Farwell Bemis Foundation, The Prefabrication of Houses (New York: John Wiley and Sons, Inc., and the Technology Press of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1951), 24.

↑ - 34

MacLeish and Fortune Magazine, Housing America, proofs for advertising of General Houses scheme, between pages 120 and 121, with the following description: “‘K’ refers to the basic housing type; ‘2’ indicates a subdivision of that type. ‘H’ expresses entrance through a hall. ‘4’ means that there is space for four beds in two bedrooms. ‘O’ stands for an optional extra room.”

↑ - 35

See Timothy Mennel, “‘Miracle House Hoop-La’: Corporate Rhetoric and the Construction of the Postwar American House,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 64, no. 3 (2005): 340–61; Joseph J. Corn, Imagining Tomorrow: History, Technology, and the American Future (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986). For a close look at the construction of the notion of the postwar home through architectural photography, see Harris, “Modeling Race and Class.”

↑ - 36

Masonite Corporation, “Masonite Products in a Century of Progress,” promotional literature, ca. 1933, Century of Progress International Exposition Publications, Crerar Ms 226, Hanna Holborn Gray Special Collections Research Center, University of Chicago Library, https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/ead/pdf/century0074.pdf.

↑ - 37

Masonite Corporation, advertisement for Masonite Presdwoods, Better Homes and Gardens, March 1943, 52.

↑ - 38

Masonite Corporation, “How to Repair, Remodel, Build on the farm with Masonite Presdwood … the wonderwood of 1000 uses,” promotional literature, ca. mid-1930s, Building Technology Heritage Library online archive, https://archive.org/details/MasoniteHowtoRepairRemodelBuildFarm0001.

↑ - 39

Catherine Bauer Wurster noted that many of the projects in MoMA’s 1932 International style show exhibited what she called a “technocratic symbolism—that is an architecture that (above all else …) appeared to have embraced new building methods and materials without actually being quite ready to do so.” Catherine Bauer Wurster, “The Social Front of Modern Architecture in the 1930s,” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 24, no. 1 (1965): 50. For a more sustained examination of the rhetoric of material purity and richness that often infused descriptions of these materials, see Erin S. Putalik, “Pure Trash: New Woods and Old Claims in Architectural Materiality,” Architectural Theory Review 25, no. 1–2 (2021): 64–80, https://doi.org/10.1080/13264826.2021.1946574.

↑ - 40

“Home & Field Presents The Masonite House at A Century of Progress International Exposition,” Home & Field, July 1933, n.p.

↑ - 41

For a discussion of the range of utilitarian uses that Masonite found in later decades, see Carol Gould, “Masonite: Versatile Modern Material for Baths, Basements, Bus Stations, and Beyond,” in APT Bulletin: The Journal of Preservation Technology 28, no. 2–3 (1997): 64–70.

↑ - 42

I discuss Raymond’s plywood house in Erin Putalik, “Endless Lamellae and Finer Grains: A Brief History of Better Wood,” in Blank: Speculations on CLT, ed. Jennifer Bonner and Hanif Kara (London: AR&D, 2021). See also Nancy Gruskin, “Building Context: The Personal and Professional Life of Eleanor Raymond, Architect—1887–1989” (PhD diss., Boston University, 1998); and Doris Cole, Eleanor Raymond, Architect (Philadelphia: Art Alliance Press, 1981). For the plywood house, see Erin Putalik, “Eleanor Raymond’s Peabody (1940) and Parker (1941/6) Plywood Houses,” which is chapter 7 in Erin Putalik, “Nature, Better: Reconstituting Wood in American Architecture, 1927–1941” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2020). For the solar house (the Dover Sun House), see Daniel A. Barber, A House in the Sun: Modern Architecture and Solar Energy in the Cold War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 129–41.

↑ - 43

Doris Cole, Eleanor Raymond: Architectural Projects, 1919–1973 (Boston: Institute of Contemporary Art, 1981), n.p., exhibition catalog published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same title presented at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, September 15–November 1, 1981.

↑ - 44

Richa Wilson and Kathleen Snodgrass, Early 20th-Century Building Materials: Fiberboard and Plywood (Missoula, MT: US Department of Agriculture/US Forest Service, National Technology and Development Program, 2007); John M. Coates, Masonite Corporation: The First Fifty Years 1925/1975 (Chicago: Masonite Corporation, 1975), 4–42.

↑ - 45

John I. Zerbe, Zhiyong Cai, and George B. Harpole, “An Evolutionary History of Oriented Strandboard (OSB),” General Technical Report, FPL-GTR-236, USDA Forest Service, Forest Products Laboratory, 2015.

↑ - 46

As New York University professor of food studies Amy Bentley, quoted in a pithy history of the bologna sandwich, has stated, the iconic meat product has “been inserted into the national psyche of despicable foods, laughable foods.” Quoted in Amy McKeever, “How Lunch Became a Pile of Bologna: The Story of a Sandwich Staple Many People Love to Hate,” Eater.com, December 2, 2016, https://www.eater.com/2016/12/2/13799660/bologna-sandwich-recipe-history.

↑ - 47

Quoted text from William H. Mason/Masonite Corporation, “Water Resistant Fiber Product and Process of Manufacture,” US Patent 1,784,993.William H. Mason and Masonite received numerous patents in the 1920s for the use of organic fiber in building materials.

↑ - 48

DeSilver, “Why Home Sidings Can’t Take the Damp.”

↑ - 49

June Fletcher, “When Dream Products Turn into Nightmares: Is Your House a ‘Composite’? Will the Stuff Fall Apart? What to Do If It Does,” Wall Street Journal, July 24, 1998.

↑ - 50

Fletcher, “When Dream Products Turn into Nightmares.”

↑ - 51

DeSilver, “Why Home Sidings Can’t Take the Damp.”

↑ - 52

Alabama Judicial Data Center, Circuit Civil Court of Mobile County, Alabama, “Class Action Summary, Circuit Civil,” CV 94 004033 00, digitized copy acquired from Circuit Court of Mobile, Alabama, March 2022. It should be noted that this motion to certify a set of suits as a class action failed in at least one other location; the US District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana (on February 19, 1997) released its decision to deny class status to a set of plaintiffs. One of the reasons stated in the case summary was that “there is no single Masonite manufacturing process or Masonite product, so even questions of product character and manufacturer appear inappropriate for class-wide resolution… . Masonite makes siding at three different plants, using different woods, additives, equipment, and processes.” Even though the plaintiffs’ expert witness on building science stated that Masonite was a generic product regardless of the original raw material used, the differing wood species used by different plants was one of the reasons this second attempt at a broader class certification was dismissed. US District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, Civil Action MDL NO. 1098 Section “F”; “In re Masonite Corp. Hardboard Siding Prods. Liab. Litig.,” 170 F.R.D. 417. This is interesting relative to the original patent language for Masonite, which showed clear enthusiasm for the range of fibrous organic material that might be used with the Masonite process in order to produce the sheet products.

↑ - 53

Jonathan Welsh, “Suit against Unit of International Paper Goes to Jury,” Wall Street Journal, September 13, 1996.

↑ - 54

Elizabeth J. Cabraser, “Civil Practice and Litigation Techniques in Federal and State Courts Volume 2.” ALI-ABA (American Law Institute-American Bar Association) Course of Study Materials, 2004, https://advance.lexis.com/api/document?collection=analytical-materials&id=urn:contentItem:4BYR-V6J0-00CP-049Y-00000-00&context=1516831.

↑ - 55

Second amended Class Action Complaint: July 3, 1996, Mobile County District Civil Court.

↑ - 56

Jonathan Welsh, “International Paper Settles Suit on Masonite Siding,” Wall Street Journal, July 15, 1997.

↑ - 57

Lieff Cabraser Heimann & Bernstein, Attorneys at Law (plaintiffs’ co-lead attorney), Defective Products Division, Masonite Hardboard Siding, accessed April 15, 2023, https://www.lieffcabraser.com/defect/masonite/.

↑ - 58

Letter from “B” [name removed to preserve plaintiff’s privacy] to the Independent Claims Administrator assigned to the Masonite Hardboard Siding Settlement; copy to Judy Naef, et al., Plaintiffs, Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama, Re: Civil Action No. CV-94-4033, dated July 6, 2000.

↑ - 59

Plaintiffs’ Opposition to Defendants Motion for Judgment: November 18, 1996, Mobile County District Civil Court.

↑ - 60

The damage for which plaintiffs were to be compensated was extremely specific and measurable in the amended settlement: “The eight tests are: (1) thickness swell of 0.604 [inch] for siding with a nominal thickness of inch, and 0.4 [inch] for siding with a nominal thickness of 7/16 inch; (2) edge checking, where a feeler gauge of .025 inch thickness and one half inch width can be inserted one-half inch into a suspected delaminated edge with moderate hand pressure; (3) fungal degradation; (4) buckling in excess of one-quarter inch between studs spaced not more than 18 inches on center; (5) wax bleed, raised or popped fibers or fiber bundles, where the condition exists on more than 25% of the board’s surface and, in the case of wax bleed, where the siding was painted within four years of the date of inspection; (6) delaminated or cracked primer or primer peel or peeling, blistering, or cracking of the original finish; (7) surface welting, or swelling around nail heads; or (8) for panel siding where the edge is not visible, sponginess and/or moisture content above 20% using a Delmhorst Moisture Meter.” From Final Settlement Approval: Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law, Circuit Court of Mobile County, Alabama, filed January 23, 1998.

↑ - 61

Plaintiffs’ Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for Judgment, 1996, citing Gideon v. Johns-Manville Sales Corp., 761 F.2d 1129 (5th Cir. 1985).

↑ - 62

Plaintiffs’ Opposition to Defendant’s Motion for Judgment, 1996.

↑ - 63

Cabraser, “Developments in Nationwide Non-Injury Products Liability Litigation.”

↑ - 64

Fletcher, “When Dream Products Turn into Nightmares.”

↑ - 65

See the introduction to this series for a review of many of these texts in the context of other accounts of living with chemical toxicity.

↑ - 66

Ore, “Mobile Home Syndrome,” 261–62.

↑ - 67

Shapiro, “Attuning to the Chemosphere,” 271.

↑ - 68

Soraya Boudia, Angela N. H. Creager, Scott Frickel, Emmanuel Henry, Nathalie Jas, Carsten Reinhardt, and Jody A. Roberts, “Residues: Rethinking Chemical Environments,” Engaging Science, Technology, and Society 4 (2018): 166.

↑ - 69

Gupta and Hecht, “Toxicity, Waste, Detritus.” Gupta and Hecht’s observation with regard to the waste and value—that “changes in value are never clear, unidirectional, or fixed in time and space”—is also accurate with regard to the history of waste-based wood materials.

↑ - 70

Meredith TenHoor and Jessica Varner, “Mattering Toxics and Making Toxics Matter in Architecture and Landscape Histories,” Aggregate 10 (June 2022), https://doi.org/10.53965/WADN3098.

↑ - 71

See the sources cited in notes 5 and 13.

↑ - 72

Masonite Corporation, “Three Hundred Money Making Opportunities for Contractors, Carpenters and Lumber Dealers: A Summary of Surprising New Uses for Masonite Products,” n.d., digitized by the Building Technology Heritage Library and the Association for Preservation Technology International, https://archive.org/details/MasoniteThreeHundredOps0001.

↑ - 73

It should be noted that no evidence was found that the manufacturer was aware of the speed of physical decay of the material prior to the lawsuits. One could speculate that this awareness emerged in concert with customer complaints in the decades leading up to the lawsuit, but no documentation of this was found in accessible archives.

↑