Unknowing Wastelands in Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum

Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum.

Photo by author.

Days. Almost every one we grab pickaxes. Almost every one we mine.

We hum worksongs. We sing hymns. We chip worry stone. We

hope. We gather moss. We lie flat. We scratch at the mineshaft.

We descend deeper. We lamp away from the light not toward

exit but through the broken core.

—Samiya Bashir

Let’s orient to the everyday labor and built environment of the African American artist-educator Noah Purifoy and his desert-floor collaborators in Joshua Tree, California.1 In this essay, I offer a field trip with some suggestions for how to interpret Purifoy’s creative work as an antidisciplinary formation of blackness that can unknow the Mojave Desert as so-called “wasteland.” Some preparatory notes for this trip are helpful. First, by not capitalizing the word “blackness,” I am underlining it as a concept that, while connected to the social (and sociological) category of “Black,” is not foreclosed by it. Second, I use the term “antidisciplinary” following Katherine McKittrick’s assertion that “the work of discipline, so neatly and so quietly tied to the biocentric infrastructures of empire, forbids a genre of blackness that is not solely and absolutely defined by and through abjection, subjection, and objectification.”2 Purifoy’s blackness in and of the desert is too wonderful for that. Third, I seek to unknow “wasteland” because the Mojave has been historically read as such, signaling moral, cultural, and ecological deficits that have justified the accessing, extracting, and disposing of this Land.3 The word Land is capitalized here after Max Liboiron’s use of it as shorthand for the multiple enacting relations that make up particular lands, “as a proper name that is specific and unique, not universal and common.”4 Like the lowercased word land, “wasteland” obfuscates those vital relations. Fourth, it also sits close to a keyword in the Purifoy lexicon—“junk”—that has connected him to other twentieth-century avant-garde artists whose primary medium was worthless or wayward objects, while also associating his work with the de-industrializing Los Angeles neighborhood of Watts in the 1960s and 1970s.5 The proximity of desert wasteland to urban junk is not arbitrary, given that the former term “conjures up visions of wild and remote landscapes like deserts, mountains, steppes, and ice caps, and, at the very same time, derelict and abandoned landscapes like former military bases, boarded-up mines, and shuttered industrial plants.”6 Our trip reads against that proximity and its settler-capitalist logics by fathoming a blackness that does not metaphorize Black people and Black places with waste but instead conjugates through the relational outdoor-ness of the Mojave Desert region and flourishes underneath its toxic grounds.7 Informed by site visits that occurred between 2017 and 2021, as well as months I spent in my basement “away” from a pandemic, white nationalism, and wildfire smoke in eastern Washington State, the fathoming in the text that follows extends the sensibility of Samiya Bashir’s poetry (epigraph) and imagines how an excursion to and through desert blackness, via Purifoy’s place, can disengage from wasteland thinking and its colonial praxis.

62975 Blair Lane

We get ourselves to 62975 Blair Lane, Joshua Tree, CA 92252 and park in the shade. We wear covered shoes because of ants and bring water because it is otherwise scarce. Air quality and visibility are okay today, despite the large export of ozone, sulfur dioxide, and particulate matter migrant from Los Angeles.8 It is difficult to notice other anthropogenic impacts on the site, but things we know have harmed Southern California desert ecosystems include overgrazing by domestic livestock; the building of linear corridors for roadways, electricity infrastructure, and pipelines; off-road vehicle use; military training and testing sites; and mining. Special mention goes to the city of Palm Springs, whose twentieth-century history is replete with compulsory automobility and air-conditioned leisure pads. Unless you are local, walking around and towards Purifoy’s site —an activity that is itself an ecological stressor—precludes perceiving the cumulative damage: compacted and destabilized soils, erosion by wind and water, decreased species populations, hearing loss in animals, plant trampling, fragmented habitats, restricted gene flows, invasive species, fugitive dust, and toxic tailings.9 What we also cannot readily perceive is the “slow violence” that permeates and constitutes Land in California as a settler colonial network of Indigenous dispossession and racism against non-European migrants and their descendants.10 Toxicity abounds, in both material and social ways.

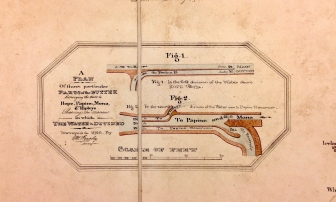

Fig. 1.

Photo by author.

Here we are in any case approaching a gateway framed with old rubber tires, each painted with a different letter to spell something like WELCOME, but with an extra L and W (fig. 1). Extra welcome. Free of charge, we walk through 10 acres of a flat, unfenced expanse featuring 120 large-scale art works known collectively as the Outdoor Desert Art Museum. The pieces are tended to by a small support staff and were fabricated from things found and assembled in the desert by the Alabama-born and Los Angeles refugee Noah Purifoy. In 1989, the seventy-two-year-old “junk” artist, educator, community organizer, social worker, and founding member of the California Arts Council was priced out of Los Angeles residency and accepted an invitation to relocate to a property, owned by his longtime friend Debby Brewer, that would eventually become the museum.11 As Purifoy quickly learned, there was not much junk in the area. With no public garbage collection days and a desert ethic of resell and reuse, few objects seemed “out of place” here, and the artist’s method of scavenging for discards—most notably debris from the Watts uprising in 1965—shifted to swap meets and local donations, where he obtained all manner of stuff.12 Working with worn clothes, bowling balls, broken appliances, aluminum siding, redwood shingles and lath, foam rubber, car and bicycle parts, fencing, burlap, bones, rocks, artificial grass, decorative recessed moldings, and more, Purifoy fabricated open-air buildings, urban infrastructure, gardens, graveyards, towers, and totems (figs. 2–7). He lived with these assemblages, initiating and bearing witness to their desert transformations until his death in 2004 on the site.

Fig. 2.

Photo by author.

Fig. 3.

Photo by author.

Fig. 4.

Photo by author.

Fig. 5.

Photo by author.

Fig. 6.

Photo by author.

Fig. 7.

Photo by author.

Not Nothing

Wasteland thinking is easy to come by in this Land. In their review of Desert X 2019, a public art biennial, critics Wendy Cheng and Juan De Lara unpack curatorial assumptions that the eastern Coachella Valley is a blank canvas—a blankness that registers in the perceived absence of contemporary art in the area by elite arts organizations. These assumptions operate in parallel with the touristic construction of the region as a place in which to do nothing but engage in low-key leisure.13 The desert = nothingness equation is also a common source of critique in ecological literature about the region.14 To approach the museum’s potentials, we bypass white colonial tropes of the western frontier that flow from such wasteland thinking. This is not easy. The site triggers New Jersey–based desert booster John C. Van Dyke’s 1901 observations from an Anglo outsider’s perspective that in the southwestern desert, settlement produces redemptive aesthetics: “Plain upon plain leads up and out to the horizon—far as the eye can see—in undulations of gray and gold; ridge upon ridge melts into the blue of the distant sky in the lines of lilac and purple; fold upon fold over the mesas the hot air drops its veiling of opal and topaz. Yes; it is the kingdom of sun-fire.”15 The site can get snared in John Steinbeck’s allegorical abstraction that the Mojave, “being an unwanted place, might well be the last stand of life against unlife.”16 Recently, the museum has been used as a backdrop for wedding engagement and fashion photography shoots that alternately evoke hipster homestead futures and fetishize stressed leather and oversized fringed fabrics.17 The museum also shares topography with unmapped high-end desert modern retreat-cum-panic rooms “suspended between earth and sky,” and it shares an area code with the nostalgic Pioneertown, built in the 1940s as a set for western b-films and still used for reenactments of gunfights and stampedes to entertain the public.18

Fig. 8.

Photo by author.

Purifoy was not estranged from these motifs, particularly the Old West nostalgia. The artist read pulp westerns as a young adult in Birmingham, Alabama, and his final work in Joshua Tree, Gallows (2003), involved building a bright white wooden scaffolding modeled after the centerpiece of the 1968 film Hang ‘Em High (fig. 8).19 But his was an ambivalent settlement in thorny relation to its cultural forms and subjectivities. Historically speaking, African American migrants to stolen Indigenous Lands in the U.S. West were also familiar with systems of dispossession through slavery.20 For Saidiya Hartman, settlement itself, as a practice of owning things, land, and people, has been a point of racial disassociation:

To be white was to own the earth forever and ever. It defined who they were and what they valued; it shaped their vision of the future. But black folks had been owned, and being an object of property, they were radically disenchanted with the idea of property. If their past taught them anything, it was that the attempt to own life destroyed it, brutalized the earth, and ran roughshod over everything on God’s creation for a dollar.21

And so, fellow fathomers, we begin to notice other frontier histories and their disenchantments in Purifoy’s work: the crumbling plaster of Spanish Arches (2000), the spare wire-branch-rag structures of Indian Burial Ground I and II (1991), and the plywood and plastic corner molding that make up Earthquake – Los Angeles 1994 (1994). As an entropic ensemble of ever-eroding states of matter, this scorched and open place plays the long game of blackness, which “by its very negation in the category of nonbeing within economics of Whiteness lives differently in the earth.”22 Reading Édouard Glissant, Dionne Brand, and Saidiya Hartman, Kathryn Yusoff posits this long living as the history of blackness itself, apart from and disruptive to the epistemologies of colonialism and trans-Atlantic slavery and the racializations therein that divided the world into human and thing, subject and matter, active and inert.23 How might this blackness that lives differently in the earth spatialize in the desert? How might it, in style and substance, connect with the polyphonic soliloquies and myriad materialities of Purifoy’s desert finds; the site’s bedrock, soils, and sand; its creosote bush scrub, sagebrushes, and yuccas; its local wildlife; the Serrano, Cahuilla, and Chemehuevi peoples; the chronically ill and the poor, each forming outlaw relations that re-world in and around their uneven finitude?24 In what ways has this built environment initiated these very relations, from the mangled creosote branches and corrugated metal scrap of the geographically displaced Igloo (1992) to the bee colony occupying the hulls of Untitled (Catamarans) (1997) to Purifoy’s vibing with those desert critters who, like him, were visible from long distances but “all run quiet”?25 (figs. 9–10). And how do these relations eschew, make strange, or mend the desert’s settler-capitalist–designated identity as wasted/ing space?

Fig. 9.

Photo by author.

Fig. 10.

Photo by author.

“I feel sad,” says a young white woman on her way out of the museum. By way of explanation, she rehearses the story of Purifoy as a Black artist and arts worker depleted by the artworld of Los Angeles and discharged to its desolate edge. Heads nod in agreement. For a moment, the museum becomes a pedagogy of professional withering, compounded by multiple signs of Black social death (per Gallows), by Purifoy’s physical death, and by the area’s unremitting temperatures, dryness, elevation, and apparent absence of living ecosystems.26 As McKittrick notes, “In terms of geography, our [Black] sense of place is often pre conceptualized as dead and dying and this lifelessness extends outward, from that death and deadliness, toward extinction.”27 Despite this preconceptualization, the possibility that Purifoy’s practice could have been intermittently intra-active and life giving/receiving remains, radiates, and refracts normative expectations of Black expression.28 Here hums an out-of-doors museum episodically down and out from the logics of property and its personhood, “where scorned flesh and scorned earth commune in scandalous arrangement” and do not await corrective outcomes that would recuperate some desert dwellers into models of good (read: re-productive) life in the badlands.29 Purifoy’s practice, still active after his death, is indifferent to those scenarios, as intimated in the artist’s preface to his own posthumously published site tour text: “no matter what option a viewer chooses to take, it is our desire that each of you get so close to the piece that your see the smoke from its breath as it comes alive.”30

Underground

We circle back, forestalling the negations of colonialism, slavery, and feeling sad on site in an effort to know in another way these arid ten acres and their assemblages of life and nonlife.31 Again, the welcome gateway does its work, this time with an accent on what Christina Sharpe calls “anagrammatical blackness”—that is, blackness as a pattern of rearranging and being rearranged into new formations, as in the rearrangement of letters to form a new word, phrase, or name: “blackness anew, blackness as a/temporal, in and out of place and time putting pressure on meaning and that against which meaning is made” (fig. 11).32 WE/ME WLL COME … CLEW WE/ME LOW.

Fig. 11.

Photo by author.

Adjacent to the gateway is what some visitors take as another: 63030 Blair Lane (1995), a row of metal public restroom toilet paper dispensers–cum–rural mailboxes mounted on wooden poles, which once concluded with a toilet-seat-cover dispenser.33 Sooner rather than later, we encounter the many easily obtainable toilets from this desert recycling community that shift our awareness to lower places. Purifoy was well attuned to the toilet’s downward pitch, having used a fetid one in his 1971 exhibit at the Brockman Gallery in Los Angeles to construct a squalid apartment as “the very essence of poverty and the way black people live.”34 In Joshua Tree, Purifoy’s toilet works exchange abject pessimism for visual puns, as in, for example, Voting Booth (1998), in which an electoral space does double duty as an outhouse, and White/Colored (2000), which restages a site of Jim Crow segregation with a drinking fountain for whites and a filthy toilet bowl for Blacks (figs. 12–14).

Fig. 12.

Photo by author.

Fig. 13.

Photo by author.

Fig. 14.

Photo by author.

When it comes to approaching larger works, figurative shit slides into formalist defilement. Stepping into The White House (1990–93), we enter a colossal, oval-shaped white wooden structure (twenty by thirty by forty-five feet) with two levels and a central tower.35 Tanks and bowls stand in open-air, stall-like arrangements, seats and lids are mounted on steep inclines, and the entrance features a short columnar archway that recalls—then rescinds—the purifying forms of modernist sculptor Constantin Brâncuşi (figs. 15–17). Purifoy and his special medium truncate the slender and soaring trapezoidal clarity expressed most vividly in Brâncuşi’s Endless Column variation by incorporating and repeating the toilet bowl shape with a thick rim, only to cap the columns with three broad tanks.36 There is no high point in this high desert.

Fig. 15.

Photo by author.

Fig. 16.

Photo by author.

Fig. 17.

Photo by author.

On facing the most prominent form, Sage at Sage (Collage) (1996–97), we continue our descent. Extending ten feet across and twelve feet up from a flat assemblage, these fifteen toilet bowls were initially stacked in 1996–97 and then repositioned by caretakers in 2016 after they fell over (fig. 18).37 Together, they assert a white porcelain presence that is both evocative of intestines and an amplification of the foiled Brâncuşi-eque gesture in The White House. As intestines, they twist and turn, following the experience of digestive distress through a sequence of baroque contortions. As columns run amuck, the asymmetrical piling of the toilets creates precarity. Their sideways placement dissolves trapezoids into a serpentine maze. The structures’ supporting cables take the soaring winds out of the entire edifice (fig. 19). So too do the sand- and shell-filled bowls at the sculpture’s base, likely placed by visitors or vandals, and a property ownership sign placed sometime in 2017 that functioned as an impromptu museum label covered in rust and more jokes: “RIGHT TO PASS / BY PERMISSION / SUBJECT TO CONTROL OF OWNER / SEC. 1008 CIVIL CODE / NO DUMPING” (fig. 20). Toilet humor that spans the symbolic and the formal thus teases investments in the Land as a space of solemnity and spiritual transcendence. It reorganizes the Mojave’s wasteland conventions of clean, spare lines for clean, spare living through jaunty and intricate shitscapes calibrated to who and what underwrites that simplicity.38

Fig. 18.

Photo by author.

Fig. 19.

Photo by author.

Fig. 20.

Photo by author.

Please note: there are no restroom facilities on the museum’s site, and the small municipality of Joshua Tree has no central sewer system. Also note: like land use and waste management, water use in the Mojave Desert is an unfolding challenge. Recent water-mining projects by a natural resource company called Cadiz, Inc., are a prominent case in point. To supply new developments in Southern California, Cadiz initially proposed to drain a fragile seven-hundred-square-mile aquifer through old railway pipes. The proposal failed. Now the company is seeking to push groundwater through a defunct oil and gas pipeline that crosses public lands. While some activists are concerned about this groundwater’s potentially dangerous levels of hexavalent chromium, a compound that occurs naturally in certain rocks and soils and is toxic to humans, groundwater in the Mojave region as a whole connects to freshwater springs and riparian vegetation that feed desert fauna and serve as “underground spiritual highways” for Indigenous peoples.39

In Richard Wright’s novel The Man Who Lived Underground, written in the early 1940s, a Black man comes across another spiritual highway, as it were, of indeterminate substances. Escaping from police entrapment and torture, Fred Daniels, wishing “he were a tiny insect that could crawl into one of those crevices in the brick wall,” lowers himself instead through a utility access hole and into the channels of the city sewer. There in the “watery blackness of the underground,” a place of “seeing with his fingers,” he finds new knowledge, capacities for self-determination, and an aversion toward the “obscene sunshine” on the street overhead.40 As Malcolm Wright has observed, “This experience in the underground is one of exile, of radical exile. It’s difficult, but it’s also freeing. And [Daniels] is for the first time [able] to think his own thoughts and be a human being outside of the racist paradigm, outside of the classist paradigm, outside of every paradigm that ruled his life up until that point.”41 Both outside and/as underground, Daniels ekes out a living space in a dream-like room wall-papered with green money, ornamented with the gold of suspended rings and watches, and shimmering with a dirt floor of diamonds—all stolen from the world above and transformed into a dexterous and vibrant vantage point from which to know it as “this vast, dreary spectacle.”42 Daniels’s sewer space-making suggests that Purifoy’s mad use of toilets on the desert floor is as much cartographics as pragmatics, egging us on to notice the promise of what circulates and can happen thereunder.

The lowest point in the museum is part of Earth Piece (1999), a work Purifoy planned while still living in Los Angeles and for which he saved a decade’s worth of funds to pay for construction equipment to assemble it (fig. 21).43 To prevent visitors from entering the now slowly eroding structure, caretakers have roped off its twenty-foot-deep U-shaped dirt trench. Rusted fencing, some weathered beams, signage, and a broken central bridge block any other pedestrian openings (figs. 22–23). By peering down, we catch glimpses of dense configurations of appropriated plastic, wood, plaster, and wire connecting the underground space of Earth Piece with another literary space. The basement in Ralph Ellison’s The Invisible Man is illuminated by the siphoned power of 1,369 lightbulbs: “Mine is a warm hole. And remember, a bear retires to his hole for the winter and lives until spring… . I am neither dead nor in a state of suspended animation. Call me Jack-the-Bear, for I am in a state of hibernation.”44 Referencing Duke Ellington’s 1940 jazz recording “Jack the Bear,” Ellison’s basement protagonist anticipates the ingenuity and refuge of Purifoy’s trench, which is also consonant with animal shelter. A warm bear hole in Harlem translates to something akin to a cool burrow for the desert tortoise in the hot and dry Mojave. With its digging powers, the species makes cooler and more humid spaces in which to spend the winters. Summer can also find tortoises hibernating, slowing down heart rates, breathing, digestion, and excretion to minimize water loss and maximize their chances of survival. If the creature is awake, travel outside the burrow is confined to early morning and early evening, which offers the added protection of shrub shade from predators.

Fig. 21.

Photo by author.

Fig. 22.

Photo by author.

Fig. 23.

Photo by author.

Such activity is captured in a photograph that Purifoy included in his 1997 guidebook about the site. Amid 104 other images of assemblage works, a lone desert tortoise moves across the sand and in the direction of a triangular shadow, possibly cast by one of Earth Piece’s aboveground plywood-and-plaster geometries that flank the trench, most likely at dawn or dusk. The caption reads,

“TURTLE” - DESERT WILD-LIFE. IT IS A RARE OCCASION TO SEE A

TURTLELIVE TURTLE IN THE HI DESERT, PARTICULARLY IN MY NECK-OF-THE WOODS. SO MY PHOTOGRAPHER FRIEND TOOK THIS PHOTOGRAPH. SHE SAID NO ONE WOULD BELIEVE HER OTHERWISE, AND OF COURSE SHE WAS RIGHT.45

Purifoy’s trench and singular wildlife snapshot shuttles us to historical practices of concealment and exposure where life was not federally protected.46 In the nineteenth century, the use of photography in and around the Underground Railroad belied the medium’s normative discourse of “light writing.” African Americans engaged in the project of self-emancipation understood photography as a tool that, in the wrong hands, could do harm to their clandestine work by identifying fugitive slaves to law enforcement and owners.47 Pondering the redolent darkness of a photograph from Dawoud Bey’s contemporary series on the railroad, Night Coming Tenderly, Black, Leigh Raiford similarly observes how photography habitually concretizes progress narratives of darkness into light and how Bey’s work suspends that impulse, rendering instead the space of the underground as one between fear and freedom:

A landscape image practically too dark to reproduce, that requires our “acute motion” to become legible (Dyson), that invites our slowed breath and listening ear to register their quiet (Campt), that references the terror of the hold and also the grace of being held (Sharpe), that enacts the tactics and strategies of dark sousveillance (Browne), that shifts our perspective from the seen to the seeing.48

In its lack of access and fragility, Purifoy’s trenchancy reverberates with a landscape photograph that stages bare visibility and high risk and yet also opens out to a place of possibility vis-à-vis those same qualities. Earth Piece digs into a sandy subterranean blackness that trades literal and figurative representation for, in Fred Moten’s formulation, “a mode of sensuous theoretical practice” amid the “predatory and incorporative worldliness” to which visual regimes are tethered. Moten’s keyword entry for “blackness” theorizes the valences of that practice, lamping us farther away from the light. It is “that autonomous song and dance [that] is our intellectual descent; it neither opposes nor follows from dissent but, rather, gives it a chance. Consent to that submergence is terrible and beautiful.”49

For the remaining time, we wander on our own, mindful of who feels free to do so and whose wanderings are legible as such.50 More commonly, we strain in the rising heat and glare, chewing on something Purifoy once said to a visiting journalist when standing over yet another hole in the ground with a rickety structure built over it: “That’s the way we do it [pointing down]. That’s the way they do it [pointing up].”51 The long game of desert blackness, as it happens, is a largely invisible game, played—beautifully—below the Mojave’s toxic grounds and through those nonhumanist relations that weather them. Enjoy the rest of your visit and please donate to the Noah Purifoy Foundation on your way out: https://www.noahpurifoy.com/donate.

My thanks to Michael B. Gillespie, Courtney R. Baker, Joshua Slepin, Matt Reynolds, Lyman Persico, and interlocutors at Whitman College, California College of the Arts, ASAP/10, the University of Rochester, Aggregate, and the Noah Purifoy Foundation.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Lisa Uddin, “Unknowing Wastelands in Noah Purifoy’s Desert Art Museum,” Aggregate 10 (June 2022), https://doi.org/10.53965/KJEZ9422.

- 1

Epigraph: Samiya Bashir, “Carnot Cycle,” Field Theories (New York: Nightboat Books, 2017), 14.

↑ - 2

Katherine McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 45–46.

↑ - 3

For a brief account of the Mojave Desert as wasteland, see the PBS documentary by Anna Rau and Corbett Jones, dirs., Tending Nature, Native American Land Conservancy, March 2020, https://www.nativeamericanland.org/post/tending-nature-pbs-documentary. For a cultural history of wasteland as a project of the British Enlightenment, see Vittoria Di Palma, Wasteland: A History (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014).

↑ - 4

Max Liboiron, Pollution Is Colonialism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021), 45–46.

↑ - 5

Lisa Uddin, “And Thus Not Glowing Brightly: Noah Purifoy’s Junk Modernism,” in Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, ed. Irene Cheng, Charles L. Davis II, and Mabel O. Wilson (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2020), 308–23; Yael Lipschutz, “66 Signs of Neon and the Transformative Art of Noah Purifoy,” in L.A. Object & David Hammons Body Prints, ed. Connie Rogers Tilton and Lindsay Charlwood (New York: Tilton Gallery, 2011); Kellie Jones, South of Pico: African American Artists in Los Angeles in the 1960s and 1970s (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

↑ - 6

Di Palma, Wasteland, 3.

↑ - 7

On the dangers of using (de-materialized) metaphors more broadly to describe black geographies, see McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories, 11.

↑ - 8

For example, when offshore winds bring in air pollutants from the Los Angeles Basin, the desert air’s ozone levels can exceed 100 parts per billion or more, as compared to 20 to 40 parts per billion in more remote areas. Jeffrey E. Lovich and David Bainbridge, “Anthropogenic Degradation of the Southern California Desert Ecosystem and Prospects for Natural Recovery and Restoration,” Environmental Management 24, no. 3 (1999): 317.

↑ - 9

Lovich and Bainbridge, “Anthropogenic Degradation,” 309–26; “John Gerrard on Western Flag and Our Shared Petro-history” (podcast), Desert X, accessed July 25, 2021, https://desertx.org/learn/podcast/desert-x-2019-podcast.

↑ - 10

The term “slow violence” comes from Rob Nixon, who argues that the gradual pace of environmental harm is “out of sight” and disproportionately shouldered by communities of color and the global poor. Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011). For an argument on how the “slow violence” of petrochemical infrastructure is best addressed by recognizing its entanglements with structural violence—and how those who endure the latter can “see” toxicity in ways that others miss when slow violence is understood as invisible, see Thom Davies, “Slow Violence and Toxic Geographies: ‘Out of Sight’ to Whom?,” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space April 2019, https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419841063. Written histories of navigating the dynamics of white supremacy in California are too numerous to list in full here. Two notable sources are Damon B. Akins and William J. Bauer Jr., We Are the Land: A History of Native California (Oakland: University of California Press, 2021); and Tomás Almaguer, Racial Fault Lines: The Historical Origins of White Supremacy in California (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1994).

↑ - 11

Purifoy’s fifteen years in Joshua Tree were spent without any financial backing, and for the first ten years he was without any assistants. Joe Lewis, “Noah Purifoy, An Introduction,” in Noah Purifoy: High Desert Assemblage Artist: Essays (Göttingen: Steidl Books and the Noah Purifoy Foundation, 2015), 4.

↑ - 12

“African-American Artists of Los Angeles: Noah Purifoy, Interviewed by Karen Anne Mason,” 1992 (transcript), 165, Oral History Program, Collection 300/383, Center for Oral History Research, Library Special Collections, University of California, Los Angeles; Lipschutz, “66 Signs of Neon,” 44. Liboiron has argued that scholarly descriptions of waste as “matter out of place” tend to conflate disposable objects and substances with things that systems of power reject, abject, and oppress, which can “inadvertently reinscribe the very power relations we are arguing against.” Max Liboiron, “Waste Is Not ‘Matter Out of Place,’” Discard Studies, September 9, 2019, https://discardstudies.com/2019/09/09/waste-is-not-matter-out-of-place/.

↑ - 13

Wendy Cheng and Juan De Lara, “Desert X 2019: Settler Colonial Imaginaries of the Desert,” American Quarterly 71, no. 4 (2019): 1077–91.

↑ - 14

For example: “A desert playa appears devoid of life. The halophytic saltbush community abruptly ends at the shoreline, and the cracked, rock-hard sediments do not resemble a fragile, structured soil. Consequently, many playas are designated as ‘open’ to OHVs [off-highway vehicles] because impacts to biological resources are not apparent.” Bruce M. Pavlik, The California Deserts: An Ecological Rediscovery (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 262.

↑ - 15

John C. Van Dyke, The Desert (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1901), 56.

↑ - 16

John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America (New York: Vintage Press, 1962), 192.

↑ - 17

Engagement and wedding photography found at Ash Durham Photography, accessed March 3, 2019, https://ashdurham.com/noah-purifoy-outdoor-art-museum-engagement-session/; and Junebug Weddings, accessed March 3, 2019, https://junebugweddings.com/wedding-blog/uniquely-artistic-california-elopement-at-noah-purifoy-outdoor-art-museum/. Fashion photography found in New York Times Magazine, October 30, 2016.

↑ - 18

Casa Plutonia, accessed August 1, 2021, https://www.casaplutonia.com/about, and https://pioneertownsun.com/pioneertown-visitors-information/ (no longer accessible).

↑ - 19

Yael Lipschutz, “A NeoHooDoo Western: Noah Purifoy, Spirit Flash, Art, and the Desert,” in Noah Purifoy: Junk Dada, ed. Franklin Sirmans and Yael Lipschutz (New York: Presetl, 2015), 56–57.

↑ - 20

Tiya Miles, “Beyond a Boundary: Black Lives and the Settler-Native Divide,” William and Mary Quarterly 76, no. 3 (2019): 417–26.

↑ - 21

Saidiya Hartman, Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Social Upheaval (New York: Norton, 2019), 270–71.

↑ - 22

Kathryn Yusoff, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 9.

↑ - 23

The particular knowledge field that officiated that division of matter was the modern science of geology. Yusoff, Billion Black Anthropocenes, 2, 7, 9.

↑ - 24

My list of subjects and objects that have endured forms of colonial calculation and domination is by no means exhaustive, nor is it intended to flatten critical differences between those forms and their responses. The re-worlding I imagine is, above all, an assemblage operating amid (and against) racial ideologies that have shaped ideas of and outcomes for that which go by “human” and “nonhuman.” Assemblage thinking that has nourished this project includes the following: Arun Saldanha, “Reontologizing Race: The Machinic Geography of Phenotype,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24, no. 1 (2006): 9–24; Ben Anderson, Matthew Kearnes, Colin McFarlane, and Dan Swanton, “On Assemblages and Geography,” Dialogues in Human Geography 2, no. 2 (2012): 171–89; and Alexander G. Weheliye, Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014).

↑ - 25

For Purifoy, rabbits, birds, scorpions, and lizards could be seen in the area from afar but not heard, much like artists who are “extremely sensitive to noise, because they spend quiet times in their head.” “African-American Artists of Los Angeles,” 164.

↑ - 26

On social death as the state of Black life after slavery, see Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982).

↑ - 27

McKittrick, Dear Science and Other Stories, 11.

↑ - 28

My use of the past conditional tense follows Saidiya Hartman’s method of “critical fabulation”: a situated, speculative epistemology of what could have been, of what can be imagined in the face of grand narratives and their archival methods that yokes Black people to the commodity form. Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe 26, no. 2 (2008): 1–14. On intra-action as the dynamism of forces that produce agency itself, see Karen Barad, Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2007).

↑ - 29

J. Kameron Carter and Sarah Jane Cervenak, “The Black Outdoors: Humanities Futures after Property and Possession,” Franklin Humanities Institute, n.d., accessed August 2, 2021, https://humanitiesfutures.org/papers/the-black-outdoors-humanities-futures-after-property-and-possession/.

↑ - 30

“A Note to the Viewer,” in Noah Purifoy: High Desert Assemblage Artist (Göttingen: Steidl Books and the Noah Purifoy Foundation, 2015). This art book consists of the material Purifoy had compiled for his scrapbook-style tour in 1997.

↑ - 31

In Elizabeth Povinelli’s study of power in settler late liberalism, she argues that the onto-epistemic formula of “Life” versus “Nonlife” is unraveling, as it should, given how it has crowded out Indigenous “critical analytics and practices of existence.” I also heed here the cautions made by scholars like Zoe Todd, Diana Leong, and Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, who have demonstrated that when European thought posits that matter can come to matter on its own terms, it does so by effacing and/or extracting Indigenous cosmologies and Black flesh. Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 6–9; Zoe Todd, “An Indigenous Feminist’s Take on the Ontological Turn: ‘Ontology’ Is Just Another Word for Colonialism,” Journal of Historical Sociology 29, no. 1 (2016): 4–22; Diana Leong, “The Mattering of Black Lives: Octavia Butler’s Hyperempathy and the Promise of the New Materialisms,” Catalyst: Feminism, Theory, Technoscience 2, no. 2(2016): 1–35; Zakiyyah Iman Jackson, “Outer Worlds: The Persistence of Race in Movement ‘Beyond the Human,’” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2–3 (2015): 215–18.

↑ - 32

Sharpe’s references for the rearrangement are Hortense Spillers’s account of the dissolution of gendered subjects into fungible objects in the slave ship’s hold, as well as Fred Moten’s sense of blackness as a break that “anarranges every line.” Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” in Black, White, and in Color: Essays on American Literature and Culture, edited by Hortense Spillers (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 203-209; Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1. For Sharpe, this is one valence of Black being in the wake of slavery; a sense of blackness that has “difficulty of sticking the signification,” where “girl doesn’t mean ‘girl,’ but, for example, ‘prostitute’ or ‘felon.’” Christina Sharpe, In the Wake: On Blackness and Being (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 76–77.

↑ - 33

Susan L. Chaney, “Artist Makes Unusual Medium Talk,” Hi-Desert Star, August 19, 1986, 64, clipping in Noah Purifoy Papers, 1935–98, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

↑ - 34

“African-American Artists of Los Angeles,” 51.

↑ - 35

Exemplifying the participatory nature of the museum, this structure was initially intended for rotating exhibitions and once included plaster figures of real people that were cast by students at Claremont College in Pomona, California. In an example of the site’s vulnerabilities, a building inspector once requested that The White House be torn down or brought up to code. Purifoy’s solution was to remove the walls and ceiling and lower the floor two feet. Noah Purifoy: High Desert Assemblage Artist, 17, 113.

↑ - 36

For images of Endless Column, see “Brancusi’s Endless Column Ensemble,” World Monuments Fund, accessed February 12, 2022, https://www.wmf.org/project/brancusi%E2%80%99s-endless-column-ensemble.

↑ - 37

Kristen Scharkey, “What Would Noah Purifoy Do?,” Desert Magazine, May 31, 2017, https://www.desertsun.com/story/desert-magazine/2017/05/31/what-would-noah-purifoy-do/357026001/.

↑ - 38

For a study of those conventions, see Jane Tompkins, West of Everything: The Inner Life of Westerns (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 76.

↑ - 39

Sean Milanovich (Cahuilla) quoted in Rau and Jones, Tending Nature; Scott Wilson, “A Massive Aquifer Lies beneath the Mojave Desert: Could It Help Solve California’s Water Problem?,” Washington Post, March 3, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/national/a-massive-aquifer-lies-beneath-the-mojave-desert-could-it-help-solve-californias-water-problem/2019/03/03/a5d8fe14-354e-11e9-af5b-b51b7ff322e9_story.html; Rebecca Cohen, “Water Bandits: How One Company Almost Got Away with Draining the Mojave,” EarthJustice.org, March 26, 2021, https://earthjustice.org/features/mojave-national-monument-water-legal-fight-cadiz?gclid=CjwKCAjwuvmHBhAxEiwAWAYj-JhjeF1vpDkJiVyT3NgCC437vbM2iS5NwwW7Q0H38lCskipTIr47uRoCulIQAvD_BwE; “Lawsuit Targets Trump Administration’s Last-Minute Pipeline Approval for California Desert Water Grab,” EarthJustice.org, March 23, 2021, https://earthjustice.org/news/press/2021/lawsuit-targets-trump-administrations-last-minute-pipeline-approval-for-california-desert-water-grab.

↑ - 40

Richard Wright, The Man Who Lived Underground (New York: Library of America, 2021), 51, 52, 92, 119.

↑ - 41

Malcolm Wright comments in “Richard Wright’s The Man Who Lived Underground: A Conversation with Julia Wright, Malcolm Wright, and Kiese Laymon,” Library of America Presents, April 15, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f9y0gRa5gDE.

↑ - 42

Wright, Man Who Lived Underground, 113.

↑ - 43

Lipschutz, “A NeoHooDoo Western,” 44.

↑ - 44

Ralph Ellison, “From Invisible Man, Prologue,” in The Norton Anthology of American Literature, vol. 2, 3rd ed. (New York: Norton, 1989), 1913.

↑ - 45

Noah Purifoy: High Desert, 127.

↑ - 46

In 1989, the desert tortoise was listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act (established in 1974), thus prohibiting its removal from, or harassment in, its habitat. In 2020, it was temporarily listed as “endangered.” Luis Sahagun, “Imperiled Desert Tortoises join California’s ‘Endangered’ List… at Least for Now,” Los Angeles Times, October 14, 2020, https://www.latimes.com/environment/story/2020-10-14/desert-tortoises-join-california-endangered-list-for-now.

↑ - 47

Shawn Michelle Smith, “Photography, Darkness, and the Underground Railroad: Dawoud Bey’s Night Coming Tenderly, Black,” American Quarterly 73, no. 1 (2021): 25–52.

↑ - 48

Leigh Raiford, “b.O.s. 11.1/Untitled #17 (Forest)/Leigh Raiford,” ASAP/Journal, July 16, 2020, https://asapjournal.com/b-o-s-11-1-untitled-17-forest-leigh-raiford/. Raiford cites Torkwase Dyson, “Black Compositional Thought: Black Hauntology, Plantationocene, and Paradoxical Form,” in Dawoud Bey: Two American Projects, ed. Corey Kelley and Elizabeth Sherman (New Haven, CT: SF MoMA and Yale University Press, 2020), 78; Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017); and Tina Campt, A Black Gaze: Artists Changing How We See (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2021); Sharpe, In the Wake; and Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

↑ - 49

Fred Moten, “Blackness,” in Keywords for African American Studies, ed. Erica R. Edwards, Roderick A. Ferguson, and Jeffrey O. G. Ogbar (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 27.

↑ - 50

On the exclusions of wandering, Sarah Jane Cervenak notes that the movement can invite presumptions of human agency that do not apply to wanderers who are subject to surveillance or whose movements might be illegible as exterior, bipedal kinesis. Sarah Jane Cervenak, Wandering: Philosophical Performances of Racial and Sexual Freedom (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014), 4.

↑ - 51

Noah Purifoy quoted in Chaney, “Artist Makes Unusual Medium Talk.”

↑