Black Spaces Matter

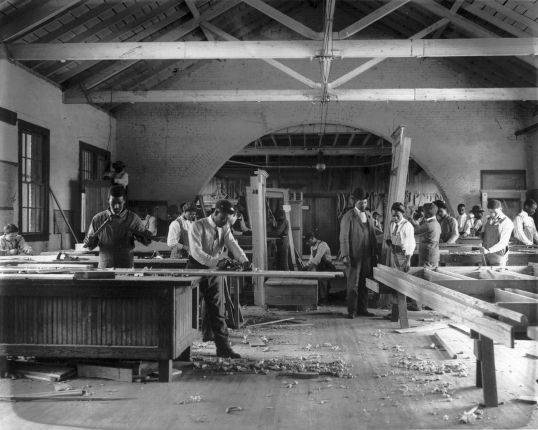

If we agree with recent protestors that black lives matter, then we must also insist that black spaces matter, for race and place have been indelibly linked in American history. It was a fascination with building character that led Booker T. Washington and Robert Robinson Taylor to shape Tuskegee Institute into a living model of black social uplift.1 Their approach trained both the “heads” and “hands” of their charges: While Taylor and his students built up the physical grounds of the school, Washington gave weekly addresses on how to achieve middle-class respectability.

Students constructing a wood roof truss at Tuskegee Institute.

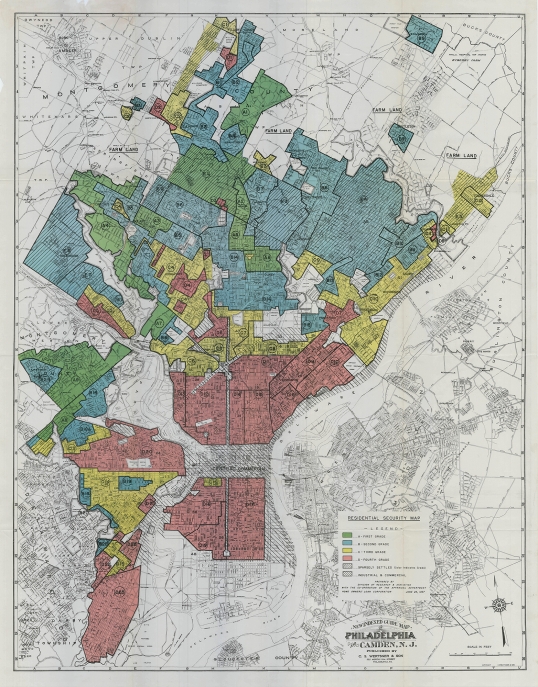

Redlining Map of Philadelphia, Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (c. 1937).

It is precisely because of the rhetorical power that black spaces hold over the public imagination that the current reassessment of black life has so much potential. The black female activist Alicia Garza challenges us to reimagine the social horizons of black life with her simple claim that “Black Lives Matter.”2 Prompted by her disappointment with George Zimmerman’s acquittal for the murder of Trayvon Martin in July of 2013, Garza sought a powerful way to reaffirm the value of black life. She established a Facebook page and later a Twitter feed to motivate herself and others to challenge anti-black racism around the country. Her sentiments, however, require her to do battle with a range of historical imagery that reifies the notion that black life is cheap, that poor black life is almost meaningless, and that black masculinity is the most important form of black life in society. This challenge not only forces us to recognize the multiple subjectivities of black bodies, but also to situate these subjectivities within a material reality that safely maintains their livelihood. It means considering all of the black bodies (plural) that are affected by anti-black racism, and it means considering black space as a conceptual site of social protest—as the architectural corollary of the meme Black Lives Matter.

Architects and architectural historians will find an exemplary model of this type of ethos in the writings of June Jordan. As a female artist, she demonstrates the value of black feminist leadership in enabling black lives. Yet, she understood the media’s fixation with black masculinity and spoke to black boys in an effort to prepare them to cope with the unwarranted attention of the police state. Probably more crucial for architects and architectural historians, however, is her presiding interest in black space as a productive site of intervention. Her work instructs readers to ponder the latent potential of abandoned or neglected spaces, and it is this optimism and ingenuity that can be influential in this moment of renewed social protest.

JUNE JORDAN AS MODEL

June Jordan employed poetic language to enliven her thick descriptions of everyday black spaces. The characters in her poems and novellas use “black English” in their verbal exchanges, a source of color that was controversial for an author attempting to contribute to literature in the most traditional sense. She also paid attention to the physical contexts of her characters without unnecessarily belaboring their textures, sights, and sounds. Her attentiveness to the daily patterns of poor people’s lives is not entirely surprising given her activist concerns. However, it has only recently come to light in architectural history that she consciously employed modern architectural principles in her writings as well. In this way, her literary oeuvre served as a parallel of the architect’s sketchbook, constantly verbalizing a set of experimental principles that complement the typical media of the professional architect (e.g., through drawing, modeling, or physical construction). Despite having no physical structures credited to her name, June Jordan—a female artist and a woman of color, a college dropout with no architectural license—was consistently drawn to and incorporated the principles of modern architecture throughout her career. And she did so in the service of ennobling the value of black lives.

Jordan’s architectural interests began with her acceptance into the Environmental Design program at Barnard College.3 After dropping out of Barnard, she began a serious reading program of architectural journals and history surveys in the art reading room of the Donnell Library in New York. In her memoir Civil Wars, she fondly recalls her “fantastic visual inundation” in Greek architecture when courting a series of biographical writings published in the 1980s:

At the Donnell I lost myself among rooms and doorways and Japanese gardens and Bauhaus chairs and spoons. The picture of a spoon, of an elegant, spare utensil as common in its purpose as a spoon, and as lovely and singular in its form as sculpture, utterly transformed my ideas about the possibilities of design in relation to human existence.4

During this formative time, she developed the roots of what one historian has called her “ecosocial” interpretation of the built environment, which considered architecture and the built environment to be an extension and manifestation of human ecology.5 This preference for the social led her to elevate Buckminster Fuller’s ecological utopianism over Le Corbusier’s technocratic solutions for distinctly zoned postwar cities. (The fact that Fuller had also dropped out of school made him an approachable figure in Jordan’s eyes.) Fuller’s solutions for domed cities seemed to layer all of the mess and clutter of the urban condition in its organic and emergent condition. This textual love for Fuller blossomed into a real correspondence with the architect and subsequent collaboration on the “Skyrise for Harlem” project—an alternative urban design solution to the “New York” approach to urban renewal.6 Jordan was later awarded a Rome Fellowship Prize in Environmental Design, where she conducted research on communal agrarian reform. This work synthesized the themes of race and place by bringing together the communal ideals of Fannie Lou Hamer (the black feminist activist) and the utopian ideals of Fuller’s architectural speculations. However, the greatest testament to Jordan’s architectural expertise is likely to be found in the manner in which she employed architectural description and metaphor in her written work.

HIS OWN WHERE

An explicit example of the architectural and urban design principles implicit in Jordan’s work can be found in her 1971 novella, His Own Where.7 Jordan’s book describes the experiences of Buddy, a young black boy who is forced to live on his own after his father is hospitalized by an errant car. Buddy’s life teaches him that black space can be aggressive and unforgiving toward black life, and therefore is not always to be trusted. In addition to the vulnerabilities that street corners and other vagaries of the urban grid present to poor black residents, he learns that the massive restructuring of urban infrastructure, educational policy, and other forms of institutional neglect indirectly affects one’s future. The only comfort that Buddy finds in life is in the art of carpentry, which his father taught him before being hospitalized. In the years following his divorce, Buddy’s father radically reconstructs the interior space of their 1960s brownstone along modernist principles and passes along this responsibility to Buddy in his absence. Although Jordan never uses the term “architect” or “architectural” to describe Buddy, his father, or the spatial transformation of their brownstone, her description of the spare and minimalist aesthetic of the interior recalls her early exposure to modernist architecture in the Donnell Library.

The newly stripped walls of Buddy’s formerly bourgeois interior are a manifestation of what I like to call the alternative modernisms established by Jordan’s text. This sort of modernism is adaptive; it thrives on found spaces and seeks opportunities to influence the city from the bottom up. While not officially sanctioned by any disciplinary body in architecture, it represents the strategic spatial appropriations that are required for marginalized subjects to participate in modernism’s social projects. In contrast to the efforts of Le Corbusier and the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM) to position the professional architect as the privileged regulator of physical spaces, Jordan places the tools of modern architecture within the hands of a fifteen year-old boy. He has no teacher besides his father and his own mind, and yet these are enough for him to gain control over his own space. In fact, he is doing more for black lives and spaces than the official bodies set up by the state to do so. Buddy’s informal education causes him to constantly think about the city in spatial and architectural terms. His leisurely rides through the city become mental exercises in imagining a timeshare arrangement for the skyscrapers and business towers that lay dormant in the city center after hours, or to think of ways to elevate interior space as a physical element to be shaped and celebrated instead of filled with possessions and clutter. Jordan’s textual depiction of Buddy’s design ethos gives him a glint of the handicraft roots of Adolf Loos or Mies van der Rohe, although far more tempered by the neglect and want of the 1960s. It is a radical black version of architectural culture that pluralizes the restrictive canons that reinforce the social exclusions of the postwar period. In a biographical sense, Jordan’s attempts to synthesize race and place in her works constituted an effort to come to grips with the race riots and abject poverty that marked Harlem in the mid-to-late 1960s. She wanted to move beyond the hate she felt for her oppressors by providing the urban residents of these segregated enclaves with a glimpse of hope, even if this hope was largely textual in form.

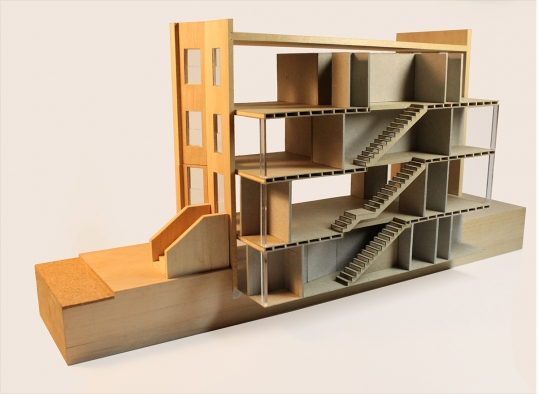

The immediate architectural implications of Buddy’s world can be manifest if one imagines the modified interior spaces of his historical brownstone.

Model of Buddy’s brownstone before the transformation.

Model and photo by Adam Caruthers.

Model of the physical transformation of Buddy’s brownstone.

Model and photo by Adam Caruthers.

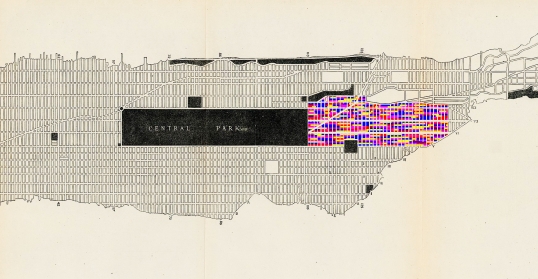

“Architextural” map of Harlem revitalized by the urban design principles of His Own Where.

Drawing by author.

Collage illustrating the implications and roots of Jordan’s “Architextural” principles: (a) digital model of Buddy’s house, (b) “Architextural” map of Harlem, (c) frontispiece of June Jordan’s His Own Where (1971), and (d) “Skyrise for Harlem” collaboration by June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller (1969).

Drawing by author.

PROJECTIONS

I tend to agree with the black feminist Pauline Gumbs that “June Jordan was an architect” in the most expansive sense, that is to say in the sense that counts most for the progression of architecture as a discipline.8 Despite her lack of legal and professional credentials, Jordan’s language is aligned with the techniques, strategies, and suppositions of progressive postwar architects. In light of this situation, it is fruitful to consider her literary output a synthetic hybridization of her poetic and architectural talents. This reading builds upon Cheryl J. Fish’s “architextural” characterization of Jordan’s career; the architectural implications of her genius remain pregnant in her poetry and prose.9 Her textual utopianism seems no less real or influential for not being translated in the traditional media of the architect. The textual form of her output was shaped by her need to reach the aspiring young black readers who wanted to dream, but did not think of architecture as an obvious career choice or mode of experimentation. Jordan served as an intermediary for the many who had limited physical agency to reform their environment, but were discovering a new sense of self-worth as a result of the radical messages communicated by various black social movements. Architects and architectural historians would do well to emulate her work today.

✓ Not peer-reviewed

Charles L. Davis II, “Black Spaces Matter,” Aggregate 3 (March 2015), https://doi.org/10.53965/XZOU4701.

- 1

Robert Robinson Taylor was the first African American to graduate from MIT’s Architecture program. See Ellen Weiss, Robert R. Taylor and Tuskegee: An African American Architect Designs for Booker T. Washington (Montgomery, AL: New South Books, 2012).

↑ - 2

Alicia Garza, “A Herstory of the #BlackLivesMatter Movement,” BlackLivesMatter.com, December 6, 2014, accessed January 11, 2015, http://blacklivesmatter.com/a-herstory-of-the-blacklivesmatter-movement/.

↑ - 3

Environmental Design was an umbrella curriculum introduced in the 1950s and 1960s to teach designers of all kinds the importance of shaping the built environment. Many of these programs were not accredited because they exceeded the boundaries of professional education.

↑ - 4

June Jordan, “One Way of Starting This Book,” in Civil Wars (Boston: Beacon Press, 1981), xvi–xvii.

↑ - 5

Cheryl J. Fish, “Place, Emotion, and Environmental Justice in Harlem: June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller’s 1965 ‘Architextural’ Collaboration,” Discourse 29, no. 2 (2007): 332.

↑ - 6

June Jordan and Buckminster Fuller, “Instant Urban Renewal,” Esquire, April, 1965.

↑ - 7

June Jordan, His Own Where, reprint ed. (New York: Feminist Press at CUNY, 2010).

↑ - 8

See Alexis Pauline Gumbs’s essay, “June Jordan and a Black Feminist Poetics of Architecture,” Plurale Tantum, March 21, 2012, http://pluraletantum.com/2012/03/21/June-Jordan-and-a-Black-Feminist-Poetics-of-Architecture-site-1/.

↑ - 9

Cheryl J. Fish, “Place, Emotion, and Environmental Justice in Harlem,” 332.

↑