Introduction: Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter is an ideological and political intervention in a world where Black lives are systematically and intentionally targeted for demise. It is an affirmation of Black folks’ contributions to this society, our humanity, and our resilience in the face of deadly oppression.

—Alicia Garza, “A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement”1

What does it mean to put Black lives at the center of our thinking about architecture and its history? How do architecture and urban design contribute to violence against black people? How can the tools and knowledge of our disciplines prompt change? Inspired by the scholars, activists, and everyday citizens who have spoken out, marched, and protested against police killings of African-Americans, we present this collection of short essays that directs architectural research to the Black Lives Matter movement.2

Racism fundamentally shapes architectural and urban spaces. Ta-Nehisi Coates’ devastating Case for Reparations outlines the ways in which Black Americans have been dispossessed of land, excluded from homeownership, and impoverished by redlining and predatory lending from the Jim Crow era to the recent Great Recession.3 As Darnell Moore has argued, in cities ravaged by both predatory lending and gentrification, “Black people will continue to be treated as something other than human as whiteness continues to function as a sign for possession and asset.”4 One hundred and fifty years after the end of the Civil War, houses and subdivisions remain architectural instruments in racialized practices of investment, financing, ownership, maintenance, monitoring, and tenancy. In these and other ways, architecture and urban design in the United States today too often support white supremacy, which we understand, following George Lipsitz, to include “a system for protecting the privileges of whites by denying communities of color opportunities for asset accumulation and upward mobility.”5

These links between race and space have long been visible in lived experience, and they have been addressed in architectural scholarship.6 But as architect Mitch McEwen has argued, the necessity of an architectural critique of new forms of segregation became undeniably urgent after George Zimmerman killed Trayvon Martin in the Retreat at Twin Lakes, a gated community in Sanford, Florida.7 Because they privatize formerly public functions and spaces, gated communities exemplify neoliberal approaches to housing, and some commentators were quick to identify their role in Martin’s death.8 Yet as McEwen and others have made clear, Martin’s death can not be pinned on form; rather, it must be understood as the result of intersecting spatial, legal, and social operations. Such violence against people of color requires architectural analysis, but architecture cannot account for it alone.

After the killings of Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Kimani Gray, Tamir Rice, and too many others, the vulnerability long experienced by black people in public spaces challenged the legitimacy of the state, even for those protected by white privilege. Streets, sidewalks and playgrounds such as those where Brown, Garner, Gray, and Rice died are sites where racially-biased policing governs access to liberty and life itself. Over the past year, they have been reclaimed through demonstrations, die-ins, teach-ins, boycotts, Black brunches, and “Blackout Fridays.”9 These spaces have also become sites for design interventions that make sites of violence safe for people of all colors.

While responses to this crisis of space and state can untangle, critique, and resist the conditions that have made Black life too precarious in the United States, recent protests and design projects make clear that architectural responses to the Black Lives Matter movement must also activate the aesthetic dimension of architecture, a dimension that offers resources to sustain alternative visions of Black life.10 This collection of brief essays thus comprise a mixture of aesthetic, critical, historical and theoretical analyses which we have grouped into three categories. The first essay group, Diagnosis: Policing and Incarceration, describes the architectural origins and human effects of racially-biased policing, the “school-to-prison pipeline,” and mass incarceration, identifying ways in which design has helped to create the present crisis. In Resistance: Rights to the City and Suburb, contributors outline forms of resistance developed by black people and their allies through activism, protest, research, and analysis. The third set of essays, Aesthetics: From Cities to Curricula, illuminates architectural practices that figure and reimagine Blackness through a variety of aesthetic, educational, and formal practices.

When we put out our call for contributions, we aimed to highlight work underway on this topic, as well as to spur further scholarship and reflection on the biopolitical and architectural questions raised by the Black Lives Matter movement. Time was of the essence: We hoped that this writing might nourish political conversations, and that it could be used in seminars and teach-ins this spring semester. We are very grateful to all our contributors for putting this project on the front burner, and for writing and editing so quickly and diligently. As a result of their efforts, the work gathered here directs a wide range of scholarly and activist insights toward the present crisis. But it raises as many questions as it answers, and only begins to encompass the possible responses to the Black Lives Matter movement. We invite you to deepen the discussion by commenting on the work presented here using the links at the end of each essay. We also welcome further proposals for work in a variety of lengths and formats ranging from short photo, video, sound, or text essays to long-form scholarly articles for peer review.

Diagnosis: Policing and Incarceration

Is “Justice Architecture” Just? • Raphael Sperry

Schools and Prisons • Amber Wiley

Fair Policing for the Fair City? • Researchers for Fair Policing

Defensible Space and the Open Society •Joy Knoblauch

Designing the Great Migration • James D. Graham and Michael Abrahamson

Our first five contributions diagnose how theories and practices of architecture and urban design participate in racialized sorting, controlling, and conditioning of Black life, situating aggressive police tactics within a complex of ideas, environments, and practices through which the state and other institutions exercise biopolitical control over black people.

Mass incarceration of young African-Americans is at the heart of this complex of control. The United States imprisons its population at the world’s highest rate, as Michelle Alexander has described in The New Jim Crow.11 Present-day practices of exclusion and segregation through incarceration, Alexander argues, are updated versions of the segregation laws, racial exclusions, and lynchings that maintained white supremacy in the American South from the Civil War to the Civil Rights movement. Architects not only have participated in and profited from the incarceration complex, but also have fueled it intellectually and materially, as contributors to this section make clear. And yet architectural analysis has also been turned against incarceration. As Laura Kurgan and Eric Cadora so notably showed in Million Dollar Blocks, redirecting state expenditures for incarceration to the neighborhoods from which prisoners originate would support extensive physical improvements and social services, reducing both crime and the violence that incarceration inflicts on individuals, families, and communities. Their proof that mass incarceration is fiscally wasteful exposes the racism and classism inherent in the contemporary prison system.

Architecture intersects mass incarceration most directly through the design of police stations, courthouses, jails, and prisons. The opening essay in this section, “Is ‘Justice Architecture’ Just?,” by Raphael Sperry, president of Architects, Designers, and Planners for Social Responsibility, considers the design and designers of the Ferguson, Missouri Police Station. Noting the difference between how the project is received in the architectural community and in the world at large, Sperry argues for architects to follow standards of justice articulated in international human rights charters, and calls on us to refuse commissions to design execution chambers and spaces for prolonged solitary confinement.

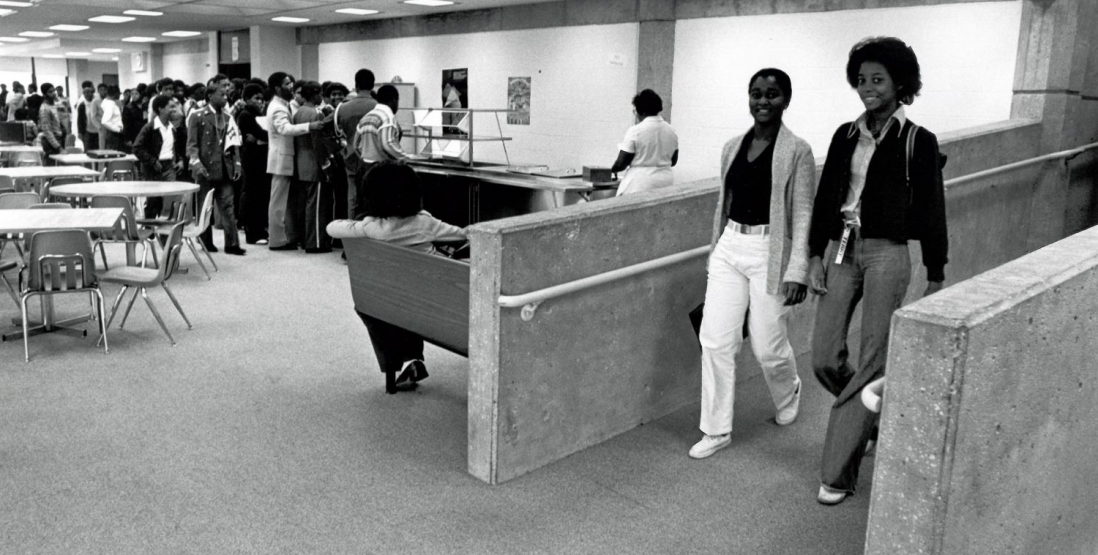

Mass incarceration extends beyond prisons and courthouses to shape the design and use of another architectural type central to contemporary biopolitics: the school. In her essay “Schools and Prisons,” Amber Wiley traces the successive renovations of the Dunbar High School in Washington, D.C., as it shifted from a Brutalist building that promoted autonomy and self-control via open plans to a contemporary facility that emphasizes surveillance and security screening. Wiley develops a historical framework for understanding how architects build what has come to be called the “school-to-prison pipeline”: the disciplinary practices in education that set the stage for mass incarceration.

Intrusive screening and intervention are too often daily realities for young people of color. In “Fair Policing for the Fair City?,” Researchers for Fair Policing, an intergenerational organization that links youth and academic researchers, present four video testimonials in which young people of color in New York City describe their experience of policing and its impact on their lives. These narratives offer perspectives on two approaches to policing that have marked the past decades in New York and elsewhere: “stop-and-frisk,” in which officers routinely interrupt daily life to question and frisk people on the streets and in school hallways, particularly in majority-minority neighborhoods, and “Broken Windows” policing—the tactic used in Eric Garner’s arrest—in which officers pursue and punish minor infractions, such as vandalism or subway fare evasion, on the theory that maintaining order at the small scale reduces more serious forms of lawlessness. These approaches, the videos suggest, have extended the incarceration complex well beyond prisons into other public spaces, creating a world in which self-surveillance and fear dissolve distinctions between public and private life.

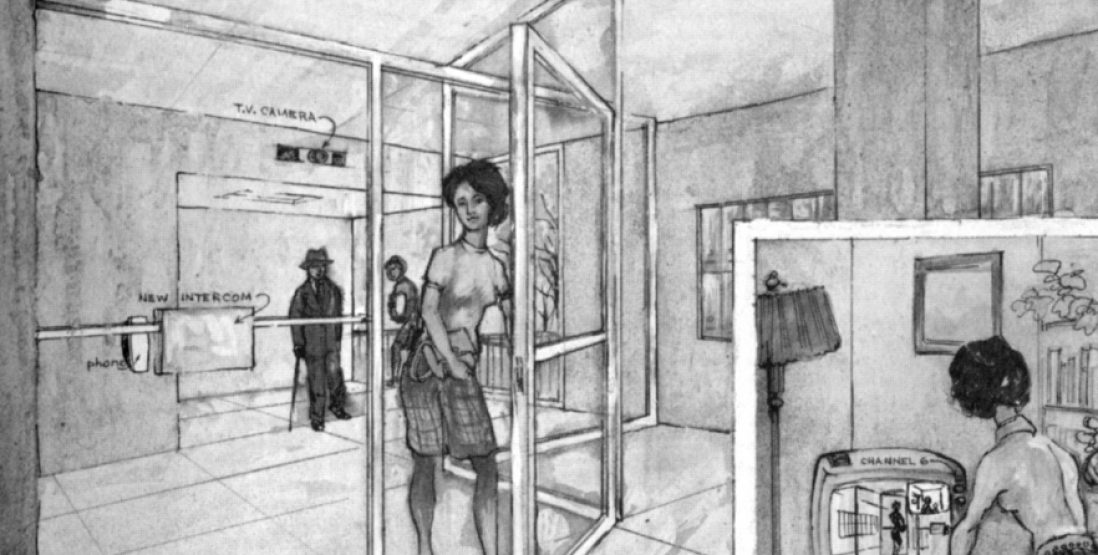

Police tactics such as Broken Windows policing may seem to be outside of the realm of design, but their intellectual origins lie at least partially in architectural discourse. Joy Knoblauch’s essay “Defensible Space and the Open Society” focuses on the theory of “defensible space” put forward by architect Oscar Newman in the late 1960s. Newman imagined that well-designed public spaces and resident self-surveillance could solve social problems by creating a self-policing open society. His belief that maintaining physical order is crucial to maintaining social order was highly influential to the original theorists of Broken Windows policing strategies. And yet the liberal ambitions of Newman’s theories–to create a society that required less outside policing–were jettisoned as Defensible Space theory was operationalized in order maintenance policing. Recuperating Newman’s ambitions while pointing to the paradoxes of the exercise of power in liberal societies, Knoblauch reminds us that the outcome of architectural ideas depends less on their intentions than on their implementation in a matrix of policies and practices.

Valuing Black lives pushes us to take the lived reality of architecture as seriously as we do the field’s discourse: for instance, to assess modernist cruciform towers as they were implemented by housing agencies and inhabited by working- and middle-class families, rather than as they were projected by Le Corbusier in the Ville Radieuse. In their essay “Designing the Great Migration,” on the master plan and buildings that architect Gunnar Birkerts completed for Tougaloo College in Mississippi in the 1960s, James D. Graham and Michael Abrahamson explore the intentions and outcomes of the architect’s campus design principles. Birkerts hoped to prepare rural Black students for their anticipated integration into the cosmopolitan society of industrial northern cities as part of the Great Migration, and calibrated the design of his dormitories to generate a form of integrated urbanity on the historically Black Tougaloo campus. Drawing on the work of Isabel Wilkerson and the testimony of Tougaloo alumna Gwendolyn Hayes, Graham and Abrahamson suggest that this strategy belied the pervasive segregation that graduates found in the North.12

Taken together, these essays describe a society in which soft power and police tactics intertwine in increasingly virulent ways; where discipline doesn’t replace punishment but rather supplements it; and where the biopolitics of race pervades streets and schools, houses and prisons, leaving almost no space exempt from policing. The work in this section also reminds us—as members of Aggregate argued in our book Governing by Design—that architecture operates alongside and through fields such as economics and finance, urban studies and management, politics and bureaucracy. Nowhere is this clearer or more pressing than in the system of mass incarceration.

Resistance: Rights to the City and Suburb

The Invisible Brother with a Brick • Brian Goldstein

Race, Planning, and the American City • Joseph Heathcott

The Rights to the Suburb • Dianne Harris

Air and the Politics of Resistance • Derek R. Ford

Architects and architectural discourse have helped to build systems of segregation and control such as the prison, the school, and contemporary policing, but they can also help to take apart such complexes of control. The essays in this section read space through the lens of race in order to write new accounts of resistance.

The first two contributions examine structural racism in the history and theory of cities and suburbs. Over the past few decades, historians of planning and urbanism have put race at the center of their research on cities. Outlining the development and summarizing the insights of this scholarship in his essay “Race, Planning, and the American City,” Joseph Heathcott provides context and models for the discipline of architectural history, which has been slower to recognize the constitutive role of race in American architecture.

Drawing from this literature in urban history, as well as from archival and architectural research, Brian Goldstein’s essay “The Invisible Brother with a Brick” examines urban redevelopment, riots, and resistance in Newark during the late 1960s. While the Newark riots brought much destruction to the city, they also generated powerful forms of opposition to top-down redevelopment schemes that disproportionally targeted Black neighborhoods. In Goldstein’s analysis, the brick—the raw material of Newark’s urban renewal schemes—is both a symbol and a generator of community empowerment.

As Goldstein and Heathcott make clear, urban uprisings have emblemized Black resistance to expropriation, exclusion, and displacement since the Civil Rights era. But suburban rebellions like those we have witnessed in Ferguson pose representational problems to both scholars and a public accustomed to situating riots in urban space. In “The Rights to the Suburb,” Dianne Harris suggests we develop a Lefebvrian theoretical lens for examining North American suburban uprisings. Henri Lefebvre’s work, which derives from his understanding of French suburbs as sites of exclusion, might help us better account for the racial and economic geographies of inner ring suburbs and the spatial dimensions of suburban protest.

As protesters across the United States echo Eric Garner’s dying words, “I can’t breathe,” they foreground questions about life and access to resources that are at the heart of the Black Lives Matter movement. Derek R. Ford’s essay “Air and the Politics of Resistance,” which closes this section, closely reads Garner’s words and the slogans that have spun off from them to show how activists mobilize air as a resource through which a form of a public can assert embodied rights to the very conditions of life. In the protest cultures of May 1968, pneumatic and inflatable structures were signs of youthful contestation, and air was a symbol of flexibility and freedom.13 Today, air retains that optimism but also takes on a more ominous cast. Ford argues that the biopolitical dimensions of air constitute a “pneumatic common” that defines the ground for contemporary struggle.14 Yet, he and other contributors to this section make clear that not only the air–but also the insights and creativity of activists breathing it–are invaluable resources for architectural history and theory.

Aesthetics: From Cities to Curricula

Black Spaces Matter • Charles Davis II

Toward a Black Formalism • Darell W. Fields

Farming the Revolution • Mike Carriere, Antoine Carter, and Fidel Verdin

Valuing Black Lives Means Changing Curricula • Héctor Tarrido-Picart

Making Black lives matter means looking at architecture and its history from perspectives that are often at the margins of professional and academic thinking, as when we approach Monticello and Mount Airy from cellars, kitchens, and dependencies rather than making straight for the front door. We do Black architects and creators an injustice, however, if we frame our discipline’s relevance to Black lives solely in the terms of social history. Valuing Black lives also encompasses Black aesthetics, such as the early 20th century classical revival as it was practiced by Vertner Woodson Tandy on behalf of Madam C. J. Walker or the buildings designed by Robert M. Taylor at Tuskegee Institute. It means visiting sites of African American memory with Craig Evan Barton and detouring from the main exhibition halls at a World’s Fair to visit the Negro Building with Mabel Wilson. It means understanding the profession through the experience of pioneers such as Norma Sklarek and recognizing the forms of architectural agency exercised by others outside professional practice, from philosopher W.E.B. Dubois to poet June Jordan.15

Jordan is a particularly potent reminder of the power of creative re-appropriation. She engaged architecture through writing by projecting forms and spaces of Black self-realization. In “Black Spaces Matter,” Charles Davis II describes the alternative architectural modernism that Jordan constructed from her experience in Harlem as well as from the work of Adolf Loos, Mies van der Rohe, and Buckminster Fuller. Similarly, in “Toward a Black Formalism,” an excerpt from the forthcoming second edition of his book Architecture in Black, Darell W. Fields projects an alternative modernism of his own.16 Fields, who founded Appendx, a key journal of African-American architectural theory, locates an aesthetic ground for race-based subjugation in Immanuel Kant’s aesthetic disparagement of Blackness. Yet he also makes Kant’s aesthetics a resource for architectural theory, calling on a Black “racial/spatial subject” to create a Black Formalism and a Black Architectonic by claiming the space created by its own negation.17

The world-making projects described by Davis and projected by Fields find a counterpart in the community gardening initiatives discussed by Mike Carriere, Antoine Carter, and Fidel Verdin in “Farming the Revolution.” In Carter and Verdin’s two urban gardening projects in Milwaukee, developed in part as memorials to young people who died as a result of urban violence, growing food is simultaneously a means of claiming space, a technique of psychological and nutritional healing, and a means of aesthetic expression.

The essay that closes this collection, Héctor Tarrido-Picart’s “Valuing Black Lives Means Changing Curricula” challenges educators to deepen our engagement with Black Aesthetics. Writing in response to discussions at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, where he leads the African American Student Union, Tarrido-Picart argues that architecture schools and educators can best intervene in the current crisis by teaching, writing about, researching and taking pleasure in these aesthetics. Along with David P. Brown, Sekou Cooke, and others, Tarrido-Picart sees in jazz and hip-hop the models for a distinctly African-American aesthetic and formal practice, one that offers a necessary corrective to seeing Black life only through the lens of crisis or social justice.18 “#BlackLivesMatter,” Tarrido-Picart writes, “but so does Black culture.”

Black Futures

As Tarrido-Picart suggests, educators can put Black lives at the center of our work on architecture by approaching teaching and learning in new ways. We need to write syllabi that address the issues outlined in the preceding essays, so that our courses engage more deeply with African-American histories, theories, cultures, and designs. Much current design pedagogy privileges the cultural knowledge and habitus of privileged students in its selection of building types and programs.19 From an institutional and structural perspective, we must also address the composition of our field; it has long been clear that the requirements of architectural education–its high cost, time to degree and licensure, and time commitment relative to remuneration and cultural capital–skew the demographics of our student population.

Historians and theorists can put Black lives at the center of our work in a number of ways, as the essays in this collection make clear. Most obviously, we need to find archives and write texts that include the voices and experiences of people historically excluded from the narratives of our field. We can also deepen interdisciplinary collaborations, for no single realm of study can account for the present crisis. We should revise our accounts of how power operates in buildings and cities to reflect the conditions of present-day policing and imprisonment. The biopoliticization of policing and the introduction of profit and data-driven analytics into police tactics have produced forms of regulation less visible but no less insidious than that of their precursors. Architectural theory should untangle and resist these operations of power, and we look forward to more work that takes on this task.

In galvanizing people to action, the Black Lives Matter movement has been a framework for manifesting “Black excellence,” as Patrisse Cullors puts it: for drawing out the sustained clarity, passion, and leadership of African-American activists, intellectuals, and citizens. As we launch this project, we hope that Aggregate can expand the range of venues for manifesting Black excellence and cultivating essential conversations about race.

✓ Not peer-reviewed

Jonathan Massey, Meredith TenHoor, and Sben Korsh, “Introduction: Black Lives Matter,” Aggregate 3 (March 2015), https://doi.org/10.53965/CYMM9302.

- 1

Alicia Garza, “A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement,” BlackLivesMatter.com, December 6, 2014.

↑ - 2

Black Lives Matter is one of many recent movements that have emerged in response to non-indictment of police officers responsible for the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner, and to outrage over the deaths and incarceration of too many others. We’ve chosen to align ourselves with this particular movement and slogan because its emphasis on life, biopolitics, and race resonates with our own research commitments.

↑ - 3

Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Case for Reparations,” The Atlantic, June 2014. See also Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The Racist Housing Policies that Built Ferguson,” The Atlantic, October 17, 2014; and Beryl Satter, Family Properties: How the Struggle Over Race and Real Estate Transformed Chicago and Urban America (New York: Picador, 2010).

↑ - 4

Darnell L. Moore, “The Price of Blackness: From Ferguson to Bed-Stuy,” Truthout, September 4, 2013.

↑ - 5

George Lipsitz, The Possessive Investment in Whiteness: How White People Profit from Identity Politics, rev. and expanded ed. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2006), viii.

↑ - 6

See in particular the following: Mabel O. Wilson, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums (Berkeley: University of California, 2012); Dianne Harris, Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America (University of Minnesota, 2012); (see also also John Harwood, “Review of Little White Houses,” Traditional Dwelling and Settlements Review 25, no. 2 (Spring 2014): 83); Craig L. Wilkins, The Aesthetics of Equity: Notes on Race, Space, Architecture, and Music(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007); Darell Wayne Fields, Architecture in Black: Theory, Space and Experience (London; New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Press, 2000); Cornel West, “Race and Architecture,” in The Cornel West Reader, (Basic Books, 1999) [and also Charles Davis, “Looking for Inspiration: (re)reading Cornel West’s essay ‘Race and Architecture’” (Race and Architecture blog, 2013)].

Our own work has attempted to make race a central part of architectural and urban analysis. See Jonathan Massey, “Five Ways to Change the World,” in Where Are the Utopian Visionaries? Architecture of Social Exchange, ed. Hansy Better Barraza (Pittsburgh: Periscope Press, 2012); and Rosten Woo and Meredith TenHoor with Damon Rich, Street Value: Shopping, Planning and Politics at Fulton Mall (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2010).

↑ - 7

Mitch McEwen, “What Does Trayvon’s Shooting Mean for Architects and Urbanists,” The Huffington Post, March 30, 2012. See also Dianne Harris, “Race, Space, and Trayvon Martin,” SAH Blog, July 25, 2013; and Mimi Zeiger, “Koolhaas May Think We’re Past the Time of Manifestos, But That’s No Reason to Play Dumb,” Dezeen, December 12, 2014.

↑ - 8

For two of the most popular critiques of the gated community, see Edward J. Blakely and Mary Gail Snyder, Fortress America: Gated Communities in the United States (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1997) and Mike Davis, City of Quartz (London: Verso, 1990). Writers have recently levied these critiques toward Martin’s case. See Anna Kats, “Guilty as Charged? Urban Planning and the Death of Trayvon Martin,” BlouinArtInfo, September 4, 2013; and Kelly Chan, “Trayvon Martin: Victim of Poor Urban Planning?,” Architizer, April 17, 2012. Reinhold Martin offers a more nuanced assessment in “Fundamental #13: Real Estate as Infrastructure as Architecture,” Places, May 2014. See also Richard Rothstein’s “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles,” Economic Policy Institute, 2014.

↑ - 9

A number of dynamic coalitions have emerged since November 2014. In New York, we’ve been particularly inspired by the group POC 4 Solvency, who have transformed the city’s public spaces with frequent die-ins, and who invoke human rights law to demand solvency for people of color.

↑ - 10

Darnell Moore also highlights the racial dimensions of gentrification, observing that we must look at police brutality in the larger context of “the precarious structural conditions restricting Black life from Ferguson to Flatbush, Brooklyn.” See Moore, “The Price of Blackness.”

↑ - 11

See Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: New Press, 2012). See also Alice Goffman, On the Run: Fugitive Life in an American City (Chicago; London: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Bernard E. Harcourt, Against Prediction: Profiling, Punishing and Policing in an Actuarial Age (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), Language of the Gun: Youth, Crime, and Public Policy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), and Illusion of Order: The False Promise of Broken Windows Policing (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); and Loïc Wacquant, Punishing the Poor: The Neoliberal Government of Social Insecurity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009).

↑ - 12

See Isabelle Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010).

↑ - 13

Marc Dessauce, The Inflatable Moment: Pneumatics and Protest in ‘68 (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1999).

↑ - 14

Achille Mbembe has argued that this forms a new kind of “necropolitics,” a variety of biopolitics that emphasizes the control of death, not only life. See Achille Mbembe, “Necropolitics,” Public Culture 15, no. 1 (2003): 11-40.

↑ - 15

See Dell Upton, Architecture in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998); John Michael Vlach, Back of the Big House: The Architecture of Plantation Slavery (Raleigh-Durham: University of North Carolina Press, 1993); Michael Henry Adams, Harlem: Lost and Found (New York: Monacelli Press, 2001); Ellen Weiss, Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee: An African American Architect Designs for Booker T. Washington (Montgomery: NewSouth Books, 2012); Craig Evan Barton, ed., Sites of Memory: Perspectives on Architecture and Race (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001); Dell Upton, “Commemorating the Civil Rights Movement,” Design Book Review 40 (Fall 1999): 22-33; and Wilson, Negro Building.

↑ - 16

Fields, Architecture in Black.

↑ - 17

See also Lesley Naa Norle Lokko, ed., White Papers, Black Marks: Architecture, Race, Culture (London: Athlone Press, 2000); and Irene Cheng, “Race and Architectural Geometry: Thomas Jefferson’s Octagons,” forthcoming in J19: The Journal of 19th-Century Americanists.

↑ - 18

See David P. Brown, Noise Orders; Héctor Tarrido-Picart, “Phonotropolis: Designing a Sound City,” Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy (2014): 20–28; Sekou Cooke, “The Fifth Pillar: A Case for Hip-Hop Architecture, Harvard Journal of African American Public Policy (2014): 15–18; and the upcoming symposium Towards a Hip-Hop Architecture.

↑ - 19

See Garry Stevens, “Struggle in the Studio: A Bourdivian Look at Architectural Pedagogy,” Journal of Architectural Education 49, no. 2 (November 1995): 105–122; and Felicia Davis, Yolande Daniels and Mabel Wilson, “Inside and Out: Three Black Women’s Perspectives on Architectural Education in the Ivory Tower,” in Space Unveiled: Invisible Cultures in the Design Studio, ed. Carla Bell (London; New York: Routledge Press, 2014).

↑ - 20

Monica J. Casper, “Black Lives Matter / Black Life Matters: A Conversation with Patrisse Cullors and Darnell L. Moore,” Truthout, December 3, 2014.

↑