Toxic Debt: A Conversation on Land, Speculation, and the Afterlife of Ultra-Deep Mining in Contemporary South Africa

Sipho Shongwe in the East Rand, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Andile Mukhari.Since the 1970s, South African mining companies have found new ways to capitalize on the movement and reconstitution of mined earth by “reprocessing” the waste products of underground mining. At the same time, these companies have entered increasingly speculative land and real estate markets. Amid growing concerns about how surface reprocessing increases exposure to toxic materials as well as toxic assets, this edited conversation between veteran union organizer Sipho Lucas Shongwe and architectural historian Megan Eardley documents our efforts to grasp the spatial dynamics of “toxic debt.” As we learn from scholarship on architecture in Africa that emphasizes its relationship to land, land-based economies, and forms of life, we depart from literature that concerns the way architects have shaped national land reform and development programs since the mid-twentieth century.1 Where such literature describes how African liberation movements and post-colonial states struggled to transform the colonial infrastructures that sustained industrial extraction, we center miners’ knowledge, as well as community archives, to account for the industrial production of post-mining landscapes.2 In (post)apartheid South Africa, we argue, surface reprocessing operations are particularly important, and challenging to understand, because of the way they work to scramble time and place; even as they dissolve landforms, they compound historic exposure to heavy metals and radioactive material. Foregrounding Shongwe’s knowledge of the country’s surface reprocessing plants, his efforts to organize labor in an era of rapid political and economic change, and the way his own land claims have been impacted by developments in the mining industry, we reflect, finally, on the way architectural historians might engage multiple temporalities and sites of analysis in an effort to understand the expansion of extractive operations, as well as new demands for life and labor in places that may not sustain biological processes of growth or reproduction.

Portrait of Sipho Shongwe in the East Rand, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Andile Mukhari.

I. On the Afterlife of Ultra-Deep Mines

In the second half of the twentieth century, South Africa’s mining houses developed the deepest gold and uranium mines in the world. At the same time, they pushed millions of tons of crushed rock and process effluents aboveground, generating a seam of industrial waste that runs across the country. Critical studies of this waste have long centered on its relationship to Johannesburg, where visual contrasts between the city built on gold and the mine dumps that surround it have driven debates about the way both life and labor are governed for the purpose of capital accumulation.3

In the early 2000s, as South Africa struggled to consolidate a multiracial democracy, political theorists, including Achille Mbembe, grappled with the racist insistence that the death of Black mine workers was necessary for the advance of civilization, while Black life continued to be treated as part of the industry’s waste. Studying colonial representations of the mine dump as a mausoleum, Mbembe explored how the use and exchange value of Black labor came to be obfuscated. Violently suppressed wages, he argued, ensured that methods to measure work were so emptied of meaning that they facilitated “the abolition of the very meaning of quantification.”4 Just before the 2008 financial crisis popularized notions of “toxic debt,” Mbembe speculated on the way still-visible forms of mine waste shaped demand for luxury housing developments, malls, and casinos among heavily indebted and underemployed Africans moving to Johannesburg. Attending to their investments in social and economic mobility, as well as the way the commercial treatments of surfaces and quantities in this landscape were “premised on the capacity of things to hypnotize, overexcite, or paralyze the senses,” he stressed how material analysis could help us come to terms with “the dialectics of indispensability and expendability of both labor and life, people and things” in (what is often called) the new South Africa.5

Today, the physical movement of mined material is driving new research on toxicity. Attending to the accumulation of heavy metals and radioactive material in and beyond Johannesburg, architectural historians are building on STS frameworks to describe the problem of toxic exposure in biogeochemical and legal terms. While Lindsay Bremner argues that deep mining operations have generated a “toxic reality” through “new associations of science and politics as well as air and earth,” Hannah le Roux and Gabrielle Hecht describe how inadequate state regulation of mine dumps and land remediation programs “render ever-larger plots of land unfarmable, and ultimately unlivable.”6 To understand how “new forms of political life” are “assembled” in these contexts, they track the production and sale of radioactive bricks, metals, and other building materials sourced from the industry’s dumps. Following the distribution of self-help construction schemes as well as small scale manufacturers, they analyze global structures and local strategies that weaken regulation and knowledge of the material’s origin and composition.7

The scale and speed at which mined material is moving makes this task particularly challenging. Because techniques used to treat ore in the first half of the twentieth century sent significant amounts of gold and uranium into mine dumps, the most technically adventurous of the country’s mining houses developed “surface reprocessing” designs to recover residual metals through a series of physical and chemical baths. Since the mid-1970s, their technologies have promised to automate extraction, eliminate health and safety concerns associated with deep shaft mining, secure more predictable payloads, and guarantee a continuous process of extraction, while reclaiming large areas of land for industrial and residential development.

Slurry pipeline in the East Rand, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Andile Mukhari.

Just as South Africa’s mining houses have expanded into property management as well as real estate, surface reprocessing has spread occupational hazards to people and land rarely associated with industrial labor.8 Retired miners and labor organizers now call our attention to the number of children being born with epilepsy, a neurological condition that has elsewhere been linked to in utero exposure to radiation. As unemployment and medical costs rise, they challenge us to consider not only the limits of life but the conditions under which the “world-transformative possibilities of collective labor” can be “separated from the power to act.”9 To this end, we have begun a collaborative study concerning the design of one of South Africa’s oldest and largest surface reprocessing complexes.

As an architectural historian, Megan Eardley asks what the design and use of the complex can teach us about the industry’s changing interest in life and labor. As a retired miner, labor organizer, and traditional healer, Sipho Lucas Shongwe has been studying the social and environmental impact of surface reprocessing for more than thirty years. He has carefully saved promotional materials, annual reports, and union communications, developing his own archive of the mining industry’s extraordinary promises, successes, and failures. When the two of us met in 2020, he was part of a national network of academic researchers and policy experts working to establish a framework for reparations in mining-impacted communities in South Africa.

The surface reprocessing plant presents both of us with a series of conceptual and methodological questions. Some of these are questions of access. While the plant is visible behind a series of razor wire fences and its pipeline is accessible alongside the largest highway into Johannesburg, the actual limits of the operation are not easily identified, as it spreads and concentrates radiation, heavy metals, and acid mine water beyond visibly mined landscapes. When the call for papers for the Aggregate Toxics project was published, Eardley asked Shongwe if he would consider discussing the way the plant appears in his archive. Following models established at the intersection of oral history and architectural history, she proposed that the structure of the conversation could emerge out of his reflection on a photo or published plan.10

Privileging Shongwe’s current understanding of documents he collected as he navigated shifts, organized workers, and planned strikes alongside the founding members of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) may help us identify the contours of a larger study. Each of us has edited the transcribed conversation, adding details and corrections that move toward a shared understanding of the material dynamics of toxic debt, as surface reprocessing scrambles time and space to make room for new investments. To make our conversation more legible to architectural historians and to toxics researchers outside of South Africa, we have reordered and edited parts of the conversation. We present here three sections, which reflect our current understanding of surface reprocessing and its impact on land claims, efforts to organize labor in an era of rapid political and economic change, and concerns about occupational and environmental exposure across generations.

II. Reclaiming the Land

Surface reprocessing plants built in the second half of the 1970s were designed to reprocess mine waste. As miners worked to remove sulfur from “the slime,” companies speculated that they might “eliminate a potential source of pollution (acid mine drainage) from the tailings.”11 This highly acidic saline solution is produced when sulfitic minerals are exposed to oxygen and water. Since mining operations introduce oxygen to deep geological environments where these minerals are abundant, they often begin the chemical process that will leach heavy metals out of the strata along with the water that runs through the mine. In 1976, scientists were already reporting that “the metal pollution of inland and coastal waters in densely populated and highly industrialized areas” surrounding gold and uranium mines had “reached dangerous proportions.”12 Where water used to process mine waste was discharged into the Witwatersrand’s largest rivers, sediment and water samples suggested that “acid leaching of iron, manganese, nickel, cobalt, copper and zinc had effected a 1,000–10,000-fold increase of metal concentrations compared with that of unpolluted river water.”13

Acid mine drainage doesn’t just disrupt aquatic ecosystems and functions; it alters the quality of the earth. As the water seeps into the ground, it kills the vegetation that nourishes the soil and reduces that soil to dust. Industry speculation on this “potential source of pollution” effectively produced toxic assets avant la lettre.14 Surface reprocessing operations have not stopped the spread of acid mine drainage, environmental exposure to radiation, or the accumulation of heavy metals.

Pipes in the East Rand, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Andile Mukhari.

Reclaimed land, meanwhile, has not been able to hold its value. In the outer areas of Johannesburg, on and near former mine-waste sites, developers with plans for a shopping center, hotel, and private residences have found water nearing a pH of 2.0 and a concentration of uranium high enough to be classified as a “radiation hotspot.”15 A luxury retirement village was effectively abandoned after residential exposure to radioactive airborne dust was documented and attempts to auction the building for industrial use failed.16

Megan Eardley (ME): Before we started working on this interview, I didn’t know that you were fighting to reclaim your family’s land.

Sipho Lucas Shongwe (SLS): Yeah! Yeah. You know, amongst the land that was—the people have just claimed and it hasn’t been given back—the land of my forefathers is one of them. It’s lying in a farm in a town 350 kilometers from here, in Mpumalanga. That is along the Swaziland border. There is a town there called Amsterdam. When these whites came into the land, that was the land of my great-grandfather. Especially that Amsterdam, because his grave, it’s amongst the mountains there, just about a kilometer from town. My great-grandfather was a renowned traditional healer. He was an advisor to the Zulu king, though I wouldn’t know which king it was. In the royal family, a king would only have one traditional healer to look over his whole family—irrespective of how big it is—so that’s what happened with my great-grandfather. He was a traditional healer to that king and advisor to him as well. Time and again I have to visit him, especially me, because I’m the heir, and as the heir I also possess his traditional healing.

ME: What was the name of the land before white settlers called it Amsterdam?

SLS: You know, you wouldn’t use one name, because it was different villages in one. But it’s quite huge, very huge. And there’s also a dam which was built from 1965 to 1970. My father died there in 1966 whilst working on that dam during its construction. That dam is so important to the mining industry here because it supplies one of the biggest fuel companies, SASOL [Suid-Afrikaanse Steenkool-, Olie- en Gasmaatskappy]. They pump water 200 kilometers from that dam to SASOL. The water they use at SASOL for process water [non-drinkable water used in industrial processes and facilities] comes from that dam.

ME: I just saw some research on the history of SASOL, which emphasized how its oil-from-coal program powered the development of ultra-deep mining in the agriculturalist Free State. The historian who undertook this research, Stephen Sparks, has argued that its company town, Sasolburg, was considered a model for apartheid planning, while state-sponsored industrial

development demonstrated apartheid’s modernity to national and international audiences.17 In many ways, your family’s history—your inheritance even—is at the center of this history.

SLS: That’s correct, that’s correct. And you know, after the construction of that dam, they started moving, even my own people, my own family who would stay there. My grandfather was born and brought up in that area. So time and again, from the urban area, we’d visit there, especially me, because my grandfather loved me so much, like I say. It was because he knew I am the heir. So that I wouldn’t lose touch, I would even be able to take public transport and visit them. As I tell you, it’s not very, very far. It’s roughly 50 kilometers, so not very far.

ME: Do you still have family there?

SLS: That’s correct, that’s correct. Even some of the family members now. Some of them would be taken there after their death. The last one was my mother, because my father was buried there. We’ve got a cemetery of all the members of the family. So even if someone dies here, in the urban areas here, around Joburg, he will be taken down to be buried there. So almost all the members of my family are there, with the exception of my great-grandfather: my grandfather, my grandmother, my father, and some of his brothers—two brothers; the last member was my mother, in 2016. The farm is under that Afrikaner, but he does give us permission to visit, because if he doesn’t want to give us permission, we’d have to go and apply at the nearest magistrate court, which is Amsterdam. A lot of farmers have been told by the government that now that we are waiting for the proclamation of land expropriation without compensation, those families must be given permission.

ME: So the government’s temporary solution is that white farmers can keep living on land that was stolen, but they have to let you come and visit?

SLS: That’s correct. So, time and again, if we are to visit there, the cemetery there, we ask for permission from the owner. Because in that very area where the cemetery is, he has got a big game farm there. So there would be the game rangers looking for poachers.

ME: That’s—wow—it sounds like it’s still such a threatening, hostile relationship.

SLS: It’s very, very difficult presently, now that life is confined in the urban areas. Because if we were still within that land … there is a lot that I’ve grown to understand, when I go on this traditional healing venture on my own. Now it becomes difficult to gather a lot. I’m still on a learning curve as we speak now. Because you know in traditional healing there’s a lot to learn, because they come with new things every day. Like I said, they communicate with you through dreams. Yeah, so, there would be times if you go and consult, they tell you that your ancestors actually are not happy with you having settled in the urban areas. Because at least you’d be doing a lot of things in the rural area. Then it becomes difficult, like for myself, when you are waiting for a big land, and you have to accept being confined in some of the small areas where a lot of your people were settled during the Apartheid.

Across the whole area, we’ve got to make a lot of noise before the government can stand up—to hold the mine bosses responsible. Because that is also their problem, the rehabilitation of whatever land they destroyed, during the period of their operation.

There is a law now that money must be set aside for the rehabilitation. Following surface reprocessing, mined sites were supposed to be rehabilitated, at least by planting grass—loam soil and grass that can sustain the wind—so it would not blow as it blows during the winter season, during July. They’ve got to plant trees around there, because those trees then become a windbreak. But at the end of the day you don’t know where that money went to. We’ve got to make noise, then the government will have to stand up, and be very strict, and investigate where the money went.

Sipho Shongwe in the East Rand, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Andile Mukhari.

III. Organized Labor

For nearly a century, South Africa’s mining industry depended on a migrant labor system that exploited colonial borders to recruit, annually, hundreds of thousands of Black men with limited access to formal education to work poorly paid temporary contracts. Surface reprocessing plants rejected the labor model on which deep mining was built. On the surface, companies need only a few hundred employees with training in mathematics and chemistry to keep the material in the pipelines moving.

In Shongwe’s archive, we read company brochures that promised new benefits for all workers employed in surface reprocessing. While racial segregation was legally enforced when it opened, their plant offered a “uniform wage structure,” an “equitable scale of fringe benefits,” and “model conditions of employment for both White and Black employees.” In its first year of operation, one brochure notes, the plant won business achievement awards in recognition of the company’s “outstanding contribution to the development of the South African economy” and “the vital role” it played “in demonstrating to investors both in South Africa and overseas the resilience of the business community of South Africa and its faith and confidence in the future of the country’s economy.” The company claimed that “the imagination of the public” was “captivated by the romance associated with bringing new life to the East Rand.”18

The promise of new life (for investors, if not the harder-to-define “public”) remains powerful. In the mid-1970s, one company acquired 19 slimes dams (dams used to hold mining waste) calculating that they could reprocess 378 million tons of material from these dams at a rate of 18 million tons per year. By modifying the original plant’s design and expanding operations to include more dams, the company extended its projected life by nearly a decade; the plant scheduled to close in 1997 was able to remain open and active until 2005. At this point, 350 kilometers of pipelines, 22 slurry and water pump stations, and two metallurgical plants would have to be safely shut down or dismantled. Thanks to laws passed during the transition to democracy in South Africa, the company also had an obligation to retrain employees. But when the plant was sold and reopened, in 2008, the company effectively passed on its obligation to both the site and its employees.

Thanks to the industry’s historical use of job reservations and segregated housing, Black miners and their families have been exposed to heavy metals and radiation that may cause autoimmune conditions as well as damage to tissues, organs, and the genetic material that are passed down for generations.19 As high unemployment rates continue to compound concerns about the kind of life surface reprocessing can cultivate, we discuss strategies and challenges of organizing labor at the surface reprocessing plant, as well as their relationship to the struggle against apartheid.

ME: I just found a report from 1987 describing how the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), then the largest union representing Black mine workers in South Africa, occupied your plant during an industry-wide strike. This report said there was sabotage at the plant. What did that look like?

SLS: This happened at the height of NUM’s power, when membership was above 500,000 members. At the time I was the regional secretary for the Witwatersrand area, so I was engaged with more than 150 mines. The plant was quite unique in the way it used semi-literate to literate workers and was independent of the Chamber of Mines, the mining federation. The strike was about a dispute over a salary increase. The plant’s management was clever: they locked everybody inside the complex for one week during the strike. That meant the number of people participating in the strike was less, as the rest were locked outside.

The plant’s parent company had their own media department, which covered everything that happened during the strike. Their media crew was with us throughout. We are talking about TV cameras and everything. A detailed video was made and delivered to the human resources superintendent’s hands. It was supposed to be played in the Labour Court as evidence of unruly behavior on the part of union members. I utilized every trick in the book to retrieve this valuable evidence. This happened the day before the court date. I drove the whole night to hand it over to Mr. Cyril Ramaphosa, who at the time was our general secretary. These activities happened under very stringent conditions, as you would remember it was during the era of the Apartheid regime. Such activities would be regarded as acts of terrorism.

ME: Wow. You know, I’m especially struck that the management’s response to the strike was to lock the complex. Many people who have analyzed the architecture of mining compounds argue that the design of on-site housing for an all-male Black migrant workforce was something that transformed mines into “institutions of incarceration” as well as “instruments of coerced labor” across southern Africa.20 Since the 1990s, studies have described how midcentury compounds invoked “a powerful spatial imagery of isolation, confinement, and encapsulation,” even as research on the micropolitics at multiple mines demonstrates that there are important social and political connections between the industrial mine and its hinterland, which both shape and limit management strategies to control migrant workers.21 The design of surface reprocessing plants seems to separate questions of housing and industrial production, so I am interested in how the fight to improve living and working conditions was brought to the plant. I hope we can keep talking about how your work during the strike changed your knowledge of the spaces you’re operating in. As you describe the use of TV cameras, it seems critical to understand the company’s efforts to control the appearance of miners, as well as the material impact the strike had on the plant’s production. Can you say more about how you were able to take these risks as a union organizer? What models and support did you have? Your parents went to work for the mining industry, right?

SLS: Not necessarily for the mining industry. It was during the time of industries that sprang up after the gold rush. They would work as factory workers.

ME: I see. So was it your grandfather who first moved from the rural areas? Or your father?

SLS: No, my father. My grandfather has never moved from the rural farm, which is Amsterdam. He has been staying there all the time. We would only move, go and visit them, during long weekends and on holidays.

ME: I see, so your parents moved for work, and then you were born… .

SLS: In the urban areas, that’s correct, in Germiston, to be precise. Ten kilometers from Joburg. The second-biggest town to Joburg. Even during the early gold rush you’d have a lot of mines around the Joburg area and number two to it would be Germiston. My uncle was in the transport industry. So those were the people who would move around. He was also very politically minded, so he knew of these politicians who were moving their kids out of the country to go and get better education, and he followed suit.

ME: How do you think he got involved in the politics?

SLS: Like I say, he was moving around a lot because he was a driver of trucks. I remember at one stage he was transporting goods to neighboring Botswana. He was one of the good drivers that would be sent to Botswana, Zambia, to the DRC. So he knew these places. And he was better educated in the family, so hence he was so politically minded. He knew, at the height of those Black mass protests, a lot of the politicians who were the targets because they were schoolmates. When he fled the country, they were looking for him. That is my uncle. So that is how we got to flee the country with him to neighboring Eswatini. And it helped us, because we wouldn’t have gotten that good education at the time. That’s where quite a lot of these politicians’ kids were schooling. The Mandela kids schooled there as well.

ME: So how many kids from your family went with your uncle?

SLS: Only myself. I schooled there with his kids as well, so we are still very close, even today. One of them is an instrument engineer working for PetroSA in Western Cape. We communicate almost every day. We are so close, even to this day. When was it—was it last month?—when you phoned me and I said I’m in Ermelow, in Mpumalanga? Yeah, I was at his house. He was at home on the weekend.

ME: So how old were you when you left South Africa?

SLS: Ah, still very young. Because we actually started primary education there. My uncle went there in 1960. Because around there, in Eswatini, there was a big pulp company that had just opened. The owners were from Great Britain. And they recruited a lot of people. And at the time there was no border between Swaziland and South Africa, so it was easy to go there as well. A lot of people then were educated, and they would get better positions. At the time, when he died, he had already been appointed transport manager.

ME: Wow, it sounds like your uncle really understood that industry well and was leading a lot. I can see how that would help with political organizing, to understand transportation networks and be able to move things around.

SLS: Yeah, yeah! All the logistics.

ME: Was it scary to go with him?

SLS: No, at the time, it wasn’t as scary as it became later. Because later on, I remember when I was still schooling there, in my last high school days, the South African security forces grew in leaps and bounds, and they would be even able to attack the neighboring countries.

There was one military camp we organized next to where I was schooling in high school which was later attacked by the security forces. If you knew South African politics—there was this girl who—her remains were never found to this day. The news went around in all newspapers, TVs. Her name was Nokuthula Simelane. She went to the same school as I.

I was senior to her; when I was doing my senior matric[ulation], she was doing form two. Then later on, she was appointed as a courier. She would take letters, correspondences, to the offices here around Guateng, around Joburg. When they kidnapped her, they kidnapped her at Carleton Center. What would they do if they catch one of your members? He or she would undergo interrogation until she or he tells him everything of your activities. So when she got caught, they knew exactly what she was doing in her job as a courier for the ANC in exile. ..

Eh oh, those were very difficult times here in South Africa. During the height of the political upheaval—it’s just that the family does not have proof—but it is known that she was killed and burned to ashes. Eh.

ME: Dear Sipho, I hope that we honor her memory.

You’ve mentioned before that you were lucky to survive an attempt to firebomb your home. Do you want to talk about that?

SLS: As I said, it was during the time of political upheavals. My name and a few others were put in the spotlight, and I was targeted on the 24th, 25th of June 1985; that security branch struck my house. One bomb could not explode, the other one died in the hand of the assailant. Because of that, at a later stage, I had to go and appear at Pretoria High Court, for a period of six months, because they said that I was a member of the MK [Umkhonto weSizwe (Spear of the Nation), the armed wing of the African National Congress] and they wanted to charge me for furthering the aims of a banned organization. After that six months was the first democratic election. Then even the whites who were caught red-handed must appear before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to explain their participation in the political activity. I appeared with others, but we were never charged because, as I said, it was nonsense even from them. However, most of my library got lost when I moved away from the home that was bombed, coming here where I stay.

Aerial footage of an East Rand tailings dam, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Tim Wege.

IV. The Plant

When we examine company photos of the surface reprocessing complex, particularly photos that document its construction and early days of operation, we are struck by the pains that were taken to show the pipeline, tanks, and tailings, with no visible presence of miners. This absence is especially palpable in booklets printed in anticipation of the plant’s closure in 2005. Where workers are visible, they serve to underscore the monumental scale of the plant, but there is no attempt to document the process by which they liquidate and manage the movement of mine waste. Corporate management, engineers, and plant operators are all depicted in professional head shots, as though they all work together in an office. The company’s equalizing photos deny important differences in their employees’ skills, work experience, and exposure to toxic materials.

ME: You’ve told me before that during the first years of operation the plant was segregated—that only white workers could work in the gold plant. I think you said managers claimed Black workers would steal the gold. It seems like this was already a little embarrassing to the company, because the way that was expressed was, rather than saying “white workers,” people would say “scheduled workers.” That was a kind of code for “white workers.”

SLS: That’s correct. Actually it was not even the company laws—it was the country’s laws that only whites could work in the gold section.

After some years, they discovered that there’s still a lot of gold in the tailings leaving the plant, so they built a Carbon-in-Leach (CIL) circuit [to extract trace amounts of gold]. The slurry from the flotation plant gets pumped to CIL tanks, eleven of them in a series; it just gradually flows from one tank to the other. Then they will feed the tanks with fresh carbon, which is imported from somewhere in the United States. Once it goes from one tank to the other, it is fully loaded with the gold particles, so it is then called “pregnant carbon.” This pregnant carbon which has been picked from these tanks is then sent to the elution column. That is where it gets washed with a variety of chemicals, like your cyanide, so as to wash the gold particles picked up in the tanks.

ME: Could you say more about the work you did?

SLS: I commenced as a process operator and quickly advanced to become a foreman because I had my matric, with science subjects. Actually if you had your matric, with chemistry and mathematics, it would help you a lot, as the operation entails a lot of metallurgical knowledge and quick calculations.

We had to understand how much material, measured in tons, is being moved from the reclamation sites—pumped through the pipeline and into first the flotation plant, then the uranium treatment plant, the gold recovery plant, the acid plants, and finally that CIL. We had to calculate how many tons were being pumped from one plant into the next. As a process operator, you do take readings hourly. If you have a full understanding of how all this operates, you stand a good chance of getting promoted first to senior operator, who does this calculation on a daily basis, then to operations foreman.

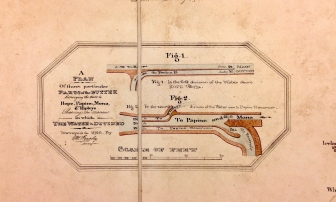

ME: Looking at the images you shared with me, from the company’s records, I’m curious about the way the process you are describing is documented as though it could be automated.

SLS: Which never worked! I remember we struggled for two to four years trying to force the automation, which was initially what it was designed for, which never worked! And slowly, or gradually, we had to revert it to manual. There were some few sections here and there which remained automated, but the bulk of the operation had to be converted to manual operation.

ME: What made it so hard to automate? I’m trying to understand how a mining company could enter the logic of the postindustrial economy, where capital is invested in speculative temporal processes rather than industrial production. This model doesn’t seem to need many workers, so what happens to organized labor, collective bargaining? How is toxic exposure distributed?

SLS: You know, one scientist even said they have now been proven wrong, that this operation cannot be fully said to be science. It is an art.

ME: Can you describe this art more? What were you doing when you first started out as a process operator? Did you have a work station in the plant?

SLS: No, no—Ha! No. There’s not even a single one who stays in the office. You are in the field! You are the one who knows if they are pumping so much the plant cannot take it. So you have to pass that message to the person who runs the shift—who would be the foreman—who will contact his counterpart on the other side. That is the reclamation site where the slurry is coming from; the plant cannot take the amount of slurry being pumped in. The other way around they are encountering problems as well. It couldn’t be too much or too little; it becomes a problem to the process.

At times, with a clever operator working, he’ll play around with the valves so that even when the other section, that is, your reclamation section, is pumping too much material, you can still play around with the valves for some time just to control the flow. Because you cannot say to them, “Start, stop, start, stop,” that is, “increase, decrease, increase, decrease.”

ME: So, the men that are working at the mine dump, they have these big pressure washers, they’re washing down the slag, and they’re making it into this slurry so that they can liquidate mine waste, send it through the pipeline, and extract the uranium, gold, and acid that was left in the dump at the plant.

SLS: Yeah, they’re breaking it down into a form of slurry, because you know it was just in a hard surface… . So using these high-pressure water jets, they break that into, say, the form of mud, which then gradually flows into very big screens, to take out unwanted materials, like logs. There are even trees that grow there on the surface of the dam. All the unwanted material, called the overhead, is being screened. That remains on top, and then you can discard it. Then the wanted material is being sifted through these screens to a kind of holding tank. Then it is ready for the pipeline. The biggest of all the pumps is called a d-frame pump. Sometimes you get six pumps connected in a series that can pump that slurry a distance of 30 to 50 kilometers. It delivers that pumped material into the reception pachucas in the central plant. A reception pachuca is a cylindrical tank with a conical bottom. It contains a pipe that is lined up with the leaching tank, so when compressed air is introduced at the bottom of the pipe, it functions as an air lift. It keeps that material moving before it reaches the flotation plant.

ME: So that’s where the process operators take over? They’re monitoring how fast the material is getting to the first plant?

SLS: Yeah, that’s correct. These different pumps, you can play around with their speed—you can increase their speed or lower their speed. That is to allow the person on the other side, at the reception pachuca, to decrease the speed if he is getting too much material.

It must be someone who truly understands the problems that can be encountered if you increase or decrease, because it can break the pumps.

ME: So, as you gain experience as a process operator, can you come to anticipate times of day or certain periods when you know they need to slow the flow? Or even something like the weather conditions?

SLS: Yeah, even the weather conditions! The weather conditions are a contributing factor, because when there is heavy rain, like torrential rainfall, it becomes very difficult for those guys at the reclamation section to operate optimally, because a lot of rain flows down with this material. So they’ve got to cut the rate at which they are reclaiming. Because already there’s material flowing in their loaders.

ME: Right—the rain is kind of doing the work of washing… .

SLS: Precisely.

ME: That makes sense. And are there other factors, like if you knew that the materials were coming in from different mines, could the material affect the flow as well? Or is that too … did you even know where it was coming from?

SLS: Yeah, there are a number of factors. Over time, these big pipes that connect the reclamation area to the plant, they get buildup inside. You see this material when there are shutdowns; not all of it gets drained. You cannot drain all of it. Then that material settles inside. By the time you start up, some of it has hardened inside the pipe. Then it reduces the capacity of that pipe. And at some stage, it breaks again.

ME: I see. Like you said before, with the weather conditions, you know how long there’s been a shutdown, so you know how long things have been sitting in the pipes. You know whether it’s hot so things are going to harden faster—that makes sense. This is the stuff that gets hardened and then it’s moving as kind of a lump. Does it have a name?

SLS: It’s being called scale buildup. You see, Megan, your ordinary kettle, that you use to make tea with, have you ever observed inside? Over time, because you are only using it to make tea… .

ME: Yeah, it gets that calcium deposit.

SLS: That’s correct, that’s correct. That material is calcium hydroxide, because you use that to balance the pH of water. Because when they purify water, at the end they would use chlorine—chlorine gas, which is an acid, so to neutralize if you have got too much of that acid, you’ve got to put lime to neutralize it. So that calcium hydroxide that you see in the kettle, that’s exactly what happens there. And this is analogous to what builds up inside the pipe.

At the level of foreman, or senior operator, you’ve got to have the full know-how of the chemicals that you use in the process. And we call them reagents. These are chemicals that would extract the desired mineral from the material.

ME: All of these chemicals are pumped in?

SLS: That’s correct. Over time, with experience, this is all at your fingertips. So over time, with good experience, just by merely looking at the bubbles visible on the surface of the tank, you can see that there is a shortage of one of these reagents, and you go for corrective action, and then you find that either the metering pump has got some blockages or it has tripped out.

ME: So is there a route that you would take? Would you be monitoring these different sites in a specific order or was a different person posted at each place?

SLS: Yeah. Let me relate this in the capacity of me being a foreman. I would have an operator on the flotation cells. His job is just to monitor the operation of the cells on a continuous basis. So should it happen that whatever problem that has cropped up is above his grade, he can then consult the foreman, who will know exactly if it’s a chemical issue. He’ll have to call the standby fitter to attend to it. At that time, you also have to take corrective action, such as shutting the plant down. If it’s a big problem of that nature, you shut the plant down for the duration.

ME: So, with all the chemicals being pumped into the slurry, is that mixture understood to be toxic?

SLS: No, you don’t talk about that! Because what would happen—that’s another interesting part. And it would often happen that there is a leakage in the pipeline. Or the slurry overflows and runs down the collection lenders off the main plant. Then it would collect at the bottom and join the nearby Sallies spruit.

ME: Where is that?

SLS: There’s a mine nearby called Sallies. Sallies is an acronym for South African Land Exploration Mining Company. The plant was built near this mine, which was one of the richest in the East Rand. Sallies didn’t close down because of the depletion of the mineral; the tunnels underground were flooded. The plant needed water for operation, bulk water for its operation. They were also thinking that once water was pumped out of tunnels that got flooded, they could recommence operations underground.

In the early ’70s, that Sallies mine had to close down because of the flooding. On the plant’s official opening they even made mention of that. That was to the downfall of the company—that water that kills life. Actually, when they opened it, it was a pilot project. They want to go to all these other areas where there was mining water.

The first was built in an area called Florida. They still wanted to open that mine late in the ’90s… . It must have been ‘92, ‘93 the government passed a law saying they don’t want any acid mine drainage to be pumped out of the tunnels. That is when the surface reprocessing plant had to discontinue using that water out of that mine. They had to stop pumping that underground water out.

Many times the cows that drank from that Sallies spruit died. Those nearby farmers took the company to court, and they won the case. So that, to start afresh, they got engineers to come and look into the situation. They had to create ponds to collect all the spillage from the central plant complex. Then we had to get chemicals to treat it first before it could be released. It would then be allowed to join that Sallies springs. So, that is how settling ponds were created. Usually, when the plant started, there were no ponds there, so any toxic material would remain in the pond. But every time the water flows out, it would have to be checked first so that it does not pollute the nearby rivulet or springs.

ME: What was the water source after they stopped pumping?

SLS: They had to rely on the water in areas they already reclaimed. In my plant they had to build an effluent plant, so a lot of water they’ve already used can be circulated, to make up water which they buy from Rand Water Board.

ME: Wasn’t the company making more acid mine water?

SLS: They were! Part of it was purified by the effluent plant, but part of it would still run down into that Sallies spruit … waste running out with chemicals in it. It would run down the drainage system and then join Sallies spruit.

ME: And the pipes they used become radioactive… .

SLS: Ten, fifteen, twenty years down the line it manifests. It becomes very radioactive. Those pipes had to be discarded, because they didn’t want the inspectors from government to find them around the yard. By that time, they couldn’t be sold to any scrap yard because of their toxicity. [For the paperwork] you would fill in the site where that scrap was collected, the transport company, the weigh-bridge, the consigners’ address, and then the proper shipping name, number, class number, radionuclides. Even this form which has data about radioactivity levels, I got it by posting some of my moles inside the operation. I had a guy there when I was there who was one of my junior personnel who worked his way up to foreman, who arranged with the foreman in charge of scrap metal.

ME: So it sounds like contaminated water had to be contained, because it killed cattle, but radioactive pipes—which might appear to be spare parts or part of a maintenance job—could simply be moved around. What year was the lawsuit that forced the company to design the ponds, after the death of the cattle?

SLS: I can’t remember the exact year, but in the mid-’80s. Because I am talking about the section that was under my control.

ME: And these were white farmers?

SLS: Yeah, of course, yes. Those were white farmers.

ME: So the toxicity was measured by the death of the animals?

SLS: That’s correct.

ME: Later, did they establish better thresholds than when-the-cows-die-drinking-the-water-it-is-too toxic?

SLS: Like I’m saying, the development of those settling ponds was during that time. Because any water that would be let out to join the spruit would have to be checked, thoroughly checked that it is okay for consumption by cattle—and even for fish (because there are some dams around that spruit)—before it goes, because that spruit, it runs down until it joins the Veld Dam, which is the main reservoir of drinking water around Gauteng Province.

ME: That was really playing with fire! To have that much water contaminated! So, when these new regulations were put into place and they created these ponds, what were they monitoring? The pH balance? Chemical concentrations?

SLS: I’m talking of a section that was under my control. They only checked the pH balance—that’s all. But in actual fact they were supposed to be checking more than that. Because they would even take that water to bigger analytical laboratories in Johannesburg. So, whatever they discovered there as toxic, they’d just sweep it under the carpet. I knew they were taking samples! I knew they were taking samples, because whenever those people from the laboratory would come to take samples, you would have to be present as foreman to authorize that or to show them around where to take them.

ME: These were researchers from the company, not state regulators, right?

SLS: Of course, yes.

I remember in the early 1980s, there was a team of scientists from Wits that was sent here to the entire plant to sample the content of radiation. When they left, no one amongst the employees was ever told of the findings of these scientists on the side of the radiation content. And for employees working in that very dangerous plant, called the Acid Plant, there were a lot of fumes there, and the radiation content concentration was so high that all the employees in all the shifts (because the plant must run continuously, you’d have your morning, afternoon, and night shift) you’d not walk into that plant not wearing a badge. This badge was supposed to be measuring the radiation content. You’d wear it in every shift, but the employees thereof, for who it was compulsory to wear these badges, were never told of the findings! I would be working in the plant here but also still doing trade union work as well, so I would raise this several times in the meetings.

ME: I’m so struck by this! We’ve been talking about the way the mining industry has tried to minimize its dependence on your labor, especially in the surface reprocessing plants that were designed to completely automate extraction. We know these designs haven’t worked. Companies haven’t been able to establish a physical or chemical process to treat waste that is continuous and contained within the plant. They have depended on your knowledge of weather patterns, land, reagents, and the earth that is being moved through the pipelines. As you’ve just explained, they have also depended on your labor to track the spread and concentration of toxic material. And yet, because they have not shared their findings, it becomes very difficult to understand, and respond, to health concerns associated with toxic exposure.

I’m thinking again about Achille Mbembe’s claim that for generations Johannesburg’s residents have imagined the mine dumps that surround the city to be mausoleums—monuments to the deaths of countless African mine workers.22 As surface reprocessing operations liquidate and reconstitute these dumps, they don’t just capitalize again on land mined by poorly paid African migrant workers half a century ago. They challenge us to consider new demands for life, especially in a context increasingly defined by high unemployment and toxic exposure.

Aerial footage of an East Rand tailings dam, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Tim Wege.

What was the term you used when you were describing the surface reprocessing operation—this term “pregnant carbon”? As a technical term, it refers to carbon that has fully adsorbed all the gold it can hold, but I’m struggling to hold the idea of pregnancy and adsorption together. It seems to conflate gestation and accumulation.

In recent years, critical theorists, including Melinda Cooper, Thomas Lemke, and Sophia Roosth, have described the late twentieth century as a time of new investment in the life sciences. It is not by accident, these scholars argue, that we see significant capital investment in speculative forms of bioremediation, and terraformation, at a time when colonial markets are said to be exhausted and depleted.23 At the same time, the geographer Mazen Labban insists that technical developments in the metal mining industry have transformed mining into a “biologically based industry.”24 Focusing on the increased use of waste material in the feedstock of metallurgical operations, as well as the employment of microorganisms in the extractive process, Labban argues that contemporary industry investments destabilize the analytical distinction between extraction and manufacturing, biologically based and non-biologically based production, waste and resource. These developments fuel the “deterritorialization of metal extraction,” not because they eliminate territorial regimes but because they extend and reconstitute the material basis of the production of value.25

In South Africa, long the world’s largest gold producer, gold mining companies now drive research on land remediation. Since the 1970s, they have consolidated new land and real estate markets in heavily mined, radioactive areas, using technologies that promote a logic of gestation, rather than digestion, and promise the possibility of an endlessly renewable frontier. Sipho, your ancestral knowledge of the land, expertise as a mine worker, and work as a union organizer alert us to the social and environmental costs of this promise and raise difficult questions about the nature of dispossession and inheritance. This conversation underscores, at least for me, the need to expand our study of housing, as well as plant and pipeline design, to account for the ongoing movement of people and land, as well as the evolving relationships between extraction and cultivation.

East Rand tailings dam, August 2024.

Photo Credit: Tim Wege.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Megan Eardley and Sipho Lucas Shongwe, “Toxic Debt: A Conversation on Land, Speculation, and the Afterlife of Ultra-Deep Mining in Contemporary South Africa,” Aggregate 13 (January 2025).

- 1

In doing so, we engage land imaginaries research developed by the Taubman Africa Alliance, as it emphasizes the need to “rethink architecture in Africa based on land, its economies, and ecologies.” By departing from the language of ecology, we hope to expand the discussion concerning non-biological forms of life. As we acknowledge the role of land in spiritual practices, our ambition is to consider its relation to multiple spatial formations, rather than to detail sacred knowledge. For more on the Taubman Africa Alliance, see Africa Alliance, Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, accessed 15 November 2024, https://africa-alliance.org/. For an overview of particular land imaginaries research methods, see Łukasz Stanek and Kwasi Ohene-Ayeh, “Land Imaginaries,” The Gift e-flux architecture, 1 March 2024, https://e-flux-architecture-land-imaginaries.pdf. On the politics of land and life after death in South Africa, see XuMbuso weNkosi, These Potatoes Look Like Humans: The Contested Future of Land, Home, and Death in South Africa (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2023).

↑ - 2

A growing body of critical scholarship on (post-)colonial infrastructure emphasizes how land claims are made through architectural “networks” as well as “vectors of power.” On recent approaches to architectural networks, see Ateya Khorakiwala, “A Black Carpet of Bitumen,” Grey Room 90 (January 2023): 68–93; Ayala Levin, Architecture and Development: Israeli Construction in Sub-Saharan Africa and the Settler Colonial Imagination, 1958–1973 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2022); and Aggregate, Architecture in Development: Systems and the Emergence of the Global South (Abingdon: Routledge, 2022). On vectors of power, see Ginger Nolan, “Cash-Crop Design: Architectures of Land, Knowledge, and Alienation in Twentieth-Century Kenya,” Architectural Theory Review 21, no. 3 (2016): 280–301.

↑ - 3

Since the nineteenth century, landless and dispossessed African men have been recruited to do dangerous, poorly paid mine work on temporary contracts. These contracts, combined with powerful colonial border regimes, have restricted mine workers’ access to the city, while high death rate industrial accidents were commonplace and disease spread between company compounds and impoverished “homelands” (reservations organized by colonial concepts of tribe and ethnicity). On the racial order consolidated in the migrant labor system, see Jonathan Crush, Alan Jeeves, and David Yudelman, South Africa’s Labor Empire: A History of Black Migrancy to the Gold Mines (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1991); Jonathan Crush, “Scripting the Compound: Power and Space in the South African Mining Industry,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 12, no. 3 (1994): 301–24; Donald L. Donham and Santu Mofokeng, Violence in a Time of Liberation: Murder and Ethnicity at a South African Gold Mine, 1994 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); and Zandi Sherman, “Infrastructures and the Ontological Question of Race,” Coloniality of Infrastructure e-flux architecture, September 2021.

↑ - 4

Achille Mbembe, “Aesthetics of Superfluity,” Public Culture 16, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 375.

↑ - 5

Mbembe, “Aesthetics of Superfluity,” 374.

↑ - 6

Lindsay Bremner, “The Political Life of Rising Acid Mine Water,” Urban Forum 24 (2013): 463; Hannah le Roux and Gabrielle Hecht, “Bad Earth,” in Accumulation: The Art, Architecture, and Media of Climate Change, ed. Nick Axel, Daniel A. Barber, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Anton Vidokle (N.p.: e-flux architecture, 2022).

↑ - 7

Bremner, “Political Life of Rising Acid Mine Water,” 465, introduces the language of assembly. Analysis of the “assemblage” of debt and waste is further developed in le Roux and Hecht’s study of radioactive building material. For an introduction to the challenges associated with the governance of nuclear material, see Kate Brown, Plutopia: Nuclear Families in Atomic Cities and the Great Soviet and American Plutonium Disasters (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013); Adriana Petryna, Life Exposed: Biological Citizens after Chernobyl (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2013); Gabrielle Hecht, Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014); and Traci Brynne Voyles, Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015).

↑ - 8

For a discussion of mining companies as landholders, see Gabrielle Hecht, Residual Governance: How South Africa Foretells Planetary Futures (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2023).

↑ - 9

We borrow this formulation from Melinda Cooper and her essential study of reproduction in the late twentieth century. Like Mbembe, Cooper argues that the Marxist concept of delirium can help us better understand the extraction of value in an era of financialization. As she observes, “The question is no longer whether the sign (money) adequately represents the use-value of labor (as fundamental value), rather under what conditions are the world-transformative possibilities of collective labor separated from the power to act.” Melinda Cooper, Life as Surplus: Biotechnology and Capitalism in the Neoliberal Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2008), 179.

↑ - 10

In terms of method, we benefited especially from Sarah Lynn Lopez’s analysis of the US urban–rural Mexico remittance corridor. Her approach brings together micro (people’s stories) and macro (systemic change) scales by integrating interviews and material culture analysis to better reveal how a building boom fueled by remittances entrenches the demand for migrant labor. In her treatment of capital, life, and labor, Lopez focuses on the gap between one’s social life and the ideologies that shape economies and institutions. “The task is to understand this gap: When does the built environment represent or spatially constitute disjuncture and disconnection for individuals and communities?” Sarah Lynn Lopez, The Remittance Landscape: Spaces of Migration in Rural Mexico and Urban USA (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014), 17. Architectural histories that trace the shifting use and formal characteristics of a design intervention are necessary for this method, as are interviews, which bring out workers’ stories about how they experience the built environment and reflect the way different actors position themselves vis-à-vis the past and present landscape. For more on oral history as a method, see Lynn Abrams, Oral History Theory (London: Routledge, 2016); Katrina Srigley, Stacey Zembrzycki, and Franca Iacovetta, Beyond Women’s Words: Feminisms and the Practices of Oral History in the Twenty-First Century (London: Routledge, 2018). On the use of writing in oral history, see Alexandra Kasatkina, Zinaida Vasilyeva, and Roman Khandozhko, “Thrown into Collaboration: An Ethnography of Transcript Authorization,” in Experimental Collaborations: Ethnography through Fieldwork Devices, ed. Adolfo Estalella and Tomás Sánchez Criado (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2018), 132–53.

↑ - 11

“The ERGO Years: 1977–2005,” AngloGold Ashanti (Johannesburg, n.d.), 7.

↑ - 12

Ulrich Förstner and Gottfried T. W. Wittmann, “Metal Accumulations in Acidic Waters from Gold Mines in South Africa,” Geoforum 7, no. 1 (1976): 41.

↑ - 13

Förstner and Wittmann, “Metal Accumulations in Acidic Waters from Gold Mines in South Africa,” 41.

↑ - 14

Critical debates about toxic assets have largely followed the 2008 financial crisis. Since then, the term “toxic asset” has come to designate stocks, bonds, and other securities that lack a functional market because they are based on debt, which has a high risk of default. See Melinda Cooper and Martijn Konings, “Rethinking Money, Debt, and Finance after the Crisis,” South Atlantic Quarterly 114, no. 2 (April 2015).

↑ - 15

Bremner, “Political Life of Rising Acid Mine Water,” 474.

↑ - 16

Bremner, “Political Life of Rising Acid Mine Water,” 474.

↑ - 17

Stephen Sparks, “Apartheid Modern: South Africa’s Oil from Coal Project and the History of a Company Town” (PhD diss., University of Michigan, 2012).

↑ - 18

“ERGO Years: 1977–2005,” 7–12.

↑ - 19

On the history of job restriction according to racial classifications see: Elaine N. Katz, “Revisiting the Origins of the Industrial Colour Bar in the Witwatersrand Gold Mining Industry, 1891-1899,” Journal of Southern African Studies 25 (March 1999): 73-97; Donald L. Donham and Santu Mofokeng, Violence in a Time of Liberation: Murder and Ethnicity at a South African Gold Mine, 1994 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011); Gabrielle Hecht, Being Nuclear: Africans and the Global Uranium Trade (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2014). Madeline K. Scammell et al., “Urinary Metals Concentrations and Biomarkers of Autoimmunity among Navajo and Nicaraguan Men,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17, no. 15 (July 2020): 5263.

↑ - 20

Jonathan Crush, “Scripting the Compound: Power and Space in the South African Mining Industry,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 12, no. 3 (1994): 304.

↑ - 21

Crush, “Scripting the Compound: Power and Space in the South African Mining Industry,” 304.

↑ - 22

Achille Mbembe, “Aesthetics of Superfluity,” Public Culture 16, no. 3 (Fall 2004): 377.

↑ - 23

Cooper, Life as Surplus; Thomas Lemke, “Conceptualising Suspended Life: From Latency to Liminality,” Theory, Culture & Society 4, no. 6 (2023): 69–86; Sophia Roosth, Synthetic: How Life Got Made (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017).

↑ - 24

Mazen Labban, “Deterritorializing Extraction: Bioaccumulation and the Planetary Mine,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104, no. 3 (2014): 560–76.

↑ - 25

Labban, “Deterritorializing Extraction,” 563.

↑