Signifying Media: The Imprinting of Palladio

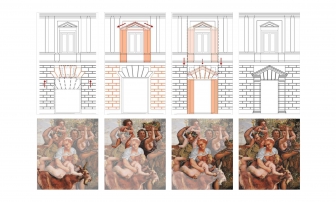

Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Figural elements repositioned.

Digital visualization by the author.Fig. 1. (a) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, Vicenza, 1565–1580. Photograph by the author.

(b) Andrea Palladio, Loggia del Capitaniato, Vicenza, 1565–1572. Photograph by the author.

Portraying Barbaro’s Signifying Process

It is a common understanding that Palladio’s imprint on architecture—the canonical impression he has had on its history—is due in large part to him being the first architect in print, that is, the first architect to publish images of his own built work and projective building projects, which appeared in his 1570 publication I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura. This self-illustration of actualized designs (and those Palladio hoped to actualize) is in contrast to the hypothetical building designs in Sebastiano Serlio’s volumes that were published within his lifetime, or the designs in the fifteenth-century codices of Filarete and Francesco di Giorgio Martini that, like the rest of Serlio’s volumes, only made it into print centuries later. But the radical imprint of printing—and other media with which Palladio was directly associated—on his own architecture is a subject requiring a closer reading. This is in no small measure because it would not be possible to comprehend the later buildings that have perplexed many observers, in particular Palazzo Valmarana (1565–1580, Fig. 1a) but the Loggia del Capitaniato (1565–1572, Fig. 1b) as well, without—to use another of the definitions of imprint—taking into consideration the “impression produced by pressure, printing, or stamping” on a surface, indeed the very pressure of printing and other media, which in turn will result in the stamp of Palladio’s imprint on centuries of direct and indirect Palladianism. And further, without understanding the impressive (in the literal sense) combinatory multiscaled layering in the façades of these buildings, it would not be possible to understand the late work of Palladio’s churches (Figs. 2a, b), in particular the manifestation of a multiple imprinting onto the surface of their façades—the unsettling interpenetration of dual façades that Rudolf Wittkower called attention to in his “Principles of Palladio’s Architecture,” the first of his essays that would be developed into the Palladian section of his Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism.1

Fig. 2. (a) Andrea Palladio, San Giorgio Maggiore, Venice, 1565-1576. Photograph by the author.

(b) Andrea Palladio, Church of the Redentore, 1576-1586. Photograph by the author.

It was Daniele Barbaro, Palladio’s patron both of book and of building, who stated—in his commentary in the edition of Vitruvius for which he commissioned illustrations from Palladio—the value and significance of providing graphic impressions in order to make a cultural impression. Even more significantly, Barbaro posited the epistemological imperative that you can only know something through the distinction of its impression, in both the literal and figurative sense. In his discussion of Vitruvius’s statement that “all fields, and especially architecture, comprise two aspects: that which is signified and that which signifies it [quod significatur et quod significat],”2 made right in the first chapter of the first Book, Barbaro explained that the signified is the proposed work and the signifier is manifest reason (dimostrativa ragione)—expressed, in James Ackerman’s translation, in the following manner: “To signify is to demonstrate by signs [significare è per segni dimostrare], and signing is to impress [imprimere] the sign. When the work has been controlled by reason and finished with drawing [disegno], the Artificer [Artefice] has impressed [impresso] his sign, that is, the quality and the form that was in his mind” (Fig. 3).3

Fig. 3. Danielle Barbaro, I Dieci Libri dell’ Architettvra di M. Vitrvvio (1567), 11. Library, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

The more recent translation of this passage by Kim Williams includes the original declarative opening (absent in Ackerman’s translation), while translating imprimere and impresso as “imprinting” and “imprinted”: “But by way of declaration I say that signifying is to demonstrate by signs, and signing is imprinting the sign. Hence, every work erected according to rationale and finished by design is imprinted with the sign of the maker—that is, the quality and the form that was in his mind.”4 This signifying impression/imprinting—I will be utilizing both relational meanings here—constitutes not a static condition but rather a dynamic process, as Ackerman has observed:

That process is described as “discourse”—Discorso—which is Barbaro’s rendering of Vitruvius’s ratiocinatio… . Discorso is the equivalent of disegno, a term much more widely used at the time, which is most effectively defined by Barbaro’s contemporary Vasari as denoting not only the process of drawing but the conception of any work of art. Barbaro’s “discourse” suggests an action and, still more, an ongoing interaction, a process.5

With regard to these relations, Margaret Muther D’Evelyn has noted that in “Italian, as in English, ‘segno’ or ‘sign’ is at the root of the word ‘disegno’ or ‘design.’”6 This co-incidence of discourse and the media of its re-presentation, design and sign, will result in many of Palladio’s later works manifesting as enactments of demonstrative signification, as “an action and, still more, an ongoing interaction, a process.” In these buildings, this active and interactive process demonstrates, through its dynamic signing, the manifest imprint of drawn reasoning.

It was this desire “to communicate [desiderato … di communicare],” expressed by Barbaro right in his commentary of Book I, that instigated his employ of “M. Andrea Palladio Vicentino Architetto” to provide “drawings of the important figures [disegni de la figure importanti].”7 These drawings, it may be observed, include the tectonic figures of the orders and their associated elements, as well as the sculptural figures of reliefs and statues. Indeed, as Barbaro stated later in his commentary on Book III, in order for reasoning to be communicatively manifest, it needs to be expressed as a distinctively recognizable figuration: “Human cognition [humani cognitione] . . . whether of the sense or of the intellect, commences first with confused and indistinct [indistinte] things, but then drawing nearer to its object, becomes more definite and certain.” Thus, Barbaro initially chides Vitruvius for providing “us with an indistinct and confusing cognition of temples, taken from their figure and appearance, since the figure is a common object among sensible things,” but he notes further that the latter “descends then to the distance between parts, and will finally arrive at the particular and definite measure of every participle.”8 In terms of these figurations, if Barbaro’s conjoining of signifier and signified into signs brings to mind the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s similar articulation of these terms four centuries later in his proposal that the sign is the combination of the concept-signified and the image-signifier, these two individuals distant in time and forms of scholarship nonetheless coincide as well in regard to distinctive cognitive expression: “any conceptual difference perceived by the mind seeks to find expression through a distinct signifier, and two ideas that are no longer distinct in the mind tend to merge into the same signifier.”9

In Barbaro’s stated investigation of truth (investigare la verità), it is Palladio’s “most subtle and graceful drawings of plans, elevations, and sections [sottilissimi, & vaghi disegni della piante, de gli alzati, & de i profili]” that are being called upon, as precisely measured, to provide particular and definite figurations, transforming general, indistinct figures into distinctively figured signs. But Barbaro’s second adjective, vaghi, might give us pause here. While this translation is certainly correct in selecting this meaning from the others of the Italian root vago in this time, the word’s primary signified sense—vaga, errante—coming from the Latin root vagus, conveys those other meanings: doubtful, roaming, uncertain, unfixed, unsettled, unsteady, vague, and wandering.10 What becomes evident in considering the signifying effects of Barbaro’s and Palladio’s media campaigns is how, paradoxically, the distinct delineations of Palladio’s orthographic graphic technique—in the merged dimensional collapse of its projection and printing—resulted in the ambiguous dimensional distinctions of Palazzo Valmarana, the churches, and other later works through the collapsed figural merging of their recursive multilayers. The result is a subtle and sometimes not so subtle mobile unsettledness—“an action and, still more, an ongoing interaction, a process”—which indeed reveals the evidence and effects of agency in their media. This transmedial unsettledness will be related further in the sections below to the dimensional ambiguities and self-reflexivity of another medium in these campaigns: the trompe l’oeil frescoes within Palladio’s buildings, notably including those frescoes Paolo Veronese painted at the villa in Maser that Palladio had designed for Barbaro and his brother Marc’Antonio.

In Veronese’s well-known portrait of this patron in the Rijksmuseum, Daniele Barbaro is shown demonstrating the discursive quality of his reasoning by displaying pages depicting distinctive delineations he had in his mind of emblematic signs of architectural and astronomical figurations, imprinted as in his 1556 Vitruvius, along with a backdrop of their “actualized” related counterparts—interactively multilayered, as will be addressed in later sections, through the recursive foreground, middle ground, and background of the painting (Fig. 4a). Unlike the more generalized earlier portraits of Barbaro, the Rijksmuseum portrait has been aptly utilized by numerous commentators as the one that most signifies the official cultural and social portrayal of Barbaro’s character. Starting in the middle ground with his status in the ruling elite of Venice, Deborah Howard observes that his “ecclesiastic’s cape or mozzetta and finely pleated white muslin surplice,” a form of dress, is “readily associated with patriarchs.”11 This status is directly connected in the portrait’s fore- and midground to Barbaro’s extensive engagement with scholarly writing.12 The painting depicts his edition of Vitruvius as the media work he is most identified with and the work, as portrayed in this portrait, which most enacts and identifies him in the midst of imprinting his signifying practice through media. As Xavier F. Salomon has recognized, Barbaro’s grip on the book directs us not to its title, nor surprisingly to the very authorial name of the person being portrayed, let alone to the author being translated—all of which would have appeared toward the top of that page had Veronese not compositionally and tellingly defined this portrait’s edge by their extended absence—but rather to the bottom line of text (Fig. 4b), which even with its painterly drafted inscription signifies the publisher’s imprint (to use a third sense of this term).13

Fig. 4. (a) Paolo Veronese, Portrait of Daniele Barbaro, 1565-1570. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

(b) Paolo Veronese, Portrait of Daniele Barbaro, detail, 1565-1570. Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

(c) Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Portrait of Giulio Romano. Web Gallery of Art.

Duncan Bull has observed how Veronese’s positioning of Barbaro and his media coincided with that of another significant portrait by this fellow Venetian painter, as it makes “use of the device, employed by Titian in his portrait of Giulio Romano of ca. 1537 [Fig. 4c], of showing a sitter holding an item that indicates his intellectual achievements while turning away from it.”14 Barbaro’s turning thus turns us toward the book itself, whose portrait this painting is of, as much as it is of Barbaro—even honored and titled with the only legible word (LIBRO) in the otherwise pseudo script of the painting. In this regard these painted pages have come to signify how Barbaro’s two decades spent waiting to become Patriarch of Aquileia—perpetually the next in line from his election in 1550 to his death in 1570—allowed him the time to pursue such intellectual achievements. In contemporaneous written accounts this seemingly contemplative patrician is portrayed nonetheless as a defender of a civically active life, as Manfredo Tafuri has noted, with a “strong need for action guided by theory,” and thus like Vitruvius critiquing the spatial practices of his contemporary Roman times, Barbaro felt compelled in his Vitruvius to comment on contemporary Venetian spatial politics. These comments ranged in scale from his critique of the local domestic building traditions of his fellow patricians, to his advocacy to modernize the construction of the civic institution of the Arsenale, to more extensive territorial recommendations regarding the reform of the fortifications of the city and the ecological management of the Venetian lagoon.15

What is significant is that in this strong need for action Barbaro felt the further need, in his commentary and edition of Vitruvius’s I dieci libri dell’architettura, to enlist the graphic attentions of Palladio, considering that this was the first book the architect would illustrate. Two years after Barbaro and Palladio’s trip to Rome, I dieci libri dell’architettura (1556) appeared under the imprint of the Venetian publisher Francesco Marcolini, “one of the two most prominent printing shops in Venice during the mid-sixteenth century.”16 This particular venture of Barbaro would initiate for Palladio a whole series of encounters with the then still relatively new medium of the illustrated printed book, fostered by the reigning Venetian book industry, which one estimate proposed published more than sixty percent of all the printed editions in Italy during this time period.17 Palladio’s engagement with publishing would lead to his I Quattro Libri fourteen years later, published under the imprint of Domenico de’ Franceschi, and five years hence, to his illustrated Italian edition of Julius Caesar’s Commentaries. This latter volume was printed by Domenico’s brother, Pietro de’ Franceschi, but the rights were held not by a publisher but by Palladio himself (a fifteen-year privilegio to protect his prints from being copied by other engravers), the co-incidence of illustrator and printer engaging in a joint venture of imprinting. But Palladio’s encounter with the Venetian book industry would lead to more than just a series of personal publications. This transmedial locus of exchange fostered innovative modes of mediated disegno, new acts of exploring representation as a mode of design and design as a mode of representation.18 Indeed, a series of historical investigations in the 1970s by Decio Gioseffi, Howard Burns, and Marcello Fagiolo in the Bollettino del Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio attempted to account for the unsettling dimensional ambiguities through this media effect on the late designs of Palladio, particularly with regard to his Palazzo Valmarana (Fig. 5). To account, in the words of Gioseffi, for:

how and where such practice of graphic design and development of the project has conditioned the objective outcomes of his architectural activity. Where, that is, in the completed work or in the final project, the presence of a given solution (or non-solution) can be attributed to the “pressure” of the conventions inherent to the chosen graphic notation system, more than to any “semiological institution” accredited within its specific field by the current building practice.19

Fig. 5. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, Vicenza, half-elevation, woodcut, I Quattro Libri dell’Architettura (Venice, 1570), Book II: 17.

What is particularly significant is Gioseffi’s and Fagiolo’s own analytical use of visual representations in those articles—how the graphic orientations of these authors conditioned the objective outcomes of their own philological activity. The significance of that would be easy to overlook, as regarding this particular palazzo there is only a single visualization in Gioseffi’s article and two in Fagiolo’s, with merely three associated sentences in each text describing the analysis of the visualization amid many rather more generalized observations.20 Nonetheless, those accounts begin to explicate how Palladio’s media techniques put into play and into question certain cultural techniques of signification. If, as Gioseffi proposed above, a given resolution by Palladio can be attributed to the “conventions inherent of the chosen graphic notation system, more than any ‘semiological institution,’” the resultant late works nevertheless pressured the very epistemological and semiological institutionalization of architectural language and practice in this time—through their dynamic elision of the act of signifying (through the demonstration of signs) with the act of signing (through the impress of signs) onto the surfaces both of Palladio’s books and of his buildings.

Palladio Inside-Out

The reason why the multilayered and multireasoned Palazzo Valmarana was the shared locus of these investigations is because this building is the most problematic of all his villas and palaces, due to it being the most complexly mediated, indeed transmediated, of all his works. Wittkower’s characterization of the building in his Architectural Principles in the Age of Humanism—a critical work that influenced all postwar Palladian discussions—stated that “the system of Palazzo Valmarana is not coherent,” that “in no other building did he attempt an equally deliberate break with established classical conventions.”21 Four hundred years after the fact of I quattro libri and one year after Wittkower’s death, Decio Gioseffi, in “Il disegno come fase progettuale dell’attività palladiana,” seeking some sense of coherence in the design of this building through a reading of its mediated imprinting modes, noted that Palladio’s favored form of representation—orthogonal projection—enabled a dimensional ambiguity of visual equivalence and interchangeability between full columns, half columns, and pilasters, as they may be perceived to slide back and forth along the axis of projection.22 Gioseffi stated that he set up a side-by-side photo montage comparison (Ho fatto pone a riscontro in un fotomontagio) of Palladio’s preparatory I Quattro Libri drawings for Palazzo Porto’s courtyard and Palazzo Valmarana’s façade (Fig. 6a) in order to provide an example of what he called the “the modality of transfer [modalità del trapasso].”23 Gioseffi proposed that the array of detached two-story Composite columns from the inner courtyard of the earlier Palazzo Porto may be seen to emerge on the later Palazzo Valmarana not as full columns but as Composite pilasters—in the manner of the effect intrinsic to transparent or translucent layers of tracing paper, wherein an image on an inner layer emerges into the visual field of an outer layer. Gioseffi described this mode as “a process of progressive exploration within the orthogonal method, the ‘discovery’ of the basic indifference to the situation or position of the object (as well as of the projection plane) with respect to each sliding in the ‘forward-backward’ sense along the axis of projection,” which “finally proposes the theoretical interchangeability between ‘elevations’ and ‘sections.’ That also implies some consequences on the design level: and could eventually suggest a rather unconventional use of transfer using ‘tracing paper.’”24

If it seems anachronistic for Gioseffi to refer to mediated modes of transparent tracing, it should be noted that Palladio is already utilizing representations of “ghostly” traces in his initial drawings of Palazzo Porto in the mid-1540s, with traces of interior elements (the central tetrastyle atrium of Tuscan columns) appearing on the façade in one drawing (RIBA XVII/12, both on the recto and the verso) (Figs. 6b, c), as well as outside elements on another façade study (RIBA XVII/9), indicated as roundels drawn in faint outline above the ground-level windows.25 Such varying traces of transparency provide the transition from an inside impressed on an outside surface, as well as an outer layer impressed on an outside surface.

Fig. 6. (a) Dario Gioseffi, Comparative representation of Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto section and Palazzo Valmarana elevation. Dario Gioseffi, “Il disegno come fase progettuale dell’attività palladiana,” Bollettino del Centro Internazionale di Studi di Architettura Andrea Palladio 14 (1972), n. 33.

(b, c) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto, RIBA31790 XVII/12 recto and verso. Douglas Lewis, The Drawings of Andrea Palladio (Washington, DC: International Exhibitions Foundation, 1981), 113.

These early representational experiments become more fully manifest in Palladio’s illustrations in the 1556 and 1567 editions of Barbaro’s Vitruvius, in which particular columns of outer temple colonnades and palace porticos are depicted as transparent or translucent, allowing the façades beyond to become demonstratively visible. As Guido Beltramini has noted, within the context of “a radical change in architectural publishing at the time”—from earlier publications in which “perspective or pseudo-perspective representation is more or less predominant” to “the 1556 edition of Vitruvius and, with some slight yielding in the additional images, also of the new edition of 1567: almost all the ancient buildings and their details are represented by orthogonal projections with innovative techniques, such as transparent elements in the foreground making it possible to see through to the background elements.”26 Making it possible, in other words, to see that the architect has seen through and apprehended the building as a multilayering of related foregrounds and backgrounds, manifesting and signifying this epistemological reasoning in and through the medium of disegno. It was the epistemological play enabled by various forms of signifying media that Palladio engaged in or encountered in his time that manifested as equivocal modes of representation in his own signified artifacts—his drawings, books, and buildings—in ways that still may unsettle certain received histories today.

With regard to Gioseffi’s hypothesis about the relationship between Palazzo Porto and Palazzo Valmarana, this mode of transfer of background to foreground could be called (although Gioseffi does not do so) a technique of inside-out, the pressure of an inside emerging toward an outside—literally an inside colonnade emerging to the outside façade, figuratively from inside the personal and typological history of Palladio’s design dispositions and their repositioned evolution. Barbaro, in his commentary on the signifier and the signified, stated that the Artificer first “operates in his intellect and conceives in his mind.”27 and only subsequently signs the exterior material with this interior disposition (habito, or abito in the contemporary spelling, which may be rendered alternatively as “attire,” “habit,” or “inclination”).28 Gioseffi takes his cue regarding his transfer not from Barbaro’s description of the inside-out inclination in this distributive dis-position of the intellect but from the action of the eighteenth-century collector John Talman, who pasted together two separate preparatory I Quattro Libri drawings Palladio of the outside elevation and the inside section of Palazzo Porto—drawings first acquired around one hundred years earlier by Inigo Jones during the architect’s Grand Tour (Fig. 7a). The clue to this mode of comparative inside-out, for both Talman and Gioseffi, comes from Palladio himself, from the drawing, also acquired by Jones, of Palazzo Valmarana with this same split-screen layout of the elevation on the left side and the courtyard view on the right (Fig. 7b). It is this latter drawing upon which Jones had the audacity to sketch what would appear to be some of the figural attributes of the building on the verso side (Fig. 7c)—two statues (only the smaller of which has any semblance to the figures evident in the constructed building or its representations.29) and of a Corinthian capital (with three enlarged versions of acanthus detailing)—in a darker iron gall ink than Palladio’s, as if to leave his own imprint on (and off of) the back of Palladio. Which in fact bled right through the front in one area of the drawing and left traces of the rest of Jones’s sketching obscuring the visibility of Palladio’s drawing.

Fig. 7. (a) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto, Talman composite, RIBA31779 XVII/3. Douglas Lewis, The Drawings of Andrea Palladio , 117.

(b, c) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, RIBA31780 and 31781 XVII/4 recto and verso.

This trace “showing through” (to use the bibliographic term) of Jones’s gall—in both the figurative and the literal sense: his impudence and his ink—has no shared coordinates with Palladio’s drawing on the reverse side, unlike a number of other instances of “showing through” to be examined here. The possibility of creative innovation through the perception and actualization of coordinates that coincide between delineated surfaces has been available to architects since the translucence of the medium of parchment or paper was able to register the impressions of the designer as impressions on a surface—through the coincidental effect of being able to show through the impressions from one side to the other or from one sheet to another. When there are no shared coordinates between these impressions, then the resultant effect is coincidental in the nonsignificant use of the term—merely happenchance. But if the designer notes the co-incidence of shared co-ordination and makes use of them to create an assembly greater than the sum of their individual parts, then the significant sense of coincidence as only apparently happenchance—the sharing of incidence that reveals or results in a surprising relation—is enacted in the design. The impress, in other words, of seemingly different attributes or conditions imprinted each upon the other.

In fact, these courtyard columns of Palazzo Porto exist only as such in print and as print, given that the original palace had been designed in 1546 (twenty years earlier than Palazzo Valmarana) and its construction completed by 1554, with little likelihood of this version of the courtyard being built. This did not stop Palladio from projecting, literally and figuratively, this fabrication of a giant order in the courtyard in the (forever) future tense: “The courtyard … will have columns thirty-six and a half feet high, that is, as high as the ground floor and second story together.”30 Like architects in every century since, Palladio hoped that by getting the prospective project in print the client would be impressed—in the sense of feeling admiration and respect, as well as fixing the idea in their mind—to the extent that the client would be imprinted (in the behavioral sense of the word) to follow the architect into construction.

Fig. 8. Andrea Palladio, Venezia: Palazzo Porto 1546-1552 and Palazzo Valmarana 1565-1580. Rudolf Wittkower, “Sviluppo stilistico dell’architecttura palladiana,” figs. 53, 54.

Thus, whether the courtyard section for Palazzo Porto was designed before or after the design for Palazzo Valmarana, this now reverse engineering by Palladio provides a series of clues and missing links to help us comprehend the transformation from his earlier Palazzo Porto (Fig. 8, left)—which followed a Roman mode of palazzo design with its clearly demarcated rusticated base and ennobled second level—to the evolution decades later with the self-reflective play of these demarcations in Palazzo Valmarana (Fig. 8, right).

This latter palazzo is even more “ennobled,” with its giant order reaching from the piano rustico up into the piano nobile, but also thus more localized, as unlike in Rome the nobles of Vicenza occupied both the ground level as well as the second level. But unlike the other late palazzo designs of Palladio that feature giant orders (the initial scheme for Palazzo Barbarano, the unbuilt Palazzo Angaran, the fragment of Palazzo Porto Breganze)—each resolved in a repetitive symmetrical manner—Palazzo Valmarana is co-incidental in a syncopated manner: the major-order Composite pilasters are impressed upon the medium-order Corinthian pilasters that extend laterally past the major order, presenting a structural switch that shockingly gives the appearance of leaving the ends of the building only precariously supported (Fig. 9). Shocking certainly, as Ackerman noted, to Francesco Milizia, who two centuries later, in 1781, wrote, “Everyone can see that this combination of colossal and small pilasters that spring from the same level, and the intersection of the cornice by the colossal pilasters, are not in a pure taste. The worst is that at the corners there are only Corinthian pilasters up to the first story, and on the second only a soldier with his back to the wall.”31 Milizia is channeling here Tommaso Temanza’s criticism of this corner from the two decades earlier Vita di Andrea Palladio (1762):

Here Palladio believed it sufficient to substitute a Corinthian pilaster of the minor order, on the cornice of which he placed a statue of a Soldier, with his back to the wall, which fills the void up to the architrave of the Composite order… . Nevertheless, our Andrea is not exempt from censure, due to the excessive weakness that the work shows on the corners; in which architects have always endeavored to show greater solidity than in any other part of the building.32

Fig. 9. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana: “The excessive weakness that the work shows on the corners.” Photograph by the author.

“A Soldier, with his back to the wall”—what Milizia and Temanza are signifying here is that this statue does not appear to be remotely as intent in his capacity to work as a load bearer as, say, the caryatids with capitals that Palladio illustrated in Book I of Barbaro’s Vitruvius or the similarly structural atlantes with bent heads illustrated in Book IX. Temanza’s censure is cited by Wittkower—“the disquieting effect of this arrangement was observed and put on record in the 18th century when Temanza lamented that the comers had been weakened though these were just the points which should show the greatest strength”—as a way to underwrite his own anxiety. Which Wittkower then tried to mitigate by stating—and here can be cited his extended statement without yet adjudicating its veracity: “But this was precisely what Palladio intended to do. In no other building did he attempt an equally deliberate break with established classical conventions.” And yet again, these defensive statements are followed immediately in the next sentence by a restatement of his unease regarding the deliberation of Palladio’s breaks with established conventions: “Language and patience have their limits when describing a Mannerist structure, and many other features of this building may be left unrecorded.”33

Ironically, Wittkower used more language and patience in his direct description of this building than he did of any other villa or palace of Palladio. And some features Wittkower did record, although mentioned by neither Temanza nor Milizia, are further examples of its “extremely complicated interplay of wall and order”:

For the small Corinthian order is not applied to a proper wall. The ground to which it is attached, is rusticated, but the rustication has been given a particular meaning. The strips at the sides of the windows have been treated to look like Tuscan pilasters with their own capitals, and this results in the impression of a third order. Above the windows are reliefs, and as they are in a deeper plane than the rustication, the latter appears like a frame to them, the lower border being at the same time the lintel of the windows.34

What is particularly notable here is the way in which this building instigates Wittkower’s own complicated interplay of precise description and dubitable equivocation. The multilayered trompe l’oeil effects of the building produce apparitional appearances, manifest dynamically rather than statically through shifting processes of signifying—tectonic figurations that have been “given a particular meaning” other than expected, which have been “treated to look like” something they are not, which “results in the impression” of something other than what they would seem conventionally to be, which “appears like a frame” while “being at the same time” a lintel.

Fig. 10. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana “rustication.” Photograph by Marianna Mancini.

In terms of dimensional and semiological impressions, it should be observed that this background is imprinted with Palazzo Porto–style rustication inscribed in relief. Since Bramante’s invention for Palazzo Caprini of faux rustication (bricks covered in stucco), this simulacrum of a signifier had become widespread during the Cinquecento.35 But at Palazzo Valmarana this simulation is evident only as just the barest of impressions (Fig. 10), just lines incised into the elevational surface. These incisions might seem figuratively like the lines incised into the woodcut block Palladio utilized to print its representation in I Quattro Libri, but that would only be the case literally and figurally had he incised those corresponding lines directly into a metal engraving plate, rather than inversely into a wood block. What is the case is that these lines in the building do not even attempt to give the appearance of structural blocks extending into the third dimension, as is the case at Palazzo Porto. What is especially disquieting is that in their exposed depth, the ground-level window apertures—which at Palazzo Porto are delineated through the continuation of the joint lines from the front façade—remain blank at Palazzo Valmarana. Indeed, in the latter, all the elevational “blocks” stop short of the edge of these openings, making even more evident their atectonic and astructural depiction as surface. Also stopping short as well, in the building’s current manifestation, is the “book-ended” rustication on the implied pedestals (visible, for example, in Fig. 8, right, and Fig. 20)—present in the eighteenth-century elevation published by Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi in his Le fabbriche e i desegni di Andrea Palladio (vol. 1, 1776), although not in any of Palladio’s elevations. Even though made to appear to wrap around their corner conditions, nonetheless these rougher-textured “blocks” do not reach across the pedestal’s empty center, resulting at the inset corners in a disconcerting half-version, barely “supportive” of the smaller order as not even the width of the full Corinthian shaft—all the more thus manifest as a graphic representational trace of structure.

The significance of these seemingly unreasonable structural abuses—to use Palladio’s own term (abusi)—is the most compelling and telling aspect of the imprinting of Palazzo Valmarana, in that they have compelled critics throughout the centuries to puzzle over them and what they might signify as the surprising or unsettling demonstrations of Palladio’s “reasonings.” In other words, they remain of interest for what they might reveal about his work and workings—“the quality and the form that was in his mind”—given that Palladio has often been portrayed through the centuries as perhaps the most reasonable of all architects. In chapter XX in the first book of I Quattro Libri, in the section entitled “On Abuses,” Palladio railed—uncharacteristically, given his entirely measured and reasonable tone throughout—against the fabrication of any building element that diminishes its primary purpose, which according to him is “to appear to produce the effect [paiono far l’effeto] for which they were put there, which is to make the structure … look secure and stable.”36 Palladio’s own equivocal choice of wording—“to appear to produce the effect” and “to make the structure look secure and stable”—is telling in the same way as Wittkower’s, as in the Cinquecento the demonstration of the signs of structural re-presentation appears more important than demonstrating the actual reality of structure. Yet the imprinted layers in Palazzo Valmarana belie the look of security and stability in the aforementioned abuses and in two further significant seeming mis-formations. Located in the same bay as the end statue, directly above the pedimented window, is an opening that cuts through the frieze and architrave of the top entablature, weakening it just where it should be particularly reinforced as it approaches its end point (Fig. 11a). The general principle regarding weakened corners had been stated by Daniele Barbaro in his Vitruvius: “And if I can put them [the windows] at a distance from the corners, will it not be better than putting them at the corners and weakening the house?”37 And Palladio echoed this principle later in his I Quattro Libri: “But the windows and the openings must be kept as far from the corners as possible … because that part of the building which must keep all the rest aligned and held together must not be open and weak.”38 At Palazzo Valmarana, this puncture in a primary horizontal structure might easily have been assumed to be an unconscionable alteration to the building in a later century by an insensitive subsequent owner with no respect for the well-known architect’s signifying intent, were it not illustrated exactly in this manner both in the elevation in I Quattro Libri and in the drawing that Jones sketched upon. Notwithstanding the implied structural break in this implied structure, this opening and the end bay windows in the ground and second levels might still be said to just pass Palladio’s proposed rule (as a way of maintaining the security and stability of a building) that “at least a space should be left between the opening and the corner that is as wide as that opening.”39 This would be so were it not the case that in the uppermost attic level the space between the corner and the end window is much less than its width by quite a considerable degree, less than three-quarters, as is similarly illustrated in both the printed elevation and the drawing.

Fig. 11. (a) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, corner entablature window. Photograph by the author.

Another especially considerable structural abuse is the “weakening” of the mid-entablature by the giant order (Fig. 11b). The latter is not just positioned in front of or even flattened against the former—which even so would have revealed and made manifest the fiction of its structural appearance—but rather is cutting right into and through it to the degree that the two topmost moldings of this entablature’s cornice (the outward curving gola diritta capped by the flat ordo) actually stick out past the pilaster. An apparent structural co-incidence producing the visual effect of making what should appear as a continuous whole horizontal structure (even one set back, held up by the second order) look unsecure and unstable is as shocking an abuse, it would seem, as terminating the building’s edge with a statue. And while Wittkower proclaimed, as cited, that in no other building did Palladio “attempt an equally deliberate break with established conventions,”40 it should be noted that in the Cinquecento the incentive for a willful and creative breaking of established conventions as a means to develop new figurations in the articulation of knowledge was articulated in The Book of the Courtier in the assertive statement Baldesar Castiglione gave Count Ludovico da Canossa to voice: “Do you not know that figures of speech, which give so much grace and luster to discourse, are all abuses [abusioni] of grammatical rules[?]”41

Fig. 11. (b) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, cut entablature. Photograph by the author.

Gioseffi, for his part, noted only the matter of the giant order and its absence at the building’s extremes, without noting, however, how this absence amounts to an extreme abuse of classical grammar, at least to Temanza, Milizia, and Wittkower. Quite to the contrary, as evidenced in the published lecture notes from his course on Palladio (1972–1973) at the Università degli Studi di Trieste, delivered during the time of the article in question, Gioseffi posited that Palazzo Valmarana is “in reality neither inconsistent nor disorganized; but it duly derives from the ‘orthogonal codification’ of a very real system developed in depth… . the alleged elements of ‘rupture’ are all implicit in the mechanism … of the transposition.”42 An argument he makes precisely in order to explain away any disquieting implications of the design attentions or intentions of Palladio that so unsettled Wittkower.

While Gioseffi’s insightful apprehension of the shared visual attributes between these seemingly disparately composed buildings, and consequently his technique of representing them at the same scaled format as Palladio prepared them for print, made their relations particularly evident, questions remain regarding how duly is the derivation from one to the other, in the transmedial transaction of its transposition. By “apprehension,” I am referring, in part, to the epistemological ability to perceive and comprehend the figurations of an aesthetic object. But equally, it is evident that the ambiguities enacted in the development and manifestation of these late objects of Palladio have caused that other sense of apprehension, precisely for epistemological reasons: an unease due to certain insecurities and instabilities regarding the ability to perceive and comprehend the figurations of these objects in the “pure taste” of received convention by critics such as Milizia, Wittkower, and indeed Gioseffi. In order to evade any claim of “rupture,” Gioseffi’s phrase “duly derived” (puntualmente deriva) asserts that this graphic transposition may be apprehended as wholly consistent and organized in the moment of its derivation, invariably and precisely complete without any compositional, semiological, or (particularly worrisome for Gioseffi) ideological remainder. This evasion elicits a third meaning of apprehension: to attempt to arrest, through the critic’s authority, any alleged worrisome artistic activity, the historiographic context of which I will return to in the concluding section.

Nonetheless, Gioseffi’s preliminary comparison of Palazzo Porto and Palazzo Valmarana can initiate the means to further account for the mediated development of these structural mis-formations in particular and the evolution from Palladio’s earlier to later work in general, providing some of the evidence necessary to proceed to track further the later complex transformations of Palladio’s work by utilizing some newer forms of digital media. It is important first to note what Gioseffi, in his side-by-side visualization, did not do, which is what is implied in what he said Palladio did do, that is, to slide forward Palazzo Porto’s courtyard façade along its own axis of projection (Figs. 12a, b), which would mean sliding it into and onto its own front façade, “plaiting” (his verb) them together (Figs. 12c, d)—which I have animated in Figure 12e. In addition to the giant Composite columns, a number of other elements in the Porto courtyard section not mentioned by Gioseffi are present in both buildings, namely the secondary-order Corinthian pilaster that Palladio says would “support the floor of the loggia above,”43 the second-story unpedimented windows with “ears” toward their bases, and the two cut-out apertures at the mezzanine levels of both stories. One does not have to “construct” ex nihilo the graphic scene of this co-incidence, this inside-out emergence from behind the façade four centuries after the fact of its imprinted manifestation, as it is already evident and manifest in each and every original and facsimile edition of I Quattro Libri (even if unnoted by Gioseffi), wherein Book II one can see the multilayered trace showing through Palazzo Porto’s section as the verso (page 10) of its recto façade (page 9) due to the translucent material-quality of paper used in book print production in any and every century.

Fig. 12. (a) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana, shifting along “the axis of projection.” Digital visualization by the author.

Fig. 12. (b) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana, shifting along “the axis of projection.” Digital visualization by the author.

Fig. 12. (c) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana, shifting along “the axis of projection.” Digital visualization by the author.

Fig. 12. (d) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana, shifting along “the axis of projection.” Digital visualization by the author.

Fig. 12 (e) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana, shifting along “the axis of projection.” Animation by the author.

Had Gioseffi actually brought Palazzo Porto’s inside to its outside, he could have recognized that other disquieting attributes of Palazzo Valmarana that he did note in passing could similarly be accounted for through the very modality of transfer he had just proposed four paragraphs prior. Such as the already mentioned slicing through of the mid-entablature that he called, with deliberate hyperbole, the order’s “cry of pain” (Fig. 13a). There is also the capitals’ “protest” in relation to “the ‘contestation’ of the upper doors” (Fig. 13b)—a figuration described by Wittkower wherein “the window frames in the piano nobile touch the entablature above, and are hemmed in at the sides by the enormous capitals,” with the result that an “unequal, typically Mannerist, competition arises between the slender moldings of the window frames and the bulky mass of the pilasters.”44 Not noted by Gioseffi but visible in this conjoined façade are other disquieting effects (Fig. 13c), such as the aforementioned imprinting between the pilasters of a trace of Palazzo Porto rustication in relief.

Fig. 13. (a) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto Courtyard Elevation and Façade Elevation Overlaid, the capitals’ “protest” in relation to “the ‘contestation’ of the upper doors.” Digital highlighting by the author.

(b) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto Courtyard Elevation and Façade Elevation Overlaid, the Orders’ “cry of pain.” Digital highlighting by the author.

(c) Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto Courtyard Elevation and Façade Elevation Overlaid, “rustication.” Digital highlighting by the author.

What Gioseffi did observe is the difference in the base datums of the two giant orders, and thus he understandably lifted up the columns that rest on the ground in the Palazzo Porto courtyard to match their elevated position on pedestals in the Palazzo Valmarana façade. But rather than reposition and rescale just the columns, he rescaled the entire Palazzo Porto plate, throwing off the co-incidence of the other comparable coordinates. In order to comprehend this comparable process of transformation from the earlier to the later palazzo as a series of coordinated design actions, it is most productive to proceed sequentially and consequentially in order to verify the hypothesis of the relation between these two palazzos in their positioning and repositioning. In other words, if we take Gioseffi’s suggestion of their mediated relation but proceed beyond his initial two steps (bringing the columns forward and then elevating them), by following through to further correspondences we can track a number of simple transformative steps that it would take to complete the substantive transformation that these modes of transfer made possible through these imprinted means (Figs. 14a–g). Using the I Quattro Libri woodcuts for more precise comparability, the following is one of several possible sequential and consequential serial transformations that may assist us in comprehending the designed relations between the two palazzos as initiated by Gioseffi, with no claim as to whether this sequence was the definitive order of steps Palladio undertook:

Fig. 14. (a) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana (extrapolating Dario Gioseffi’s hypothesis): Overlaid elements. Digital visualization by the author.

(1) Following Gioseffi, the giant courtyard order is brought out to the façade but in addition, and by association, so too is its continuous top entablature and visually discontinuous mid-entablature, all of which are flattened into the surface of the façade (Fig. 14a). The result is that, as mentioned, the pilasters appear to cut what should properly be a continuous mid-entablature. And, as mentioned, the other elements emanating from the Porto courtyard relevant to Palazzo Valmarana are brought forward as well: the smaller Corinthian order, the mezzanine openings from the first and second levels, and the large unpedimented windows from the second level that replace Porto’s front façade pedimented windows. This latter repositioning results in the condition at Palazzo Valmarana observed by Wittkower regarding the “hemming in” of the window frames at the top and sides. The exception is the end window, which remains pedimented but consequently is compressed and scaled down to fit under the entablature.

Fig. 14. (b) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Figural elements repositioned. Digital visualization by the author.

(2) Before proceeding to elevate the giant order, one should note two consequences of this action with respect to the second-level entablature being brought forth from the Palazzo Porto courtyard, both of which are repositions of figural elements (Fig. 14b). First, the mid-entablature of the courtyard, when brought forward, crowds and consequently compresses the end pedimented window in the piano nobile, and the reclining figure that had been positioned above that window in Palazzo Porto’s façade is consequently repositioned transversely to Palazzo Valmarana’s central portal. Second, the lack of the giant Composite column in the end bay could have left that bay supported in the piano nobile by Palazzo Porto’s Ionic single-story column, but the transition to Palazzo Valmarana may be obtained by the former’s end roof statue being repositioned vertically downward to become the end sculptural support, rescaled so that its pedestal matches the height of the pedestals of the adjacent window framing.

Fig. 14. (c) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Giant order repositioned. Digital visualization by the author.

(3) The giant Composite order can now be elevated along with the secondary Corinthian loggia support from the courtyard (Fig. 14c).

Fig. 14. (d) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Secondary order redistributed. Digital visualization by the author.

(4) This secondary order is redistributed laterally to the ground-level apertures as flanking pairs and as one full pilaster to complete the missing corner position, which provides the appearance of supporting the end statue (Fig. 14d).

Fig. 14. (e) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Rustication redefined. Digital visualization by the author.

(5) Also at the ground level, Palazzo Porto’s courtyard mezzanine windows (which are rectangular along their sides and bottom edge) are redistributed along Palazzo Valmarana’s ground level as a single window at the end bay and figural panels in the other bays (Fig. 14e). Another aperture shift occurs at the upper level, as Palazzo Porto’s courtyard single upper mezzanine aperture—which in its very representation in I Quattro Libri indeed cuts through the frieze and architrave of the entablature with which it coincides—is repositioned laterally to Palazzo Valmarana’s end bay. The result is that other disturbing structural “abuse”—the weakening of the façade entablature in the very place Barbaro and Palladio said to avoid (Fig. 14f).

Fig. 14. (f) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Mezzanine window penetrating entablature repositioned. Digital visualization by the author.

(6) This completes the comparative sequence (Fig. 14g), which is animated in Figure 14h.

Fig. 14. (g) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana: Completed sequence. Digital visualization by the author.

Fig. 14. (h) Transformational sequence of Palazzo Porto to Palazzo Valmarana. Animation by the author.

Regarding the ground-level windows of the palazzo, we can also return to the previously mentioned earliest incidence in Palladio’s drawings of an inside-out transparency, the verso of the alternative façade study for Palazzo Porto (RIBA XVII/12). It depicts the delineated imprint of the four freestanding Tuscan columns of its entrance tetrastyle atrium emerging from inside-out into the surface of this earlier façade, establishing a co-incidence with its outer “rusticated” blocks and voussoir. The double impression of the column and the first ground-level window to the right of the arched entrance coincides in a nearly exact match to the framing, position, proportions, and primary figurations of Palazzo Valmarana’s middle ground-level apertures (Fig. 15): the Tuscan capitals, the stacking of six cut-off rusticated blocks flanking the window, and the delineation of Palazzo Porto’s inner atrium entablature slicing horizontally through this earlier version’s five voussoirs coinciding with Palazzo Valmarana’s flattened arch, five-voussoir, pittabande-like figuration. All that would be required to complete the basic configuration is the slight lateral shift of the capitals atop the vertical stacking and the subsequent edge-squaring of the outer two “stones.”

Fig. 15. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Porto and Palazzo Valmarana window overlap. Digital visualization by the author.

It should be noted that the elaboration of this transformative process initiated by Gioseffi involved not only the single whole tectonic element he brought from the inside of one palazzo to the outside of another but also elements whose impress only emerged as identities in the graphic act of being cut through in section, such as Palazzo Porto’s courtyard loggia beam end that emerges as the projective portion of Palazzo Valmarana’s lower entablature as a “support” for the end soldier. Howard Burns, in an early version of his essay “I designi,” published a year after Gioseffi’s text, noted this formative sectional phenomenon in the “massive and a bit strange detail” of the “big blocks that protrude from the frieze of the courtyard of Palazzo Valmarana” (Fig. 16), which “can have its origins in those Palladian sections where the large beams of a salon are cut, giving the impression of something protruding from [sporge dal] the frieze.”45

Fig. 16. Andrea Palladio, Palazzo Valmarana, courtyard, protruding frieze “beams.” Photograph by the author.

What really may be stated as truly more than a bit strange is the “unreal” applied and implied fictive impression in low relief of beam ends in the more conventional form of triglyphs in classical architecture, which is why Burns may be unsettled enough here to note this protruding beam detail. Two related attributes may be proposed that contribute to Burns’ sense of strangeness here, both of which are conveyed in his use of the phrase “protrude from”: First, while it may be stated that portions of the frieze above the columns stick out, jut out, thrust forward, it is also the case that relational portions of the cornice do as well. This figuration might normally be understood as a conventional projective entablature had the associated architrave and column projected forward as well, rather than remaining flush with the backgrounded area of the frieze. Second, thus while this separation provides the strange sense of a thrusting forward from the frieze, the incompletion of this usually co-ordinated convention results in a disjunctive displacement between the upper and lower positioning of this standard tectonic figuration.

Thus, Gioseffi’s initial inside-out dis-placements and re-positionings provides a perspective to perceive these further displacements, replacements, and repositionings. Sliding not just backward and forward, as he suggested, but also laterally and transversely along the surface of the façade, actively instigating such operations through these representational techniques of media. Representations not just leading to, but manifesting as constructed reality. Not things represented as they “should be” constructed in reality, “complete and robust” as Palladio states toward the end of his “On Abuses,”46 but rather things constructed as they are represented—like the trompe l’oeil frescoes that suffuse the interiors of so many of Palladio’s buildings, which I will discuss in the concluding section. What is revealed in this equivocal ambiguity of things that are constructed “to appear to produce the effect … to make the structure … look secure and stable” are certain epistemological insecurities and instabilities inherent in the mediated production of appearances, impressed as they are through the Artificer’s signifying act, in the transition Barbaro proposed from inside the mind to outside sign.

Palladio Outside-In

While Gioseffi described for the conception of Palazzo Valmarana a mode of inside-out, literally and figuratively, Howard Burns in “I designi”—published first, as mentioned, the following year in the 1973 exhibition catalog Mostra del Palladio and expanded later that year in the Bollettino del CISA—proposed a mode that could be called (although he also does not) outside-in.47 This may be considered literally as an outside portico or colonnade pressed onto the façade in the form of pilasters or attached columns, and figuratively as outside of Palladio’s own designs through his research into the works of antiquity:

And I would propose that solutions like those of the façade of San Giorgio and of Palazzo Valmarana have been suggested to the author by his own drawings from antiquity or from his own inventions. But these must now be interpreted not as representations (which in fact they are) of a deep spatial composition with columns in the round, but as a kind of low relief in which the columns become pilasters, or are “crushed” against the wall, as in the facades of the churches.48

The imprinting that Palladio’s own internal design dispositions and repositioned development received through his study of antiquity has been well documented, as has the way his hypothetical and imaginative reconstruction of those constructions became a way for him to put his own imprint on architecture. But Burns, in two subsequent single-paragraph catalog entries for the 1975 exhibition Andrea Palladio 1508–1580: The Portico and the Farmyard—“Elevation of the façade of the Temple at Assisi” and “A plan of the Forum of Nerva and an elevation of the Temple of Minerva”—extended in two significant ways his argument that Palladio’s orthographic reconstruction studies of antiquity “employed the drawing as a two-dimensional scheme, which could be translated back into three dimensions in a whole variety of ways.”49 The first observation, that “Palladio used his drawings of ancient buildings as models, rather than the buildings as they actually stood,” has been noted by Beltramini, who summarizes this insight as follows: “When he comes to use this antique motif for his own projects—the pilasters of the Palazzo Valmarana or the half-columns of the Palazzo de Porto in Piazza Castello—the source is not so much the real Temple of Minerva as his drawing on this sheet.”50 Not the building, but Palladio’s impression—figuratively and quite literally and figurally—of the building, re-figuring these antique edifices into and onto the surfaces of paper and project, the surfaces of books and of buildings.

Burns’s second insight involved a similarly radical misreading of the drawing, wherein what Palladio clearly shows as the considerable depth and height difference of the portico of the temple relative to the surrounding enclosure of the temple complex, the columns of which, as Palladio stated, “lack pedestals but rise from the ground,” are flattened in elevation into a composite surface.51 This dimensional difference is re-presented by Palladio in the spatial contraction that is the graphic technique of every elevational drawing—which in turn, as proposed by Burns, is “how Palladio could justify and arrive at as unclassical a scheme for a church façade as that of S. Giorgio Maggiore … with half columns, and its side portions articulated with columns which rested on the ground.”52 In Book IV of I Quattro Libro, Palladio represents spatially contracted combinations of raised central columns and lower side columns in the form of elevational and sectional reconstructions not only for the Temple of Nerva Trajan but also for the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, in both cases with examples of the smaller columns presented as interspersed with the larger ones. Similar combinatorial layering of differently scaled orders was re-produced not only on the surface of San Giorgio Maggiore but also on Palladio’s earlier San Francesco della Vigna and his later Il Redentore. In Palazzo Valmarana, the rare pedestaled full columns in Assisi—of which Palladio says: “in every other ancient temple one sees columns of the porticos resting on the ground and I have not seen any other which had pedestals”—reappear in I Quattro Libro, as Burns noted, transformed as pedestaled giant-order pilasters.53 This seeking to adopt and be adopted into a desired ancestry, to be imprinted by established conventions as well as by the connoisseurial obscure, unconventional, and thus exceptional examples of antiquity, were re-produced by Palladio in his late work as new adaptations, mutations, and recursive recombinations. Burns, more recently, has stated that this representational mis-reading was one of Palladio’s most potent design strategies: “Orthogonal drawing for Palladio is an instrument of transformation, a means of generating several designs for a single ancient elevation or from one of his own designs… . he willfully and creatively reads his own elevation drawings in different ways, transforming an ancient temple front into a palace elevation with pilasters, or an open elevation with free standing columns, like the Palazzo Chiericati, into a closed façade with half-columns, like Palazzo Barbarano.”54 Thus, the instrumental techniques of orthogonal drawing no longer remain merely illustrative of a design but through their dimensionally ambiguous engagement become generative, in a transmedial manner, through which Palladio developed recursively self-referential transformations of prior works—his own and those of antiquity.

For Burns, Palladio’s drawings, “if they are observed in an ‘active’ way, suggest various spatial possibilities.:”55

the wonderful creations of Palladio of the last fifteen years (and not only of those) often have their effectiveness in a daring and very original (and at the same time practical and economic) tradition of schemes with round columns into schemes that adopt pilasters and half-columns. Thus the facade of a temple, thanks to the mediation of a drawing, can become the facade of S. Giorgio Maggiore. And the design for the courtyard of Palazzo Da Porto Festa can become—as Gioseffi brilliantly and graphically demonstrates—the façade of Palazzo Valmarana.56

As Burns proposed, it is not necessary to adjudicate whether the positioning of the giant order at Palazzo Valmarana should be perceived as a foreground layer of columns repositioned outside-in toward a background layer, as he posited, or a background layer of columns repositioned inside-out to a foreground, as Gioseffi posited. And further, it should be noted that in addition to Palladio’s drawing and printing, the spatial possibilities enacted in an active way through the conjoining and interlocking of foregrounds and backgrounds is at work in a number of other media in relation to which Palladio was directly engaged, as will be discussed in the concluding section. For now, with regard to the media of drawing and printing, the hypotheses of Gioseffi and Burns should be understood as co-operative, co-citational, and co-incidental in terms of their design modes of apprehension and development.

Regarding the several senses of apprehension previously cited, before describing why a simple, albeit willful and creative, back-and-forth along an axis of orthogonal projection, whether inside-out or outside-in, is a necessary but not totally sufficient explanatory principle to account for the complexity of Palazzo Valmarana—through the range of creative misreading Palladio employed through orthogonal projection as he prepared for print—it is important to address first why there was this shift to orthogonal projection in the Cinquecento. Particularly given the received sense of the Renaissance pictorial development as being focused on perspective as a key representational mode. When an acclaimed expert at perspective like Raphael writes in 1520 to urge Pope Leo X to commission a survey of works of Roman antiquity, insisting that “since the way of drawing specific to the architect is different from that for the painter, I shall say what I think opportune so that all the measurements can be understood and all the members of the buildings can be determined without error,” it is because, as he says, “an architect cannot get correct measurements from a foreshortened line.”57 The Renaissance desire to imitate the ancients, to maintain the imprint of antiquity—its “characteristic marks and indications,” to cite another of the definitions of “imprint”—is for Raphael a desire to maintain the ancestral imprinting of Roman antiquity against the invasive medieval contamination of the “Goths and other barbarians,” as he and his coauthor Castiglione state in the letter. This is a form of imprinting in the behavioral sense of establishing patterns of recognition and association to be able to follow one’s own kind. In order for this linkage to be “established firmly” (another definition of “imprint”), you need a truthful and accurate documentary representation of its characteristic marks and indications, which orthogonal projection was seen to provide. And for Raphael this desire was not only for a distant ancestral linkage but also for a more immediate filial imprinting in order to establish his relation with the most important architect of recent time, evidenced, as he writes, in those “modern buildings … very clever and very closely based on the style of the ancients, as can be seen in the many beautiful works by Bramante.”58 Fifty years later Palladio will seek the same filial association by producing orthographic illustrations of Bramante’s Tempietto as the only modern building (other than his own) included in I Quattro Libri. What is particularly astonishing in Raphael’s letter to the pope is that the “truth” of visual experience that perspective was able to achieve at this point in history becomes considered, by one of its most adept practitioners, as a form of inaccurate “falsehood.”

And yet, the dimensional flattening of orthogonal drawing that aimed to demonstrate things as they are lacked the ability to demonstrate things as they are perceived (and thus conceived) spatially and temporally, and thus it is not surprising that innovative forms of representation were utilized in Barbaro’s 1556 edition of Vitruvius, which attempted to enact the simultaneous layering of spaces and surfaces (outside-to-outside, outside-to-inside, and inside-to-inside) through various modes of visualization: the transparencies already mentioned, elevations and sections side by side as split-screen comparisons, cut-away three-dimensional views, even several illustrations that were reproduced as separate, smaller layers of paper that could be rotated or lifted up off of their pages, as in the exterior view of a bastion at the end of chapter VI of Book I that is layered in the form of a flap over its interior view (Fig. 17).

Fig. 17. Daniele Barbaro, I dieci libri dell’Architettura di M. Vitruvio tradutti e commentati da monsignor Barbaro eletto patriarca d’Aquileggia, (Venice, 1556). Avery Architecture & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University. Photographs by the author.

On the verso of that particularly dynamic page, in a passage that Barbaro acknowledges “has wandered far” from his specific commentary on Vitruvius’s text, Palladio and his contribution are referenced for the first time in the book (the bracketed text below indicates 1567 additions to the original 1556 text):

More than once I have desired [and sought] to communicate my efforts to others so that [before they came to light] we could together investigate the truth, but this, for some reason that I don’t quite understand, has not happened. In the drawings of the important figures I have used the works of Mr. Andrea Palladio, architect of Vicenza, who has to his incredible advantage, from what I have seen with my own eyes and that which I have heard in the judgement of excellent men, acquired a great name owing to both the most subtle and graceful drawings of plans, elevations, and sections, as in what will follow, and in the execution and making of many superb edifices in both his own region and in others, [both public and private,] that contend with the ancients, illuminate the moderns, and will fill those who come after with marvel.59

Missing in this recent translation of Barbaro’s slightly revised 1567 text is a significant sentence (present in both the 1556 and 1567 editions) that comes directly after the phrase “investigate the truth.,” which would not only help explicate Barbaro’s puzzled and somewhat puzzling lament that follows but which would also underscore the significance of Barbaro’s seeking out Palladio in his desire to have the architect’s mode of communication incorporated in this printed endeavor. That sentence—“accioche quello, che non puo fare uno solo, fatto fusse da molti” (So that, what cannot be done by one would be done by many)—expressed not only Barbaro’s desire for many colleagues to share in the initiative and labor of this enterprise but also his desire for a shift in the collective consciousness of history and homeland.60

In the latter regard, the imprinted mass marketing recently available in this time and in this region fostered the publication of multiple revised versions of Barbaro’s Vitruvius in 1567—under the imprint of the Venetian publisher Francesco de’ Franceschi Senese & Giovanni Chrieger Alemano Compagni—as it seems what cannot be done by one version of this book marketed to one class of reader would be done by many versions marketed, as noted by Robert Tavernor, to many classes of readers:

two in Italian—a large folio edition of 1556 (at 42.5 x 29 cm it was the largest publication of its time) and a more practical quarto edition of 1567, which has a revised text and smaller illustrations—and one in Latin, a folio edition of 1567 which was originally intended as a companion edition to the 1556 Italian folio. They were aimed at different readerships: the smaller Italian edition of 1567 was less expensive than the earlier folio edition and targeted practising and would-be architects, while the Latin edition was published for a more scholarly and international readership of potential patrons of buildings.61

In the smaller, less expensive version, Barbaro’s lofty address to Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, to whom the work is dedicated, is followed immediately by an even lengthier marketing pitch “To the Readers” by the publisher, Francesco de’ Franceschi Senese. The latter announced that, through this more accessibly convenient commodity, he “wished, good readers, for the common good, to bring to light both versions of Vitruvius [“the Latin” and “the vulgar”], and to use all diligence to produce them in a form that is convenient [forma commoda] … accommodated to this new form so that everyone can enjoy the fruit of the erudite efforts of my aforenamed lordship.”62

For his own personal enjoyment, the erudite efforts of this aforementioned lordship included the production of his villa by Palladio, occurring around the same time as the production of his Vitruvius with Palladio. Villa Barbaro was one of the first of a series of villas to reproduce in its façade the giant order that the architect had imagined for his drawing Reconstruction of the façade of the Roman House printed in the book. In terms of projective perceptions, Palladio’s imaginary reconstruction of the Roman House was based on the self-image of his own intended designs rather than on any description by Vitruvius. A decade later, bringing this outer portico into town and onto the surface of the Palazzo Valmarana (not as in Villa Barbaro, in attached-columnar form, but flattened further into pilasters), Palladio for the first time was able to deploy a giant order on a private palazzo, so that “those most distinguished gentlemen, the Counts Valmarana,” could make a grand impression for, in the words of Palladio, “their own glory and the convenience and ornament of their homeland”—considering as Giovanni Alvise Valmarana had managed Palladio’s first public project, and was a crucial supporter of Palladio in the competition for the Basilica after years of debates “between traditionally hostile, rival lobbies.”63 As for the glory, convenience, and ornament of the homeland, while for the final city council decision regarding the Basilica there was substantial (but not unanimous) support for Palladio among the Vicentine patricians, yet, as documented by Tafuri, the adoption of a nonlocal Roman language in the Veneto hardly seemed “convenient” for all the Venetian patricians—in the sense meant in the quotation above from I Quattro Libri: as accommodating and as suitable to represent ornamentally what would signify as the appropriate identity of the local patria, the homeland. In the local battles between the reforming Romanists and the traditionalists, Palladio’s architecture remained, as Tafuri observed, “a ‘novelty’ [novità] that Venice could assimilate only with difficulty.”64 For Barbaro personally, the assimilative identity of homeland involved a multilayered imprinting, given that, as Louis Cellauro noted, the “Barbaro family claimed ancient Roman ancestry and roots in the Venetian mainland which predated the formal development of the Republic itself.”65 In this sense these political acts in the impressing of refined signs in the Veneto may be compared to Niccolò Machiavelli’s use of the same word used by Barbaro—imprimere—in the former’s Discourse on Livy regarding how Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, impressed new forms on an unrefined people: “those men with whom he had to work were unlearned [grossi], this gave him great ease to carry out his designs [desegni], because he was easily able to imprint [imprimere] on them any new forms [nuova forme] whatsoever.”66 All the more reason in this period for Barbaro and Palladio to attempt to impress their reasoning—their demonstrations of the signification of their signs—by seeking to imprint with a renewed significance these signs of a Roman ancestry onto those unlearned in these matters by being locally imprinted in more recent generations and centuries.

What cannot be done by one, would be done by many: in this period, which Tafuri has described as “characterized by the convergence of many efforts intent on modernizing the State” wherein “a technical and scientific renovatio was one of the means of this process” through which “a scientism was affirming itself,”67 what may be noted here are the dimensional multiplication and interplay of the impressed technical and scientific signs between the foreground and background in Veronese’s Barbaro portrait. Manifest behind the book horizontally held by the Barbaro, the one displaying its own imprinting, is another copy, vertically propped up to display an analemma, the orthographic projection of the sun’s motion, which Barbaro devised to illustrate not only Vitruvius’s description of it in Book IX, but more significantly the Patriarch’s own astronomical research. One example of Barbaro’s attempts to control reasoning and finish by drawing through his invention of astronomical instruments, which included the design of the flattened sundials prominently impressed upon the exterior dovecote ends of the villa that Palladio designed in Maser for him and his brother Marc’Antonio—and upon whose interior wall surfaces Veronese impressed his own dimensional interplays in the trompe l’oeil frescoes. As for the dimensional interplay of this portrait’s analemma, it is doubled on its own page, coincident with the surface of the painted page as a flat diagram above while below it emerges dimensionally to be depicted in depth as a plane curling into the curved figure of a sundial. Conjoined with that figuration is the figure of a putto standing outside the diagram, simultaneously behind and shifting forward to over-see its viewing from above. The putto is holding the edge of the dial with its left hand while pointing with its right hand to the analemma delineations, using a linear instrument meant to signify the gnomon that would cast its instructive shadow on the actual dial.68 In other words: the putto is pointedly demonstrating the act of signifying.

As stated by Barbaro in his commentary on this page, this is a presentation of the conjoined figuration of artistic and scientific signification: “the Figure [of the analemma] is below, with another Figure, which we have made for ornament and beauty, demonstrating how it can vary, by preserving the rule, & the form of the Horologists.”69 Thus: ornament and beauty conjoined with—in order to be the signifying conduit of—the rule and the form as so designated by those sorts of overseeing specialists that Barbaro and his patrician associates were proposing to designate. In Veronese’s multilayered portrait of this recursive space of a projective imaginary, the media of these signifying signs of science and architecture are further multiplied as the foregrounded, two-dimensional, micro-scaled diagrams in the books are scaled up as backgrounded, representative, three-dimensional “actualizations”: the armillary sphere modeling these solar motions right behind the upright analemma page, and behind that, on a high pedestal, a modified version of the columns Palladio had depicted on the imprint page.