The Nail-House of the Sent-Down Girl: Exile and Migration in China’s Modern City

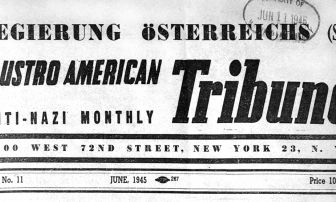

The nail-house of Caiwuwei in 2007, when it was the last village building standing on the Kingkey Tower construction site.

Illustration © Juan Du.Zhang Lianhao, a woman migrant turned villager-owner of China’s most expensive nail-house, makes a brief appearance in my 2020 book, The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City.1 In the book, I explore the Shenzhen region’s rural past and urbanization, weaving together complex social and spatial histories with personal stories of migration, success, and struggle—stories that have been obscured in the mythmaking around China’s model city. Among the dozens of Shenzhen residents featured in the book, Zhang’s relationship with the city was the most dramatic, controversial, and inconclusive. She is the protagonist of the following article, in which I have further elaborated her personal history and contextualized it within China’s national history, to foreground Zhang’s migration within a fraught history of development and displacement. The method of research has been one of recuperation, through architectural analysis, spatial mapping, analysis of historical records, policy, and Zhang’s own protest letter, interviews with those who knew her, and critical re-examination of hundreds of print and social media sources. Her story challenges our understanding of who builds, prospers, and belongs both in contemporary Shenzhen and in cities around the world.

Prologue

In 2009 in Shenzhen, a “nail-house” (dingzi hu) owned by sexagenarian Zhang Lianhao and her husband, Cai Zhuxiang, was demolished to make way for KK100, a one-hundred-story luxury commercial tower designed by British architect Terry Farrell. The term “nail-house” refers to the home of people who refuse to move out in the face of eviction notices—their houses resemble a lone, stubborn nail in an otherwise smooth wooden plank.2 Residences like Zhang’s were rented out to local workers as the Shenzhen region urbanized. While displacement caused by government policy and real-estate development were not uncommon during China’s push towards urbanization, Zhang’s long refusal to give up her property brought her intense public scrutiny, especially after she and Cai netted twelve million yuan in compensation for the demolition of their home. Zhang’s private life was splashed across regional and national news media, with most portraying her as the “greedy” owner of “China’s most expensive nail-house.”3

China’s nail-houses have attracted global attention since dramatic photographs of buildings stranded in the middle of active construction sites began to be featured in international news stories. There are currently numerous news galleries, blogs, and Pinterest pages dedicated to nail-houses, each of them featuring images of solitary buildings in the middle of newly built highways, parking lots, and construction sites.4 Architects and artists have co-opted the images and forms of China’s nail-houses for exhibitions and designs.5 However, most of the accounts in popular media neglect the hidden personal stories and specific urban histories behind nail-houses, ones that reveal how migrant women shaped urban life.

Zhang was born in Guangzhou, and in 1964, at the age of seventeen, she migrated to the village of Caiwuwei in rural Bao’an county; this village is now the site of Shenzhen’s financial district. Her relocation was part of the central government’s frenzied Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement in which, between 1962 and 1979, 29.5 million young women and men were exiled from cities to rural areas and forced to abandon their high schools and universities so they could be “re-educated” through physical labor.6 The migrants came to be known as “sent-down” youth. This movement ended in the late 1970s following large-scale protests, and most youths returned to their home cities, but Zhang was by then married to Cai, a local villager, and the mother of two children. She stayed in Caiwuwei and experienced the area’s radical transformation from a rural county of three hundred thousand into China’s model modern city of twenty million.7

During the rapid urbanization of the 1980s, Zhang owned a nongaming fang (or “peasants’ house”), the most prevalent form of housing for migrant workers in Chinese cities. By the 2000s, Zhang and Cai, like many former villagers in Shenzhen, had transformed their home into a multi-level house to generate rent and meet the needs of the city’s worker population. Zhang’s story, along with the construction, transformation, resistance, and eventual demolition of her nail-house, reflects the tenuous existence of hundreds of millions of rural migrants in China’s cities.

Fig. 1. “Nail-house,” or dingzi hu, refers to the houses of individuals who have refused to move when facing eviction notices from developers or the government. There are numerous national and international news galleries, blogs, and Pinterest pages devoted to the architectural type.

Screenshot of Google search results for “China’s ‘nail houses,’” May 19, 2021.

1. Forced Exile, Urban-to-Rural Migration

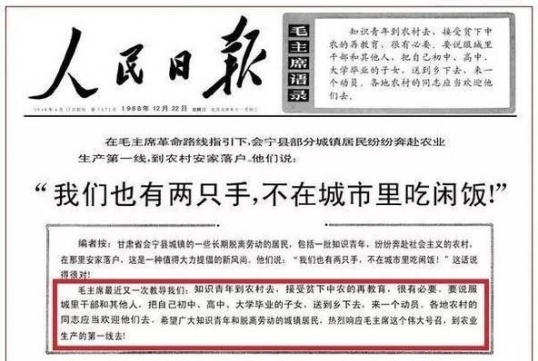

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, countless articles in China’s national and local newspapers reported on enthusiastic “educated youth” participating in the Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement. A 1965 article, published in The People’s Daily, the country’s leading national newspaper, is entitled “We too have two hands, let us not laze about in the city!” (fig. 2)8 The headline was purportedly a quotation from the youths themselves:

Many urban residents from Gansu province’s Huining county who suffer from long-term unemployment, including some educated youth, join the socialist villages and settle down there. This is a highly commendable new trend. They say, “We too have two hands, let us not laze about in the city!” This is such an agreeable quote!

In the upper right-hand corner of the page, and again within the editorial, are words taken from Quotations from Chairman Mao, the Little Red Book:

There is a need for the educated youth to go to the countryside to receive reeducation from the poor lower and middle peasants. We must persuade the urban cadres and others to send their offspring who are junior and senior middle-school and university graduates to the countryside. Comrades of the various villages ought to welcome them.

Fig. 2. An article published on December 22, 1968 in The People’s Daily was entitled “We too have two hands, let us not laze about in the city.”

ThePaper, “Naxienian, lingdaoren he gaokao de shier” (In those years, the leaders and the college entrance examination), ThePaper.cn, June 8, 2014.

The movement was initially voluntary and aimed to send young and jobless urban residents to work in rural agricultural production, but it was later escalated into a massive forced migration that exiled people from their homes and deeply impacted the entire country.9 Between 1968 and 1980, eighteen million “urban educated youths” were conscripted by the government to work in the country’s rural villages, mining fields and borderlands.10 By 1979, the movement had sent nearly thirty million people from cities to rural areas.11

When Zhang arrived, Caiwuwei was a rural village located in the borderland between China and British Hong Kong. The centuries-old village was one of the largest and most important in the area, but in the mid-1960s its inhabitants were struggling with the economic consequences of decades of war, famine, and political strife.12 Zhang joined the Red Production Team (a labor team in the village) and earned a wage of twenty-nine cents per day.13 In 1969, then twenty-two years old, she married Cai Zhuxiang and gave birth to a baby. Cai was well-liked and a skilled tractor driver. As the holder of an urban hukou, Zhang was applauded for marrying someone with a rural hukou.14

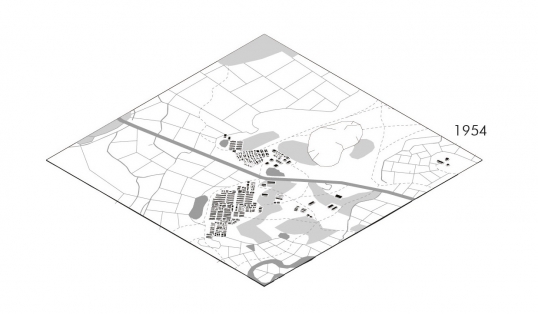

Fig. 3. Historical transformation diagram of Caiwuwei Village and its surroundings, ca. 1954.

Illustration © Juan Du.

Marriages of this kind, between villagers and sent-down youth, took place across China. In many cases, however, urban-born women complained of discrimination from villagers whose attitudes toward females were more feudal than in their home cities. Villagers’ customs and traditions contrasted sharply with the liberal, progressive values of the young outsiders, often resulting in clashes. In 1976, for instance, nearly 10,000 cases of abuse and 4,970 “unnatural deaths” among sent-down youths were reported.15 There were many reports of forced marriages and rape. The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement involved systematic physical and psychological violence alongside hard labor for all, but the situation was exceptionally difficult for women. And the victimization of women did not end at sexual abuse (which Zhang was not known to have suffered). Uprooted from their interpersonal support networks upon arriving in villages, urban women suffered a lack of basic healthcare, including sex education. One report from Jilin province noted that 70 percent of female sent-down youths suffered from “female illnesses,” caused by working in wet fields during their menstrual periods.16

Ultimately, more than half of the sent-down youths—14.9 million—returned to their home cities when permitted by the central government in the late 1970s.17 Most of the marriages involving sent-down youths resulted in divorce, but Zhang Lianhao remained in her marriage and in her village. She seems to have accepted her urban-to-rural migration.

2. Self-Exile, Transnational Migration

The poverty experienced by Zhang Lianhao and the villagers of Caiwuwei was a consequence of China’s Great Famine, which all but destroyed civic life in the country. Between 1958 and 1962, thirty-six million people died from starvation.18 Mass starvation and violence were even experienced in Guangdong, a province considered more prosperous than other regions of the country. Zhang and Cai did not have an easy life during this time. Their combined household income was less than thirty yuan (five US dollars) a month. In 1972, Zhang gave birth to a second child, which placed further strain on the young family. Like many in his situation, Cai decided to cross illegally into Hong Kong. The high rate of cross-border migration resulted from the British colony’s short-lived Touch Base Policy, in place between 1974 and 1980, which granted residency to immigrants who had family there. Once in Hong Kong, Cai obtained a work permit and later residency status. Despite the remittances he sent back to Caiwuwei, the family’s life remained difficult.

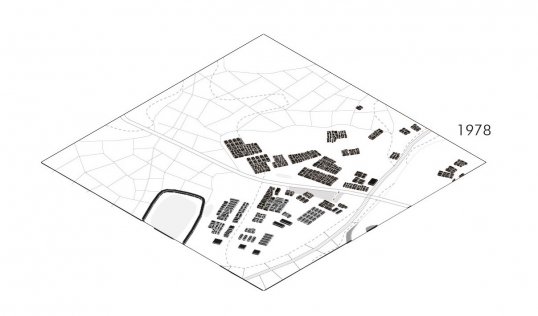

Fig. 4. Historical transformation diagram of Caiwuwei Village and its surroundings, ca. 1978.

Illustration © Juan Du.

According to villagers’ recollections, Zhang’s relationship with the community was contentious. She was seen as having an air of superiority derived from her urban roots and as not contributing enough to collective production efforts. Since her husband was her only connection to Caiwuwei, Zhang was left in the uncomfortable but not unusual position of an outsider. Women were largely expected to stay put while their husbands sought economic opportunities elsewhere. Tied down by their responsibilities as mothers, women like Zhang simply awaited their husbands’ return. The men, on the other hand, were free to be mobile or “float.” Men in Guangdong province and other parts of southern China have migrated out of the country for centuries, to Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and beyond.

In 1979, Cai Zhuxiang joined that diaspora, leaving Hong Kong with the intention of pursuing greater opportunity in the United States. However, he was smuggled onto the wrong shipping vessel and ultimately arrived in Ecuador. At first struggling to find work, Cai eventually married a local woman and had a child. After he left Hong Kong, he stopped sending remittances or letters to Zhang, making her and her children’s position even more precarious. But their lives and their village were about to undergo explosive change. Caiwuwei was one of the two thousand villages in Bao’an county designated to become the city of Shenzhen.

3. Reform and Opening, Rural to Urban Migration

The establishment of the city of Shenzhen in 1979 and the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in 1980 marked the beginning of China’s era of Reform and Opening, which eventually changed the country, the world economy, and millions of lives. The first step in the government program was to expropriate land from the various villages and townships to build a city. In 1981, SEZ policy mandated that all land within the zone was state-owned and that the private sector would have right of use but not ownership.19 A year later, the policy was applied to all village land. Under these policies, the government could expropriate land as it saw fit. In the meantime, it waived the requisition fees for residential areas of villages inside the SEZ and allowed villagers to continue to use the land.

A unique local policy, the Interim Provisions of Land Management in the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone, was approved at the thirteenth meeting of the Standing Committee of the Fifth People’s Congress of Guangdong province on November 17, 1981. It stipulated:

Article 2: The mineral resources, waters, wasteland, farmland, forests and other land and sea resources within the SEZ, whether awaiting or under development, are centrally managed by the Shenzhen Municipal People’s Government of Guangdong Province. The municipal government can carry out requisition, expropriation or nationalization of land according to the needs of development, and while observing the relevant statutes.

Article 5: Units and individuals who have secured authorization only have the right of use to the land, and not the ownership of it. Buying and selling, and disguised sales of land, as well as lease and transfer of land without authorization, are prohibited. The exploitation, use or destruction of underground resources and other resources are prohibited.

The early policies also set out the need for compensation to the village organizations and the villagers themselves:

Article 6: The requisition, expropriation or nationalization of land according to the needs of development should be compensated, by observing the relevant regulations of the People’s Republic of China and the People’s Government of Guangdong Province.

Caiwuwei was one of the first villages to be expropriated. Under a 1982 policy, each village was able to reserve land for collective industrial and commercial use. By the mid-1980s, village-operated factories emerged, augmenting Shenzhen’s industrial ambitions.20 Numerous factories built in and around Caiwuwei became magnets for migrant workers. As the government and factories could not build enough dormitory housing for the nearly daily arrivals of new migrants, the villagers satisfied some of the demand by renting out their homes.

Each village household in Shenzhen had been designated plots of between 100 and 150 square meters of home-based land (HBL), within which homes of eighty square meters in footprint and two stories in height could be built. The HBL allocation, however, was limited to male villagers, following age-old beliefs that men were the breadwinners. Women were expected to marry men with an HBL allotment. Shenzhen had become a pilot zone for experiments with market policies, but challenging the village patriarchy was not one of them.

There were, however, exceptions. For example, some village organizations assigned HBL to widows or divorcees. Zhang, perhaps lobbying for herself as a widow—she had not had news from her husband in nearly a decade—received HBL to build a simple village house. She worked multiple jobs to pay for its construction and to provide for her children. As the city grew around Caiwuwei, she began renting parts of her house to workers, eliminating the need for her to work multiple jobs. Her identity as a sent-down youth was slowly forgotten as Caiwuwei entered a new era. Instead, her identity became that of an unusual “non-villager” landlord collecting “undeserved” income from factory workers. As Shenzhen prospered, Zhang’s right to the house, the land and a place in the city were challenged.

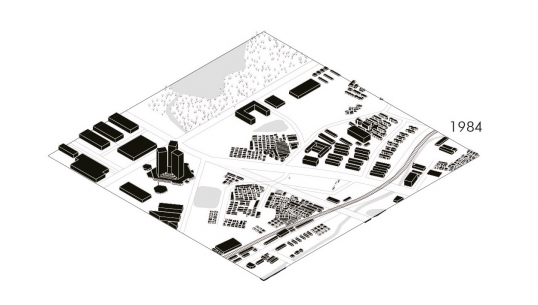

Fig. 5. Historical transformation diagram of Caiwuwei Village and its surroundings, ca. 1984.

Illustration © Juan Du.

4. Home Return Migration

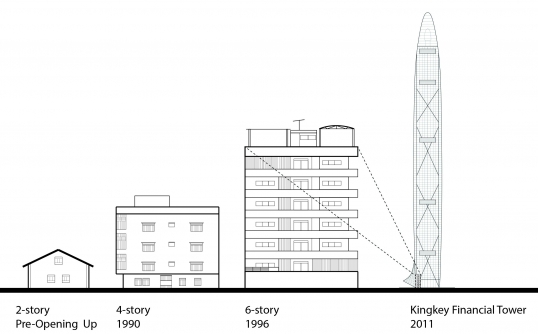

By 1988, Cai had become aware of Shenzhen’s prosperity. He decided to leave his Ecuadorian family and return to Shenzhen, to Zhang and the village house that he still officially owned.21 In 1990, a reunited Zhang and Cai added two floors to their house, only to see it dwarfed by the houses of six stories or more that sprang up around them. In the early 1990s, inhabitants of Caiwuwei formed incorporated companies, but Cai was excluded from them as he had given up his citizenship in the People’s Republic of China for Hong Kong residency.22 Despite being denied access to other sources of income, Zhang and Cai earned enough from rent to lead a relatively comfortable life.

With the rising demand for labor by village factories, village houses were packed with migrant workers. In 1992, the Shenzhen government designated all land in the SEZ, including HBL, as state-owned.23 Rental units and buildings that did not have government permits were outlawed. This policy was meant to curb the construction and operation of rental buildings, but villagers continued to believe that the land belonged to the village collective. New construction continued and escalated each year with bigger and higher buildings. The apparent disregard of the new land and property laws fueled the official narrative that urban villagers were law-breaking, unscrupulous slumlords who robbed migrant workers of their hard-earned wages. But the speed and rate of Shenzhen’s economic growth was reliant upon housing provided by the villagers, and the design and quality of housing varied both within and between villages.

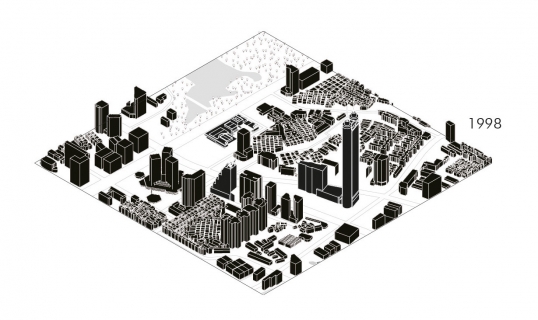

Fig. 6. Historical transformation diagram of Caiwuwei Village and its surroundings, ca. 1998.

Illustration © Juan Du.

In 1996, Cai and Zhang replaced their four-story house with a new, six-story one. Rather than following the common practice of building small, one-bedroom units, they fitted out each floor as a three-bedroom apartment, with a living room, a kitchen, and balcony. Even though the three-bedroom configuration would generate less rental income than more tightly compartmentalized housing, Cai and Zhang were proud of their relatively spacious property.24 Their house served as a viable alternative to the isolated and heavily surveilled worker dormitories in Shenzhen’s factory housing compounds.

Self-built village houses—illegal but commonplace in urbanizing China—offer a rare example of an indigenous population directly participating in the construction of a new city. This phenomenon deconstructs the widely accepted theory that Shenzhen’s success can be attributed entirely to its masterplan. The history of Zhang’s village house presents an alternative perspective on the city’s growth and reveals how the architecture of Shenzhen’s urban villages were central to modernization. The urban villagers and their towers have nevertheless long been portrayed as zang, luan, cha (dirty, messy, poor quality) and antithetical to the gleaming image the city has of itself. This stigma extends to the term “nail-house,” a stubborn object that should be forcibly pried out.

5. Urban Renewal and Evictions

In the early 2000s, a large-scale urban renewal project was launched to build the Shenzhen Luohu Financial District. As a part of the masterplan, the People’s Bank, China’s largest state-owned bank, was to expand its Shenzhen headquarters onto land occupied by Caiwuwei. The expansion comprised plans for residential and commercial developments, including a skyscraper that would become the tallest building in Shenzhen. The land requirements called for the demolition of residential and commercial structures owned by 386 village households, including Zhang and Cai’s house.25 A Shenzhen-based development company, Kingkey Group, spearheaded the project in 2004 and reached an agreement on compensation for the demolition of village property with the leaders of the Caiwuwei Village Corporation in 2006. However, most villagers were not informed of the deal and were dissatisfied with the terms of compensation. Zhang and Cai were unaware of the plans until they read about them in a local newspaper. Kingkey Group and the city government held an international design competition in 2006 for what it called the “Shenzhen Wall Street.” The urban renewal project included a record-setting skyscraper and other commercial and residential towers. Terry Farrell would win the competition for the 442-metre-tall Kingkey Tower, KK100.

Demolition of the village neighborhood started in September 2006. By October, 370 village households had signed on to the relocation agreement.26 Zhang and Cai were among sixteen families who continued to reject of the terms offered. By March 2007, six nail-houses remained. Zhang and Cai were the most active in voicing their disagreement. The couple did not trust the developer’s promise for future property as compensation and instead asked for cash payouts for equivalent-sized residential properties at the competitive market rate. Negotiations stalled when the developer’s ultimate offer was 25 percent less than Zhang and Cai’s expectations.

Fig. 7. The nail-house of Caiwuwei in 2007, when it was the last village building standing on the Kingkey Tower construction site.

Illustration © Juan Du.

Facing pressure from the developer, the government, village leaders and neighbors, Zhang and Cai turned to the press to raise awareness of their struggles. Throughout 2006 and 2007, the couple gave numerous interviews to local and national media, and the issue was widely published in newspapers. Public opinion was divided, with most people feeling that the pair should just take the money offered and clear out. On March 22, 2007, the local government office of the Shenzhen Lands Bureau ruled in favor of appeals by the developer and issued legal orders for Zhang and Cai to move out of their house within twenty days. Apparently believing that the issue was not being effectively communicated to the public, Zhang wanted people to understand her sorrows and reasoning in her own words. On March 29, 2007, she posted a passionate public letter online. It was titled “Forced Land Acquisition for the Tallest Tower in the South Makes Me Feel Helpless”:

My name is Zhang Lianhao, female, sixty years old. My current household residence is at Number 12 Old Walled Village, Caiwuwei, in Shenzhen’s Luohu District, known as the Dingzi Hu (Nail-house) of Shenzhen!

I was seventeen years old when I answered the Communist Party’s call for Educated Urban Youth to go Up the Mountain Areas and Down to the Countryside. I came from Guangzhou to the present-day Caiwuwei Village and joined the number-one Red Team to support rural development. I married an indigenous villager of Caiwuwei in 1969. In May of 1977, in accordance with a national policy, each village household was allotted land for a homestead. We built a house on the land allotted to us and after the reform and opening up of the country, our lives stabilized. However, the good times did not last forever. In 2006, land developers came in the name of remodeling villages in the city to target our village for construction development. They did not put the villagers’ interests first, but rather aimed to profit from land acquisition and sales. The land developers, who had the support of the regional government, flaunted their tough attitude and emphatically expressed their insistence on negotiating with me in a high-handed fashion, stating our property would be acquired at a far lower value than the surrounding properties. The arbitrary terms included “a compensation at the rate of 6,500 yuan per square meter,” or “a one-to-one area house of unknown structure and quality to move back into in four years,” “no compensation for balcony or roof garden,” and “no homestead land compensation.” While the surrounding properties were valued at sixteen thousand yuan or higher per square meter, my seven-story single-family house in the solid, bright, beautifully decorated villa style, with permanent land use rights, was valued by the land developers at only three thousand yuan per square meter! My homestead land (usage rights) would be given away for free, without a single penny of compensation! Being just a plain citizen, how can I even think of fighting the government?!

I just want to be able to live and work in peace. The Communist Party’s Reform and Opening Up policies provided me with a happy life, but now this happiness is being destroyed by land developers. Such unfair terms of compensation, how can I accept them?!

During this time, land developers, district government, sub-district office, village committee and task forces were calling upon us non-stop. Even the requisition office under the land bureau had summoned me twice to answer to a ruling, threatening to proceed with forced demolition once the ruling took effect! When they saw I did not give up, they proceeded to harass me: cutting off water and power supply for seven months, blocking traffic passages, disconnecting the telephone line and cable TV. After the developers had put up a wall around the demolition site and placed guards at the gate, they would repeatedly send someone to defecate in the front and back of our house. I called the local police seven times to no avail. Being in my sixties with a weak heart, these hurtful acts lead to my frequent loss of consciousness and needing resuscitation.

I am a Chinese citizen protecting my legal rights and trying to lead a peaceful life. Am I wrong in choosing to do so? Do they mean to hound me to death?

Her letter was quickly circulated online and most local news media outlets also carried the story. Public opinion, however, remained on the side of the developer and the government. Online and in print, Zhang’s letter and plea were met with criticism and ridicule. The amount of compensation demanded by Zhang and Cai was deemed unreasonable and undeserved. But Zhang and Cai remained undeterred. They read up on China’s property law and ultimately discovered a statute that ensures equal protection to owners of both public and private properties. When the Lands Bureau eviction order was issued in May, the couple took the government to court. In the meantime, the real estate market around Caiwuwei had skyrocketed. Well-informed of the law and the stakes, Zhang and Cai raised their asking price further, to eighteen thousand yuan per square meter—a total compensation of fourteen million yuan, a staggering price. In mid-August, when the Shenzhen Luohu District Court ruled again in favor of an eviction, Zhang and Cai and two other nail-house families locked themselves inside their homes and prepared to be bulldozed with their houses. Then, suddenly, the Chinese Ministry of Lands and Resources in Beijing issued a national order to stop all eviction processes across China.27 The developer and local government subsequently reached a compromise with Cai and Zhang, signing the relocation agreement for twelve million yuan. On October 22, 2007, the most expensive nail-house in China was demolished.28

Fig. 8. Evolution of the Caiwuwei nail-house from the 1980s to its final six-story incarnation in 1996 and eventual replacement by the one-hundred-story tall Kingkey Tower.

Illustration © Juan Du.

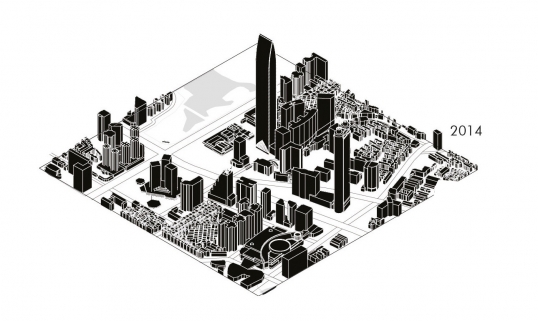

Fig. 9. Historical transformation diagram of Caiwuwei and its surroundings, ca. 2014–present.

Illustration © Juan Du.

Postscript

After the house was demolished, Zhang disappeared from the public eye. The media searched for her and interviewed Cai and their former neighbors, but she had vanished. There were press stories about disagreements between Zhang, Cai, and their children over how to use the compensation money. The apparent outcome was marital separation, and Cai was alleged to have moved to the periphery of Shenzhen with a mistress.

A search in public records of her Hong Kong identity number (which was published in news reports) led to results of “ID canceled.” This normally indicates that the person has died or has voluntarily withdrawn it—a rare step for a Chinese citizen to take. While Zhang’s whereabouts remain uncertain, Caiwuwei assumed a second life, with the KK100 tower breaking ground on November 11, 2007. By year’s end, Caiwuwei’s total net assets were estimated at 68.7 million yuan, its yearly revenue at over 140 million yuan, and its total tax paid to the government at over 10 million yuan.29 The village’s collective and individual assets had increased dramatically, and the process was widely lauded as a successful template for community relocation. The “Caiwuwei model” came to be known as the method to follow for the redevelopment of urban villages across China.

Zhang, however, had been exiled and displaced again. This was her second reverse migration. While nearly all media coverage of her pointed out how much she benefited financially from Shenzhen’s urbanization, the fact that she was a two-time victim of forced exile—first through the sent-down movement and again because of urban renewal—was never acknowledged. Zhang’s unwillingness to negotiate with the village corporation reflected her experience as an outsider—not only to the city but also to the village—as a “sent-down” woman and as a widow (for ten years). Her complex identities compounded her distrust of the village as a patriarchal institution. Her repeated rejection of compensation can be interpreted as a way for her to reclaim fair treatment. The nail-house was the material embodiment of years of personal effort and socio-political struggle, her physical claim in the city.

Zhang may have been exceptional in her outspokenness and perseverance, but her struggles were by no means an exception. Her personal history reflects the tenuous urban existence of hundreds of millions of rural migrants in China’s rapidly urbanized cities. It offers a rare glimpse into the largely untold and unexamined present-day consequences of China’s sent-down movement as well as the widespread evictions of building owners and renters. Zhang’s personal narrative provides an allegory of the city’s history and symbolizes the massive changes that took place in China during the tumultuous decades around the turn of the century. Was Zhang’s disappearance an act of self-exile from civic society, from a public and press that she believed (with good reason) would be unsympathetic? Or was it a form of self-preservation after a lifetime of hardship and dissent? In the story of Shenzhen’s urbanization, Zhang is both unique in her defiance of unstoppable forces and emblematic of the many people displaced by them. She is as much a part of the city’s narrative as its gleaming towers.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Juan Du, “The Nail-House of the Sent-Down Girl: Exile and Migration in China’s Modern City,” Aggregate 10 (November 2022), https://doi.org/10.53965/INEO8962.

- 1

Juan Du, The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2020).

↑ - 2

Howard French, “Homeowner Stares Down Wreckers, at Least for a While: One Women Is an Island,” New York Times, March 27, 2007. Zhiling Huang, “We Are Not Going Anywhere,” China Daily, March 31, 2007.

↑ - 3

Jianfeng Fu, “’Zuigui dingzi hu’ huo buchang yu qianwan quanli huifou bei lanyong” (“The most expensive nail house” was compensated with over ten million: Will the power be abused?), Southern Weekly, October 18, 2007.

↑ - 4

See keyword search of “China’s Nail Houses” in Google: https://www.google.com/search?q=China%27s+nail+house&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiYg6vCyonxAhWBLqYKHc9-DuMQ_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=680&bih=409.

↑ - 5

“Chongqing’s ‘Nail House’ about to Fight its Last Battle in Zurich,” Architecture, Venice Biennale, September 24, 2010, https://we-make-money-not-art.com/thomas_demand/. Caruso St. John Architects, “Nagelhus: In Collaboration with Thomas Demond, Zurich, Switzerland, 2007–2010,” https://carusostjohn.com/projects/nagelhaus/#more.

↑ - 6

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, “The Number of China’s Send-Down Youths,” in China Labor Wage Statistics (Beijing: China Statistics Press, 1986). Yiran Pei, “’Zhiqing xue’ ji dacheng zhizhu” (A comprehensive work on educated youth), Twenty-First Century 121 (2010).

↑ - 7

Du, The Shenzhen Experiment.

↑ - 8

“Naxienian, lingdaoren he gaokao de shier” (In those years, the leaders and the college entrance examination), ThePaper.cn, June 8, 2014, https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_1249691.

↑ - 9

Yizhuang Ding, Zhongguo zhiqing shi: chu lan, 1953–1968 nian (A history of Chinese educated youth: the beginning, 1953–1968) (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 1998). Xiaomeng Liu, Zhongguo zhiqing shi: dachao, 1966–1980 nian (A history of Chinese educated youth: its peak, 1966–1980) (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 1998). Xiaomeng Liu, Zhongguo zhiqing koushu shi (An oral history of Chinese educated youth) (Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2004).

↑ - 10

Michel Bonnin and Krystyna Horko, The Lost Generation: The Rustication of China’s Educated Youth (1968–1980) (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2013).

↑ - 11

National Bureau of Statistics of the People’s Republic of China, “The Number of China’s Send-Down Youths.”

↑ - 12

Du, “Nail House on ‘Wall Street,’” in The Shenzhen Experiment, 202–206.

↑ - 13

Yi Song and Xiaopeng Chen, “Luohu cunzhuang 60 nian zhi Caiwuwei” (60 years of villages in Luohu, Caiwuwei), Yangcheng Evening News, September 2, 2009. Jie Tang, “5 nianqian huopei 1700 wan Shenzhen ‘Zhongguo zuigui dingzi hu’ jin hezai” (“China’s most expensive nail household” received 17 million RMB in compensation five years ago, Where are they today in Shenzhen?), Jing Bao, November 1, 2012.

↑ - 14

Under Mao’s Household Registration System, enacted in 1958, at birth every citizen is assigned a registration hukou designating the location of their residence. Goods and services are subsequently collected and distributed to the registered population in each province’s cities and villages.

↑ - 15

Xiaomeng Liu, Zhongguo zhiqing shi: dachao, 1966–1980 nian.

↑ - 16

Xiaomeng Liu, Zhongguo zhiqing shi: dachao, 1966–1980 nian, 47.

↑ - 17

National Bureau of Statistics of the People Republic of China, “The Number of China’s Send-Down Youths.”

↑ - 18

Jisheng Yang, Tombstone: The Great Chinese Famine, 1958–1962, translated by Stacy Mosher and Jian Guo (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2012). Xizhe Peng, “Demographic Consequences of the Great Leap Forward in China’s Provinces,” Population and Development Review 13, no. 4 (1987): 639–670. Ansley J. Coale, “Population Trends, Population Policy, and Population Studies in China,” Population and Development Review 7, no. 1 (1981): 85–97. Jasper Becker, Hungry Ghosts: Mao’s Secret Famine (London: John Murray, 1996). Penny Kane, Famine in China, 1959–61: Demographic and Social Implications (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1988). Basil Ashton and Kenneth Hill, “Famine in China, 1958–1961,” Population and Development Review 10, no. 4 (1984): 613–645. Carl Riskin, “Seven Questions about the Chinese Famine of 1959–61,” China Economic Review 9, no. 2 (1998): 111–124. Felix Wemheuer, “Sites of Horror: Mao’s Great Famine,” The China Journal 66 (2011): 155–164.

↑ - 19

Shenzhen Municipal Government, “Shenzhen jingji tequ tudi guanli zanxing guiding” (Interim provisions of land management in the Shenzhen special economic zone) (Shenzhen, 1981).

↑ - 20

Lei Feng, “Shenzhen Huaerjie ruhe tuwei?” (How can Shenzhen’s ‘Wall Street’ stand out?), Nanfang Metropolis Daily, January 12, 2010.

↑ - 21

Tang, “5 nianqian huopei 1700 wan Shenzhen ‘Zhongguo zuigui dingzi hu’ jin hezai.”

↑ - 22

Feng, “Shenzhen Huaerjie ruhe tuwei?”

↑ - 23

Shenzhen Municipal Government, “Shenzhen jingji tequ fangwu zulin tiaoli” (Bylaws of rental housing in the Shenzhen special economic zone) (Shenzhen, 1992).

↑ - 24

Du, “Nail House on ‘Wall Street,’” 195–231.

↑ - 25

Tang, “5 nianqian huopei 1700 wan Shenzhen ‘Zhongguo zuigui dingzi hu’ jin hezai.” Zhongyu Zhang and Kaiwen Zhong, “Zouxiang shendu chengshihua de duoyuan lujing: Shenzhen tudi erci kaifa moshi tanxi” (Towards deep urbanization with multiple paths: analysis of mode of land redevelopment in Shenzhen), The Chinese Newspaper of Land and Resources, May 22, 2015.

↑ - 26

Fu, “’Zuigui dingzi hu’ huo buchang yu qianwan quanli huifou bei lanyong.”

↑ - 27

Ministry of Land and Resources of the PRC, Guotu ziyuanbu yaoqiu gedi guifan chengzhen jianshe yongdi he guagou shidian (The Ministry of Land and Resources of the PRC requires that all municipal governments regularize urban land development and link to pilot projects), August 16, 2007, http://www.gov.cn/gzdt/2007-08/16/content_718644.htm.

↑ - 28

Du, “Nail House on ‘Wall Street,’” 195–231.

↑ - 29

Lianggang Yuan, Xiaorong Dai, and Guan He, “Caiwuwei: gu cunluo biancheng jinsanjiao” (Caiwuwei: an ancient village becomes a “golden triangle”), Shenzhen Special Zone Daily, December 23, 2008.

↑