Iconoclasm beyond Negation: Globalization and Image Production in Mosul

Fig. 3. Still from an ISIS video showing the apparent destruction of ancient artifacts at Mosul Museum, February, 2015.

Available at Times.While iconoclasm is arguably as old as representation itself, its internal dynamics are historically specific. The destruction of artifacts and/or images that occurs under this designation is not only sanctioned by a shifting set of belief systems and cultural conditions, but so too is it circumscribed by specific modes of representation and technologies.1 Approaching recent events in Mosul with this recognition in mind serves to connect these performances to larger questions regarding the media environment in which these acts took place. It also opens the prospect of reverse engineering these displays so that they might divulge the complex network of forces, both cultural and technological, that undergird their operation. This project requires reevaluating two primary assumptions that structure our everyday understanding of iconoclasm: first, that iconoclasm functions as an originary act that takes place independently of the media by which it is made available to its audience; and second, that iconoclasm is solely an operation of negation or erasure. Reconsidering these assumptions not only excavates the power relations behind contemporary acts of iconoclasm, it also serves to acknowledge a dynamic symmetry between the destruction of artifacts by extremist groups such as ISIS and similar actions by the U.S. military in the region.

The shifting relations between iconoclasm and representation are perhaps most visible in the redefinition the monument has undergone at the hands of modern media. In the course of the Reformation, the French Revolution, the Soviet cult of personality, and the dissolution of the Eastern Bloc, the cultural position of the monument has become inextricably bound to its destruction. In recent years, this relationship between statue breaking and history has escalated to the extent that the unveiling of the monument, and indeed the presence that it obtains thereafter, rarely if ever so fully enters public consciousness as its destruction does. The monument in the context of the post-9/11 “war of images” exemplifies this new status as its capacity to serve as target is recast as its primary role. W. J. T. Mitchell even goes so far as to claim that, in addition to the lure of oil and the unfinished business of President George W. Bush’s father, it was the prominence of monuments and other large-scale historical markers in Iraq compared to Afghanistan that made it a more attractive destination in this war of representation.2

In this context, the commemorative function of the monument, let alone its sheer visibility, proves capable of working through a reversal of presence whereby disappearance no longer proves synonymous with forgetting or loss, but rather forms the condition of possibility for a specific mode of image production. In light of this reversal, it no longer suffices to speak of monuments as casualties of war or revolution. As Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin describe, once the monument’s “potential for destruction or defacement” begins to function as “the most meaningful aspect of the monument’s existence as an object,” then its destruction becomes its realization, its primary means of signifying.3 The Futurists were perhaps the first to recognize this shift. Describing the “inauguration of the monument” as a “rendezvous of uncontrollable hilarity,” the artist Umberto Boccioni understood the significance of these sites solely in terms of their destruction. In freeing the present of the burden of the past, these acts of destruction were intended to elevate the experience of the monument to the level of art and in the process re-invite these sites to once again participate in history.

The reaction of Iraqi dissident Kanan Makiya (also known by the pseudonym, Samir al-Khalil) to the unveiling of Saddam Hussein’s Victory Arch in 1989 confirms this relation. Upon encountering the work, al-Khalil is prompted to contemplate not the victory over Iran that the site commemorates, but rather the moment when the statue will be torn down in the same way the statues of King Faisal and General Maude had been before it. One only has to look at the back history of larger-than-life media stagings of monument death that have worked their way into collective imaginary (the destruction of Dzerinsky’s statue, the Berlin Wall, and even the World Trade Center) to find the historical roots of this peculiar reversal whereby eradication becomes the primary means for a monument or artifact to take place. This interchangeability of presence and absence is a symptom of modern media’s penchant for the spectacular. Through an alliance with media, the duality of iconoclasm—its tendency to produce images in the process of destroying them—is amplified such that the ubiquity, endless reach, and temporal instantaneity of media networks grant the monument the capacity to achieve an extraordinary, if only momentary, (negative) presence.

From 9/11 to the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas, these conditions are the basis for a recurring characterization of iconoclasm as a means of flattening out of the temporal unevenness of global culture, an integration of spectacle that exemplifies what Harry Harootunian describes as the sudden appearance of a “noncontemporaneous contemporaneity.” According to Harootunian, this temporality functions as a kind of return of the repressed in which the past

has come back to haunt the present in the incarnate form of explosive fundamentalism fusing the archaic and the modern, the past and the present, recalling for us a historical déjà vu and welding together different modes of existence aimed at overcoming the unevenness of lives endlessly reproduced.4

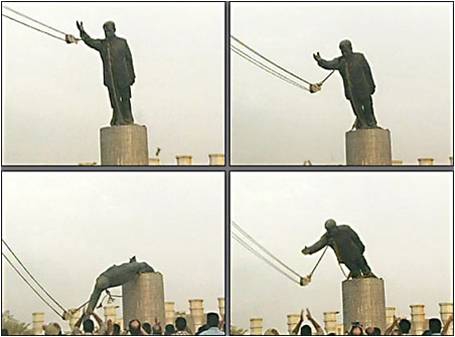

Acknowledging the way in which the conditions of contemporary mediality inform iconoclasm challenges the “Orientalist” binary of this characterization, which all too often assumes that these practices are somehow exclusive to Islam or the Middle East. The familiar refrains of “hijacking the spectacle” and the correlative discourse of “temporal unevenness” obscures the fact that not only does the Christian West have a long history of iconoclasm, but so do secular variations form a vital component of contemporary American military practice. Perhaps the most noteworthy example of this phenomenon occurred on April 9, 2003, when the U.S. forces attempted to rival the spectacle of 9/11 by orchestrating what was to be an equally cathartic shock to the symbolic order, the toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square in real time for an American audience.5 The effectiveness of this performance was contingent not only upon the sheer display of destruction but, more importantly, the ability of the image to oversee the productive aspects of the (re)activation that followed. Despite the infectious spontaneity of these images, we now know that the falling of the statue was anything but organic. In fact, the entire event was orchestrated by a “psychological operations team” of the United States Army.6 Recognizing the symmetry that structures this war of images, we might then ask similar questions of the performance in Mosul: How did these displays commandeer the mode of representation? To what extent was the productive aspect of iconoclasm managed and redirected through this relation? What role does the artifact have in this mode of image production? (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1. The toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, Iraq, April 9, 2003.

Available at Viscultblog.

In February 2015, ISIS released a video that showed militants destroying priceless artifacts from the region’s pre-Islamic era. Condemning the Assyrians and Akkadians as polytheists, the footage attributes the continued display of these artifacts to “devil worshippers” before a handful of men reduce them to dust with sledgehammers and power tools. Once the horror and disbelief waned, several observers began to raise questions regarding the veracity of this display. For those watching closely, the works seemed to fall apart a little too easily. As they collapsed, their interiors appeared powdery white. In some cases, iron bars could even be seen inside the sculptures as they broke apart. After careful scrutiny, there seems to be a general consensus among experts that (at most) two of the statues destroyed in the video were authentic—The Winged Bull and the God Rozhan. The rest were most likely copies. Yet, the video presentation of these events goes to great lengths to project an air of authenticity around this performance, and for the casual YouTube viewer the footage is undeniably convincing. Not only do the scenes take place inside of the occupied museum in Mosul, but so too does the footage begin with a montage of the actual wall placards that display the dates and titles of the works, all of which seems to confirm the historical provenance of the pieces that are about to be destroyed. As these perfect replicas tumble off the original plinths of the museum, the illusion becomes reality. (Figs 2 and 3)

Fig. 2. Still from an ISIS video showing the apparent destruction of ancient artifacts at Mosul Museum, February, 2015.

Available at Vice.

Fig. 3. Still from an ISIS video showing the apparent destruction of ancient artifacts at Mosul Museum, February, 2015.

Available at Times.

The events in Mosul clearly exemplify iconoclasm’s recent shift of emphasis from artifact to image. They would also seem to indicate a dwindling significance of the target’s status as original in this media-dependent configuration. However, a closer look at the intricacies of this particular staging calls this latter point into question. Mainstream media accounts have largely ignored the fact that the spectacle of destruction that took place in front of the camera was accompanied by more localized performances in which the originals were publicly escorted out-of-frame, so to speak. As Arif Hamdan, a history teacher in Mosul, explains, the people of the city were made aware that not only had the statues been taken to Syria (others have suggested they were taken to the Baghdad museum), but that manufactured copies had subsequently been shipped to the museum in Mosul not long after. As Hamdan explains, these “counterfeit statues” came from the Wadi Iqab neighborhood where they were “confiscat[ed] from one of the shops in the industrial area where many artifacts are being manufactured.”7 For those residents privy to the truth about the spectacle in the museum, the original continued to operate as the centerpiece of meaning, albeit from a safe distance.

Utilizing the contrast between this highly localized narrative and the global narrative that quickly took shape, the performance attempted to forge subjectivity around a kind of oppositional group identification. These tensions between local and global networks were placed in the service of what Carl Schmitt described as the “friend-foe” distinction such that “Muslim” identity would in large measure be defined by its distinction from a Western, non-Muslim other.8 It seems reasonable to conclude that it is this attempt at the creation of a singular and coherent collectivity that was the goal of this performance as much as the endangerment or destruction of the region’s artifacts. Such a conceit is made possible by iconoclasm’s incestuous relationship to the image. After all, it is the deployment of video and the layering effect that it produced between audiences that allowed the ambiguity of the original to be put to ideological work, despite being out of view.

Related Material:

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Thomas Stubblefield, “Iconoclasm beyond Negation: Globalization and Image Production in Mosul,” Aggregate 4 (December 2016), https://doi.org/10.53965/KZWN2741.

- 1

For a discussion of the way in which the theological base of spectacle and iconoclasm morphs into the secular context of late capitalism, see Marie-José Mondzain’s work Image, Icon, Economy: The Byzantine Origins of the Contemporary Imaginary (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006).

↑ - 2

W. J. T. Mitchell, Cloning Terror: The War of Images, 9/11 to the Present (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011), 3.

↑ - 3

Richard S. Nelson and Margaret Olin, Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 205.

↑ - 4

Harry Harootunian, “Remembering the Historical Present,” Critical Inquiry 33.3 (Spring 2007): 475.

↑ - 5

I discuss the events of Firdos Square in greater detail in chapter four of my book, 9/11 and the Visual Culture of Disaster (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2015).

↑ - 6

David Zucchino, “Army Stage-Managed Fall of Hussein Statue,” Los Angeles Times, July 3, 2004.

↑ - 7

Sarbaz Yusuf, “ISIS Transferred Original Monuments Abroad, Destroyed Fake Ones in Mosul Video,” ARA News, March 4, 2015, accessed September 2, 2016, http://rt.com/news/240801-isis-destroy-statues-fake/.

↑ - 8

Carl Schmitt, The Concept of the Political, trans. George Schwab (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007).

↑