Walking as Knowing and Interfering

“A photo in Der Spiegel shows a dark thunderstorm approaching the Hungarian Parliament. The message is clear: Twenty years after the collapse of communism, Hungarians are witnessing the end of yet another political era—the era of liberal democracy.”

Deutsche Presse-Agentur.Introduction

Liberal democracy is often conceived as a universal model of governance that — similar to the German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s funny and frightening thought experiment called the Pneumatic Parliament®—can be installed in any place, at any time. The core of Sloterdijk’s thought experiment is “a parliament building that is quick to install, transparent, and inflatable; it can be dropped in any grounds and then unfolds itself. In a mere one and a half hours, a protective shell for parliamentary meetings is ready, and within the space of twenty-four hours, the interior ambience for these proceedings can be made as comfortable as an agora.”1 According to Sloterdijk’s fictional product description, this hemispheric structure would have the capacity to seat 160 parliamentarians, who—thanks to advanced German engineering and the reliable delivery service of the US Air Force—could already make speeches, ask questions, and vote a day after the airdrop.

In contrast to Sloterdijk’s imagined product, existing parliaments are hardly ever “pneumatic.” They possess materialities and histories that complicate the ideal of inflatable democracy. The Hungarian Parliament, for example, took 100 years to gestate and another 20 years to be built. When opened in 1904, it was the largest parliament building in the world, and its first 100 years saw the rise and fall of fascism and communism. What would happen if we tried to understand what liberal democracy was in the 19th century, what happened to it in the course of the 20th century, and how it is being re-appropriated in the 21st century through such a building?

This was the central question of my PhD research at the Department of Sociology at Lancaster University. I started my research in 2006, and between 2008 and 2010 spent long periods in Budapest studying how the Hungarian Parliament worked as the “common-place” of democratic politics in Hungary.2 The ethnographic and historical research was inspired by Science and Technology Studies (STS) in general, and laboratory studies in particular.3 The strategy of focusing on places and material practices worked well, except that I could not pull the “naïve outsider” trick, as promoted by many STS scholars. No matter how hard I tried to convince my respondents that as a researcher from Lancaster I knew absolutely nothing about that big building on the east bank of the Danube, I was always perceived as a Hungarian citizen—and not a very well-informed one at that.

The following short texts, called “Walks,” are not so much about the Hungarian Parliament building. Rather they face up to the profound methodological tension that arose during my fieldwork between the figure of the researcher and the citizen. How can we know such a place as a parliament, and what does it mean to know it well? How to reconcile—or at least make visible—the differences between scientific and political ways of knowing and doing? The purpose of publishing these walks in Aggregate is to think across disciplines about the figure of the researcher-citizen, with applicability to sociologists and architectural historians alike.

To put it somewhat differently, these texts are about the fine mechanisms of political subjectification, addressed by many Foucauldian scholars but narrated exceptionally well by W. G. Sebald in Austerlitz and The Rings of Saturn.4 Using the English countryside as a point of departure, Sebald’s writings often took the form of semi-fictional walks that created a sense of co-presence of seemingly distant places and events. As one commentator put it, Sebald “transform[ed] history from a time-line that allows us to leave catastrophes behind into a building where they still exist in different spaces; where, in some sense, they are still happening, so that the survivors and their descendants are condemned to wander from one to another.”5 This may come across as a pessimistic approach, but Sebald’s texts are not just tools for knowing places; they are also devices for interfering with them. By piling fragments of stories about the past on top of each other, Sebald’s stories help reconfigure conditions of possibility for the present.

In this vein, my intention with the semi-fictional walks that follow is to capture not only the ways in which the political events of the past 100 to 150 years continue to leave traces on the Hungarian Parliament—and through that on Hungarian citizens—but also how they allow us to transform certain mechanisms of political subjectification. In other words, to practice critique.

Walk 1: Mediated by Memory

It’s early Monday morning and the weather is miserable. Everything is gray and damp; the wind is blowing leaves against my bedroom window. It feels as if I’m still in Lancaster, getting ready for another day on campus. But I’m in Budapest, in the apartment that used to be my home, and today is the first day of my fieldwork. To make things more complicated, the workers of the Public Transport Company have decided to go on strike, turning the city into one large traffic jam. In my otherwise silent room, I hear a constant murmur of car engines, occasionally interrupted by the sound of horns, and wonder how I will ever make it to the Parliament, which is in the middle of Pest, on the other side of the Danube. I have an important meeting to attend there in an hour and, by the sound of things, calling a taxi would be pointless. My only option is to ignore the rain and walk. From experience I know it takes about 45 minutes to get to the Inner City, so I hastily put on my working clothes (dark suit, plain shirt, no tie) and prepare my ethnographic toolkit for the day: two notebooks, several pens and pencils, a voice recorder, a digital camera, spare batteries, and a bottle of water. A few minutes later, I close the front door behind me, and start walking downhill, past long lines of cars heading to the center. After 15 minutes, I reach the main wharf in Buda. Here, the traffic is even worse than in the smaller streets. Everyone is driving in the same direction while the suburban rail tracks on the left side of the road are completely empty. The bus stops on the right side of the road are empty, too. There is something eerie about the whole scene. As I look around, I realize that I’m the only person walking, and I can’t decide whether it is the absence of the public transport that I find so disturbing or the absence of the public as such.

“As I look around I realize that I’m the only person walking, and I can’t decide whether it is the absence of the public transport that I find so disturbing or the absence of the public as such. In the distance, beyond several rows of lampposts and cables, I suddenly spot the Parliament.”

Author’s photograph.

In the distance, beyond several rows of lampposts and cables, I suddenly spot the Parliament. Its tall turrets and even taller cupola are barely visible in the rain, but still, what a huge building! Nothing around me matches it in size or grandeur. What does it look like? An enchanted castle? A cathedral? The Palace of Justice in Brussels? The Palace of Westminster in London? I have seen it so many times, even used its library every once in a while as an undergraduate, but only thought of studying it in the first year of my PhD. While walking towards Margaret Bridge I’m trying to remember all the things I’ve read and heard about the Parliament, but my research object seems too elusive, too intangible—a dark-gray structure in a light-gray setting. It couldn’t be more different from the building featured on the cover of various travel guides to Budapest and Hungary. The walls of that Parliament are always bright white, its roof is always terracotta brown, and the Danube in front of it is always blue, like in Johann Strauss’s famous waltz. That Parliament is an icon, a brand, similar to the Sydney Opera House or the Eiffel Tower—something that tourists can instantly recognize and photograph when they go for a stroll in the city.

“The Parliament is an icon, a brand, similar to the Sydney Opera House or the Eiffel Tower—something that tourists can instantly recognize and photograph when they go for a stroll in the city.”

Inner cover of author’s own passport.

It would be an exaggeration to call it a proper industry, but there is a Parliament Café down the road, and a Hotel Parliament, and I’ve come across all sorts of Parliament-related souvenirs, from T-shirts and postcards to bronze ashtrays and miniature glass models that rotate and glow purple in the dark. As I reach the bridge and climb the stairs to cross the river, I realize the scene in front of me is familiar not only from tourist brochures and guidebooks, but also from my old Hungarian passport. I remember the inner cover had an etching, showing the Parliament from the very spot where I’m standing now: a symbolic institution that all Hungarians can be represented by and represented with. At least that used to be the case. Not long after Hungary joined the European Union in 2004, a new passport was introduced. When I got mine, I discovered that, in the name of harmonization, most design elements have changed—including the inner cover, which now shows the Royal Palace in the Buda Castle in burgundy red. It also has new security features, for instance, a contactless chip with biometric data, enabling me to travel freely as a Hungarian and a European citizen. Budapest has never been so close to Lancaster; Lancaster has never been so close to Budapest. I like my EU passport, although I still don’t understand why the old etching had to go. It doesn’t matter, I guess. The Parliament and the Royal Palace might have very different political connotations, but as far as UNESCO is concerned, they belong to the same World Heritage Site called “the Banks of the Danube.”

“Halfway between Pest and Buda, between Belgrade and Vienna, between East and West, I stop for a moment to look around.”

Author’s photographs.

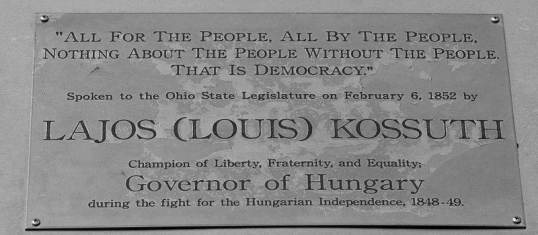

Halfway between Pest and Buda, between Belgrade and Vienna, between East and West, I stop for a moment to look around. From here I have a great view of the parliament building, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, the Chain Bridge, Gellért Hill with the Citadel, and the Buda Castle—the entire landscape is part of the world heritage! Well… almost. The office building on my left is not likely to be recognized as a site of “outstanding universal value.” The White House, as it is known in Budapest, was built after the Second World War. In the darkest years of the Stalinist dictatorship, it functioned as the headquarters of the much feared and hated State Protection Authority. Not long after the 1956 revolution it became, and until 1989 remained, the central office of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. Today, the building belongs to the National Assembly—this is where most Members of Parliament and Standing Committees are located. I have an appointment here later in the afternoon, but now I have to concentrate on the meeting that begins in 15 minutes in the main building. I leave Margaret Bridge behind and at the zebra crossing I notice a signpost with the names of several tourist attractions in English. Three of these—the Parliament, the Museum of Ethnography, and the Statue of Kossuth—are right next to each other, in a square named after the 19th-century politician Lajos Kossuth. He was governor-president of Hungary, and leader of the 1848–49 revolution and anti-Habsburg war for independence. After the Austrian and Russian forces defeated the Hungarian army, he took refuge in the Ottoman Empire, then in Britain, and then in the United States. There, he was warmly welcomed as one of the pioneers of democracy—a political concept he defined a decade before Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address” as “government of the people, by the people, and for the people.”

“In North America, Kossuth was welcomed as one of the pioneers of democracy—a political concept he defined a decade before Lincoln’s ‘Gettysburg Address’ as ‘government of the people, by the people, and for the people.’” Sign for Kossuth Road in Cambridge, Ontario, Canada.

I read somewhere that there is a Kossuth County in Iowa, and several towns bear his name in Mississippi, Ohio, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. It is not surprising, then, that every settlement in Hungary has at least one street or square named after him, not to mention all the cinemas, schools, sports clubs, and radio stations. But Kossuth Square in Budapest is a special place. There’s a very high concentration of public institutions in the area: The Parliament, which occupies the center of the square, is surrounded by the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Justice, the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, and the Museum of Ethnography, to name just a few. Since the end of the 19th century, this is where the most important political celebrations and demonstrations take place, often with the participation of hundreds of thousands of people. The First Republic was proclaimed here in 1918, and so were the Second Republic in 1946 and the Third Republic in 1989.

Kossuth Square in Budapest: “Since the end of the nineteenth century, this is where the most important political celebrations and demonstrations take place, often with the participation of hundreds of thousands of people. The First Republic was proclaimed here in 1918, and so were the Second Republic in 1946 and the Third Republic in 1989.”

József Balaton, Hungarian Press Agency (Magyar Távirati Iroda).

On October 23, 1989, to be precise. I was in school that day, as was every other 10-year-old in the country, sitting in one of my first history classes, when around noon the head teacher rushed in and told us to go to the main corridor, where hundreds of other school kids had already been waiting. After a few moments several television sets were turned on, so that we could virtually join the crowd in front of the Parliament and witness the fall of communism in real time. I remember interim President Mátyás Szűrös standing on one of the balconies above the main entrance, declaring Hungary a free and democratic republic. I also remember watching footage of joyous crowds in Berlin and Prague a few weeks later. And then those shocking reports about the Romanian revolution during the Christmas break. The Brandenburg Gate behind the remnants of the Berlin Wall; Václav Havel giving a speech in Wenceslas Square; Elena and Nicolae Ceaușescu tried and executed in a military compound outside Bucharest. These are my earliest memories of the political transition in Central and Eastern Europe, and now that I’m standing at the Parliament, trying to catch my breath after my unplanned morning walk, the blurry images in my head start gaining a new significance. They slowly transform into data, material to work with, along with various digital photos, voice recordings, interview transcripts, ethnographic notes, official documents, brochures, newspaper clippings, and an amorphous body of academic literature. In one way or another, they are all related to my research object, but how they might hang together is far from obvious.

Walk 2: Strolling as Pilgrimage

I’m waiting patiently in line at the Parliament, on the right side of the main entrance, next to a black obelisk. A flame is dancing on the top, and the stone around it looks melted, as if the obelisk were made of wax, not of granite. This is the Flame of the Revolution—the revolution of 1956, which was a nationwide revolt against the Soviet-type political regime. It started on October 23 as a student demonstration at the Budapest Technical University, but soon various groups of workers joined in, and by the time the march reached the Parliament, a crowd of 200,000 demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops, the resignation of the communist government, and free democratic elections. When, as a response, in a radio broadcast the First Secretary of the Hungarian Workers’ Party labeled the demonstrators the people’s enemy, events got out of control: In the evening, the statue of Stalin was toppled in the City Park, followed by deadly clashes between a group of protesters and the State Protection Authority at the radio headquarters. Early the next day, Soviet tanks appeared in the streets of Budapest, but the Russian soldiers seemed reluctant to intervene in what they initially saw as an internal political conflict. A few of them even changed sides and on October 25 joined the demonstrators at the Parliament. Draped in Hungarian flags they might have thought the worst part of the revolution was over, when all of a sudden a shooting broke out and bullets began to rain from the rooftops surrounding Kossuth Square. Although it only lasted for 10 minutes, the massacre left almost 100 people dead and many more injured. The crowd panicked—some tried to escape through the narrow streets south of the square, while others wanted to take cover in the Parliament, but the guards didn’t let them in.

Kossuth Square in 1956 and in 2006: “The massacre on October 25 was one of the darkest episodes of the 1956 revolution. Until the collapse of communism, it was an event no one dared to discuss, let alone commemorate, in public.”

Sándor Bojár, Hungarian Press Agency (Magyar Távirati Iroda); author’s photograph.

This was one of the darkest episodes of the 1956 revolution, suppressed in less than two weeks by the Soviet Army. Until the collapse of communism, it was an event no one dared to discuss, let alone commemorate, in public. Since 1990, October 23 is a National Day—on that day the black obelisk on my right becomes a central site of pilgrimage, surrounded by tea-light candles, white flowers, and people more somber-looking than those waiting around me for the next English-language Parliament tour. The elderly couple at the front of the queue is, I think, Italian; the family behind them must be from the United States; there’s another family from a Spanish-speaking country; the group of women behind me might be from Ireland, but I’m not sure. We all got our tickets half an hour ago, and were told to wait at the Flame of the Revolution until a tour guide arrives. There he is! Our guide greets us and explains that in order to get inside the Parliament we must go through a security check similar to a normal airport procedure. He turns around and we follow him to the nearest gate. In the meantime, I switch off my mobile phone and put it in my pocket. As I enter the building I place my jacket on a conveyor belt on my right. I then walk through the metal detector, pick up my jacket, and wait for the rest of the group to arrive. Slowly, we gather at the bottom of the main staircase and the tour guide begins his well-rehearsed talk. He points at a replica of the Parliament, made of 100,000 matchsticks by a Hungarian couple in the 1960s, and tells us that the building’s symmetrical structure reflects the bicameral system of the 19th-century National Assembly.

“A replica of the Parliament, made of 100,000 matchsticks by a Hungarian couple in the 1960s.”

Author’s photograph.

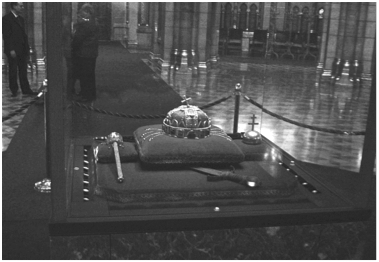

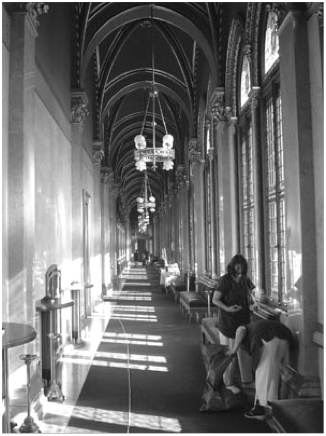

In the center, the Cupola Hall used to have a special political function: that’s where members of the House of Representatives and the House of Lords used to hold their joint sessions. Soon after Hungary’s German occupation in 1944, however, the House of Lords dissolved itself. Since then, the National Assembly is a unicameral institution, which means the Cupola Hall no longer plays a role in the legislative process. It’s more like the spiritual heart of the building, the guide says, with the Holy Crown in the middle. That’s where we’re heading, but first we need to climb a flight of stairs, which gives us enough time to marvel at the stained-glass windows, the massive granite columns, the golden decorations, and the painted ceilings of the main hall. I feel as though I am in a cathedral, and that’s exactly how the architect Imre Steindl wanted me to feel. In the original design description he referred to the parliament building as the Temple of the Constitution, and I’m sure both he and his political ally, Count Gyula Andrássy, would have been pleased with the result had they lived long enough to attend the opening ceremony. Steindl’s bronze bust is in a niche on the left side of the staircase and Andrássy’s name appears on one of the two marble slabs near the Cupola Hall. The other marble slab contains the full text of Act VII of 1896, the law that commemorates the conquest of the homeland, but the group’s attention is now shifting from the building to the most important relic of this profane shrine: the Holy Crown.

“The Holy Crown was too big for Charles IV’s head and almost fell off during the coronation ceremony in 1916. Bad omen—no wonder his empire fell apart two years later.”

Author’s photograph.

We’re asked not to use a flash, so I’m trying to take a picture in the dim light before everyone gathers around the glass cabinet, cordoned off in the middle of the hall. Inside the cabinet is the Holy Crown, sitting on a red velvet cushion, between the Sceptre and the Orb. Underneath is the royal sword. The cross on the top of the crown is crooked—no one knows why, our guide admits. The damage might have happened under the Habsburg rule, or even before that, during the Ottoman occupation of the country in the 16th and 17th centuries. The crown itself is much older, one of the oldest in Europe. It is said to be the one St. Stephen, Hungary’s first Christian king, was crowned with in 1000 AD. According to a popular legend, it was a gift from Pope Sylvester II—a formal acknowledgment of Hungary as an independent kingdom wedged between the Holy Roman Empire in the West and the Byzantine Empire in the East. Its “holiness” refers to the strange fact that unlike everywhere else in Europe, in Hungary it was the crown that had a king and not the other way round. The last monarch to wear it was Charles IV, the grandnephew of Francis Joseph. Contemporary photographs show that the Holy Crown was too big for his head and almost fell off during the coronation ceremony in 1916. Bad omen—no wonder his empire fell apart two years later. In the interwar period, the royal jewels were held in the Royal Palace in the Buda Castle, and for decades after the Second World War they were kept in the US gold reserve at Fort Knox. In 1978, they were returned to Hungary and put on display in the National Museum until 2000, when a conservative government decided to celebrate the thousandth anniversary of St. Stephen’s coronation by transferring the regalia to the Cupola Hall of the Parliament. What exactly a royal symbol has to do in the legislature of a republic is something many people find puzzling, but the Holy Crown is not the only anachronistic object in the Hungarian Parliament. As our group proceeds from the Cupola Hall to the former House of Lords, our guide tells us a fascinating story about what turn out to be cigar holders all around the debating chamber.

“To prevent any dispute about which Cuban belonged to whom, each slot in the cigar holders was numbered, allowing Hungary’s greatest men to return to their stub between two sessions.”

Author’s photograph.

These days, smoking is not permitted in the corridors, but when the building was built, most Members of Parliament smoked—and often they smoked the same brand of cigars. To prevent any dispute about which Cuban belonged to whom, each slot in the cigar holders was numbered, allowing Hungary’s greatest men to return to their stub between two sessions. Unintentionally, these objects came to be used as sophisticated devices measuring oratory skills: the longer the ash in the end of the cigars, the better the speech in the chamber. I’m trying to imagine what this place must have looked and smelled like 100 years ago, before Hungary entered the First World War and, consequently, lost two-thirds of its territory, but soon the imaginary smoke is gone, and so are the lords. We are reminded that this part of the building is now defunct—it can be rented for conferences and public events, but currently serves no political purpose. However, since the debating chamber in the House of Lords is almost identical to the debating chamber in the House of Representatives, it’s a perfect place for our guide to explain how today’s political system works. For about 10 minutes, he talks about the logic of general and municipal elections, the difference between political parties and party factions, the seating order in the debating chamber, the roles of the Speaker and the President of the Republic in the legislative process, but the visitors’ box where we’re standing is too small for all of us and it’s difficult to follow everything he says.

“After the mini lecture, someone asks what the difference is between the Irish and the Hungarian political systems, but I can’t hear the answer because the rest of the group begins to leave the stuffy box.”

Author’s photograph.

After the mini-lecture, someone asks what the difference is between the Irish and the Hungarian political systems, but I can’t hear the answer because the rest of the group begins to leave the stuffy box. I go with them and wait for our guide to reappear from the House of Lords and lead us to the exit. This is the end of our tour, he says a moment later, and we applaud him. Then we walk to a dark and narrow staircase in the end of the corridor—it’s very different from the one we took earlier to get to the Cupola Hall. On the way out, we pass by a couple of offices. I hear a telephone ringing, but before anyone can answer it we’re outside, in the fresh air, beyond the chain separating the Parliament from Kossuth Square and the rest of Budapest. I see several groups of tourists waiting beside the Flame of the Revolution, and hear a tour guide explaining the security procedures in German.

Walk 3: Socialist Dream World

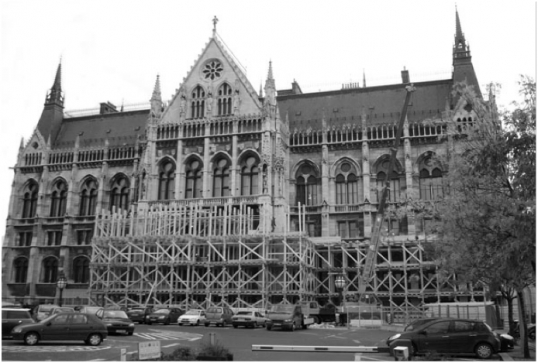

I’m walking to the Parliament to get my permanent pass—a chip card that will let me enter the building whenever I wish. A few months ago, I wrote an email to the Office of the National Assembly, introduced myself and my PhD research in Lancaster, and asked whether it was possible to spend some time with them to learn more about their work. In their response, they said that they were looking forward to having me, but regretted to inform me that my visit would coincide with the arrival of the new interns, and so they wouldn’t be able to provide an office space in the main building. I assured them that it wasn’t a problem, since what I wanted to do was closer to organizational ethnography than to desk research—all I needed was access to the Office and its employees. In turn, I was asked to fill out an electronic form and send it back, along with a digital photo of myself, so that my request for a permanent pass could be processed. This I did well before I came to Budapest, and also gave the Office my mobile number, just in case they wanted to contact me. Earlier today I got a call saying that my permanent pass was ready to be picked up from the Secretariat, but in order to get it I had to enter the Parliament with a day pass, which would be waiting for me at the reception desk of Gate XVII. It turns out to be one of the side entrances on the northern side of the building. I’m about to pass a barrier separating the Parliament’s parking lot from Kossuth Square when a guard stops me and asks if I’m looking for the tourist entrance. No, I say proudly, I have a meeting at the Office of the National Assembly. He asks for my identification card and withdraws into his small watchtower to check on his computer if I’m in the system. I am, indeed! He returns my ID and tells me to proceed to the nearest gate, which is currently hidden behind scaffolding.

“If all goes according to plan, most traces of the twentieth century (shrapnel and bullet holes, soot, and damage caused by acid rain) will disappear by the end of 2012.”

Author’s photograph.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen the Parliament without wooden planks and metal poles around one part or the other. In a recent newspaper article, I read that the House of the Nation has been under permanent reconstruction since the end of the Second World War. Like most buildings in the area, it was heavily damaged in the siege of Budapest, and the most important task in the second half of the 1940s was to fix the safety hazards and ensure the proper functioning of the institution. In the 1950s the interior decoration was repaired, followed by the Kossuth Square façade in the 1960s and the cupola in the 1970s. The complete renovation of the river façade began in the late 1980s and took almost 20 years to finish. Now it’s the northern side’s turn. If all goes according to plan, most traces of the 20th century (shrapnel and bullet holes, soot, and damage caused by acid rain) will disappear by the end of 2012. The new stones will be impregnated with a special smog-repellent material, and are expected to last for at least 100 years. After a short detour through the parking lot, I reach the side entrance and pick up my day pass. It works much like an Oyster Card on the London Underground: I “touch in” and the doors open automatically. I enter the Parliament, but before I continue my way to the Secretariat I have to go through a security check. I put my backpack and my jacket on a conveyor belt and pass through a metal detector gate—no beeps. I then turn right and take an elevator to the first floor. Contrary to my expectations, the long corridor next to the former House of Lords looks empty. There are no politicians chatting in small groups, no bureaucrats rushing up and down with papers in their hands, no tourists marveling at stained-glass windows. The only people I meet before I cross the Cupola Hall are two cleaners in uniforms. As I walk past them, I try to imagine how much effort it takes to keep this place neat and tidy.

“Dozens of bins to empty, hundreds of windows to clean, thousands of carpet-meters to vacuum… . A task beyond human capacity.”

Author’s photograph.

Dozens of bins to empty, hundreds of windows to clean, thousands of carpet-meters to vacuum. And that’s only one fragment of general maintenance. A small army of plumbing and heating engineers, electricians, gardeners, carpenters, and technicians must be required to look after the building. A task beyond human capacity, one could say, and it wouldn’t be completely off the mark. I heard from someone who used to work here that in order to prevent pigeons from using the Parliament as a shelter, the Department of Repair and Maintenance decided to keep trained falcons in the inner courtyards. For a while it seemed to work quite well, but over the years the pigeons have gotten smarter. Instead of exposing themselves by flying from one corner of the building to the other, nowadays they just amble along the walls and the windowsills—to the great annoyance of everyone whose office faces one of the inner courtyards. Those working in the Secretariat can consider themselves lucky: Their main office faces the Danube and the Buda hills. I knock on the large wooden door, enter the room, and introduce myself to the Head of Secretariat. It turns out she’s the one who called me in the morning and emailed me about the electronic form when I was still in Lancaster. After chatting a bit about my research, she gives me my chip card and congratulates me on becoming an “expert”—that’s my official status in the Parliament’s Information System. Once again, she apologizes for not being able to accommodate me in the main building, but says I could use a desk in the Information Center for Members of Parliament if I wanted. In fact, she has already arranged a meeting for me with the Head of the Center and another one with the Secretary General of the Office of the National Assembly. The first is in 20 minutes; the second is at 9 a.m. on Wednesday. She’s great! I thank her for her help and ask how to get to the Information Centre. She says it’s on the top floor in the White House, just a few minutes’ walk from here. I leave the Secretariat, and on the way out I return my day pass at Gate XVII. After crossing the parking lot, I go to the wharf and walk along the river until I reach the H-shaped building at the foot of Margaret Bridge. This is where the offices of most Members of Parliament, party factions, and standing committees are located. From an organizational point of view the place I’m about to enter is simply an extension of the Parliament.

“From an organizational point of view, the White House is simply an extension of the Parliament. At the same time, it could just as well be called the Parliament’s Other.”

Author’s photograph.

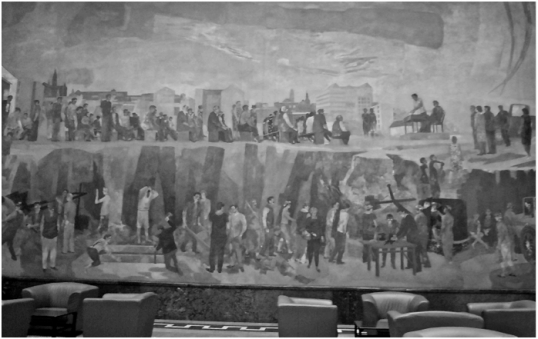

At the same time, it could just as well be called the Parliament’s Other. Its main architect, Gábor Preisich, was an important member of the modernist school in the interwar period. Strongly influenced by the Bauhaus movement, he and his colleagues designed several residential buildings in Budapest, including one with the city’s first purpose-built film theater on its ground floor. After the Second World War, Preisich played a significant role in the redevelopment of the ruined capital and got involved in a couple of highly prestigious projects—one of them was the construction of a new office for the Ministry of the Interior. The White House, as it came to be known, was opened in 1949, but soon after the communist takeover it became the headquarters of the State Protection Authority—the secret police force notorious for the systematic torture and imprisonment of thousands of people in the first half of the 1950s. During the 1956 revolution, the State Protection Authority was abolished and its property was returned to the Ministry of the Interior, only to be taken over by the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party in the early 1960s. For nearly three decades, the White House was used as the main office of the Party’s Central Committee, which means it was the effective center of power until the collapse of communism. In 1990, the Office of the National Assembly moved in, and their first task was to completely renovate the building. Most artifacts associated with the old regime (red stars, red flags, golden hammer and sickle emblems) were removed, but Aurél Bernáth’s Workers’ State, a socialist-realist secco that covers the entire back wall of the foyer, caused a real headache. There it is—I can see its bright colors from the main entrance. I show the guards my expert card, go through a security check, and walk straight to the painting.

“Too embarrassing to be left intact but not harmful enough to be destroyed”—Aurél Bernáth’s Workers’ State is a socialist-realist secco that covers the entire back wall of the foyer in the White House.

Author’s photograph.

It shows a socialist dream world divided into three sections. At the bottom I see all sorts of workers pulling and lifting and hammering things; in the middle there’s a mixed group of people sitting in rows, listening to two figures on the right; in the distance a modern city vanishes into the great open sky. Ideologically, there’s nothing wrong with the picture. Not a sign of oppression, coercion, or conflict; not a slogan glorifying the Party and the Leader; just more-or-less equal men and women minding their own business—hardly incompatible with the values of liberal democracy. Too embarrassing to be left intact but not harmful enough to be destroyed, in 1990 the Workers’ State was simply covered with a large velvet curtain. In 2004, a conservative Member of Parliament suggested that it should be replaced with a new painting commemorating Hungary’s joining the European Union; but after a long debate, the Cultural Committee of the National Assembly decided it was time to recognize the artwork for what it is and accept it as part of our cultural heritage. I’d like to spend more time in the foyer, but I realize it’s time to meet the Head of the Information Centre on the seventh floor, above the faction offices, so I turn right and call the elevator.

Walk 4: Secrets of Corridors

I’m on my way to the White House to meet Péter Gusztos, deputy faction leader of the Alliance of Free Democrats, and a friend of mine since undergraduate times. We studied sociology together in Budapest in the late 1990s, but Péter never graduated. He was too busy establishing a youth section for the liberal party, which I initially thought was an interesting but exceedingly time-consuming pastime, rather than the first stage of a proper political career. I was wrong. As president of the youth section called New Generation, Péter gradually made a name for himself in the party and played an active role in several media campaigns. In 2002—a few months before I finished my degree—he became one of the youngest members of the Hungarian Parliament. Despite his relative lack of experience, Péter played his cards right: In 2006, he was re-elected and then voted deputy faction leader of his party. I was already in Lancaster then, working on the outline of my PhD, which at the time was going to be a comparative study of political spaces in Hungary. Péter was the only person I knew who had access to the Parliament, so before finalizing my research plan I asked him if there was a chance he could show me around his workplace. He said it wasn’t a problem and, to my surprise, asked if I was also interested in accompanying him to various committee meetings and plenary sittings. I admitted that until then I had mostly been concerned with the architecture and infrastructure of liberal democracy, but observing him as he went about his business seemed like a great opportunity to learn about political representation in practice. After some negotiation with the faction, Péter agreed that for three weeks I could follow him wherever he went as a Member of Parliament—except for the party’s executive committee meetings.

“I feel like I’m being taken back in time: The foyer of the White House looks as if it still belonged to the People’s Republic.”

Author’s photograph.

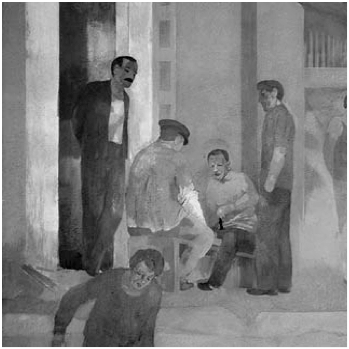

This was more than three months ago. Last time we spoke, Péter proposed that the research would begin today, in a café near the Parliament. He had a meeting scheduled for 9 a.m., so he said we would have plenty of time before that to discuss the program for the coming days. It sounded like a good plan, but that morning I got a text message saying that the meeting had been postponed, and since Péter had a few errands to run, he asked me to meet him in his office instead—there should be a pass waiting for me at the reception of the White House. I’m early, but I don’t want to wander around. I walk straight to the main entrance and tell the guards I’m looking for the faction office of the Alliance of Free Democrats. They ask for my identification card and check on their computer if I’m in the system. I’m recognized as Péter’s guest and get a day pass. As I go through the security check and leave the metal detector gate behind, I feel like I’m being taken back in time: The foyer of the White House looks as if it still belonged to the People’s Republic. The furniture, the lights, the marble columns—everything is strangely familiar. I recognize the secco covering the back wall from my last visit. A small metal plate in the corner says that the Workers’ State was painted between 1968 and 1970 by Aurél Bernáth. Recently, I read an interview with an art historian—she said what makes the secco unique and worth preserving is not the depiction of an idealized division of labor among workers, peasants, and intellectuals, but the individual characters, some of whom can be recognized as leading artists and politicians of the previous regime.

“It’s a curious image: In the Workers’ State, Kádár and his friends seem to be the only ones who are not working, learning, or doing anything politically relevant.”

Author’s photograph.

János Kádár, for instance, is in the upper left corner, playing chess, while the rest of the group is listening to a lecture. It’s a curious image: In the Workers’ State, Kádár and his friends seem to be the only ones who are not working, learning, or doing anything politically relevant. At the same time, what could be more politically relevant than winning the actual game? In Kádár’s case, the relationship between chess and politics was not simply metaphorical. One of his biographers claims he became a communist after reading a book by Friedrich Engels, given to him as a prize for winning a junior chess competition in the late 1920s. During the interwar period, he was an active member of the illegal communist movement, even served as First Secretary of the Hungarian Communist Party for a while, but his official political career really began here, in the White House, when he moved in as Minister of the Interior in 1949. It also ended here four decades later when, due to ill health, he resigned as General Secretary of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party. He died in the very same hour his main political victim, Imre Nagy, was rehabilitated by the Supreme Court. Kádár’s catafalque was set up in the foyer of the White House. To his comrades’ greatest surprise, tens of thousands came to bid farewell to him and his regime. Contemporary photos show the end of the queue was near the main entrance of the Parliament. Kádár’s office used to be on the first floor of the White House—he often complained it was too cold in the winter and too hot in the summer. In this regard, current Members of Parliament are much better off: Their offices are fully renovated and air-conditioned. Otherwise, their working environment is pretty unremarkable. The halls and corridors I cross could just as well be in a hospital, a hotel, or a university.

“The Members of Parliament’s working environment is pretty unremarkable. The halls and corridors I cross could just as well be in a hospital, a hotel, or a university.”

Author’s photograph.

Nothing suggests they belong to the National Assembly, except perhaps for a few party logos, indicating the factions’ location. The Alliance of Free Democrats is on the fourth floor, in one of the four legs of the H-shaped building. Unlike the socialists and the conservatives, the liberals don’t take up much space. Today, they are one of the smallest party groups in the Parliament, which is quite ironic given the crucial role they played in the establishment of the multiparty system at the end of the 1980s. They were perhaps the most radical participants of the National Roundtable, and had a good chance of winning the 1990 election. Although they narrowly lost to the Hungarian Democratic Forum, some of their members became prominent figures of the new regime. Writer and former political prisoner Árpád Göncz was elected President of Hungary; sociologist and samizdat-publisher Gábor Demszky became Mayor of Budapest—not a bad start for a young political formation. Political analysts believe things went astray after the 1994 election, when the liberals accepted the socialists’ offer to form a coalition. Why on earth did the fierce anti-communist Alliance of Free Democrats team up with the successors of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party? Were they so hungry for power? Or did they think it was their moral duty to keep a close eye on the new-old ruling party? Whatever the reason, by the end of the term they lost most of their voters, and it was already a considerable feat that they managed to cross the 5 percent threshold in the 1998 election. It’s been all downhill since then, despite the fact that the socialist-liberal coalition returned to power in 2002, and—after some years of stable economic growth and Hungary’s joining the European Union—won a mandate for another term in 2006. In government, ministers and state secretaries affiliated with the Free Democrats haven’t had much space for maneuvering: The socialists have often used them as scapegoats for failed reforms. This was exactly the case last week, when the Prime Minister unilaterally decided to sack the Minister of Health, blaming her for the highly unpopular transformation of the national health insurance system. This was too much for the liberal faction, and on Monday it announced it wanted to break up the coalition. Later that day, the party’s executive committee confirmed the faction’s decision and asked its members to resign from their government jobs. That was the beginning of the latest political crisis, and I’m dying to ask Péter about it—I just hope he won’t have to postpone the research altogether. I’m in front of the main faction office. The door is open, but the secretary tells me Péter’s not in yet. She jokingly asks if I’m the anthropologist she was told about, and I say, yes, I’m waiting for the deputy chief of the tribe to arrive. She laughs and offers me a seat in the corner. On a cupboard nearby I notice a cartoon that shows a cat in front of a mouse hole. The caption says: “You’re always on the run, we never have time to talk!” In a few minutes Péter arrives and apologizes for being late. Before I can say anything, he tells me we need to hurry to the Parliament—today’s plenary sitting is about to start. After discussing something with the secretary, he picks up a couple of documents from his desk and we leave the office. On the way downstairs I try to ask him about the coalition crisis, but we’re interrupted by a phone call. By the time the call is over, we’re out on the main wharf, walking towards Kossuth Square. Unexpectedly, Péter begins to talk about long-distance running: his morning exercise on Margaret Island, his personal records, and his plan to participate in several city marathons, including the ones in Berlin and in New York. I have no idea how to respond—this is not the conversation I expected. I’m so confused I don’t even notice the guards at the Parliament, and before I can find my day pass we’re already inside the building. As we walk past the former House of Lords, all of a sudden Péter begins to outline the program for the week. I can’t take notes, so I try to memorize as much as possible, but the list is long. Plenary sittings, committee meetings, discussions in the faction, media interviews, lunch with so and so, coffee with so and so. My head is spinning.

“The corridors of the Parliament, the Cupola Hall with the Holy Crown, the House of Representatives are all familiar, and yet everything is so different, so full of life.”

Author’s photograph.

The corridors of the Parliament, the Cupola Hall with the Holy Crown, the House of Representatives are all familiar, and yet everything is so different, so full of life. There are people everywhere: politicians, experts, journalists talking to each other or on their mobile phones. Péter tells me he needs to enter the debating chamber, but we can continue planning the week in the break. In the meantime, I should just go to the experts’ box and enjoy the show. I do as he says: I pull the heavy velvet curtain and find a seat in the back row.

Walk 5: The Rocky Road Ahead

In October 2009, I finished my fieldwork in Budapest and on my way back to Lancaster I decided to visit a friend in Berlin. At the time he was a post-doc at Humboldt University, and when I told him I was looking for a place for the writing-up period, he suggested that I get in touch with one of the professors at his department. This I did, and thanks to the professor’s and his colleagues’ generosity, in early 2010 I became a visiting researcher at the Institute for European Ethnology. Occasionally, I attend seminars and talks at the department, but usually spend my days on the fifth floor of the Grimm-Zentrum—Humboldt University of Berlin’s brand-new central library. Unlike the famous Staatsbibliothek in Potsdamer Straße, the Grimm-Zentrum is an open-shelf library, and I find it easier to lose my way among endless rows of bookshelves than Hansel and Gretel lost their way in the Ilsestein forest. Books are not the only distractions, though. On the first floor there’s a comfortable lounge surrounded by magazine stands, and often I start the day here by flipping through the latest newspapers. Normally, this morning ritual doesn’t last longer than half an hour, but today is different. Today is the day after the 2010 election in Hungary, and I feel obliged to carefully read every single report I can find on the topic. I’m not looking for the results—I know them very well by now. The conservative Fidesz got 68 percent of the seats, which means they will have a qualified majority in the new National Assembly; the socialists, who were in power in the previous two terms, came second with 15 percent, barely ahead of the far-right Jobbik with its 12 percent; the last party that got into the Parliament is a relatively unknown green party called Politics Can Be Different; the Alliance of Free Democrats was nowhere near the magic 5 percent threshold.

“A photo in Der Spiegel shows a dark thunderstorm approaching the Hungarian Parliament. The message is clear: Twenty years after the collapse of communism, Hungarians are witnessing the end of yet another political era—the era of liberal democracy.”

Deutsche Presse-Agentur.

What I’m looking for is the commentaries in the German newspapers. I don’t have to search for them for too long. In Die Tageszeitung, a journalist observes that Hungary turned into “a grubby hive of nationalism”; while in Tagesspiegel, another journalist reckons the 2010 Hungarian election proves that political structures in Central and Eastern Europe are just not stable enough. A photo in Der Spiegel shows a dark thunderstorm approaching the Hungarian Parliament. The message is clear: Twenty years after the collapse of communism, Hungarians are witnessing the end of yet another political era—the era of liberal democracy. As I’m reading the articles, I feel shame and anger. I’m deeply ashamed because of the increasing strength of the far-right, the incompetence of the socialists and the liberals, and the uninhibited populism of the conservatives. At the same time, I’m angry because of the haughty treatment of Hungary in the press. If the outcome of a free and fair election can be interpreted as the end of democracy, then surely it is the concept of democracy that requires some reflection, not the people and their preferences. This is more or less what I told Péter when I saw him last week. He was in Berlin to run the half-marathon, and after the race we met for a coffee. Since the end of my fieldwork, this was the first time we got to talk about Hungarian politics, and I was eager to hear his thoughts about the election. To my surprise, he had nothing to say. A few months ago, Péter decided not to run for re-election, and so he had not been involved in the campaign at all. After the breakup of the socialist-liberal coalition, the Alliance of Free Democrats struggled to find its place in the National Assembly: Some members of the faction wanted to re-establish the ties with the socialists while others demanded the complete replacement of the party leadership. Internal conflicts were getting more and more bitter, and when in the 2009 European Parliament election the liberals failed to win any seats, the party fell apart. That was when Péter realized he had to come up with a Plan B. He thought it was time that he returned to university and finish his degree, and maybe establish a sports foundation for children with disabilities. When I asked him whether one day he wanted to return to politics, he said in eight years he’d still only be 42. I didn’t quite get what that meant, but now it was his turn to ask difficult questions. He was curious to know what the outcome of my PhD research was. I told him I couldn’t possibly summarize it in a sentence, but I could share a real discovery, which I thought captured very well what my research problem was. While browsing around in the Grimm-Zentrum, I found two kinds of books with images of the Hungarian Parliament on their cover. One was about the development of Budapest in the second half of the 19th century, and the parliament building was used as an outstanding example of a series of projects realized between the signing of the Austro-Hungarian Compromise and the outbreak of the First World War, while the other had something to do with the current political system, initiated in 1989–1990. In the first case, there was materiality, but absolutely no reference to contemporary politics, while in the second case, there was plenty of politics, but the 100-year-old building—along with other artifacts—remained practically invisible. The only exception I could find was a bilingual catalogue, published by the Museum of Fine Arts, which tried to hold materiality and politics together by presenting the Hungarian Parliament as the realization of a high-political program—a program that could just as well be called liberal democracy. If it’s true that there’s no liberal democracy without a parliament, I said enthusiastically, then examining the material practices of parliamentary politics might help us to understand how liberal democracy works and how it could work differently. Why would it have to work differently? Péter asked. Well, if the outcome of a free and fair election, for instance the recent one in Hungary, can be interpreted as the end of democracy, then surely the concept of democracy needs some rethinking. Péter looked unconvinced, and I got frustrated for not being able to say anything more useful or relevant to him. As I look at the newspapers scattered around me today in the lounge of the Grimm-Zentrum, the frustration returns and so I decide to go for a walk to clear my head. I go downstairs, turn right at the main entrance of the library, and follow a narrow passageway to Friedrichstraße.

“The steel-and-glass pavilion was built a year after the Berlin Wall for border clearance. It was known as Tränenpalast—the Palace of Tears—because of all the farewells it witnessed until 1989.”

Author’s photograph.

I want to walk directly to the Spree, but before I can reach the riverbank, I almost bump into a rusty metal column in the middle of the street. It turns out to be one of the memorials that were recently erected along the former border of the German Democratic Republic. One side of the column shows a map of Berlin divided into two parts, while another side contains a short description about the historical significance of the area. From this I learn that after the Second World War, Friedrichstraße station became the last underground station before the Western border. When the construction of the wall began in August 1961, the station was turned into a terminus and a border crossing point for travelers from both parts of the city. The steel-and-glass pavilion right in front of me was built a year later for border clearance. It was known as Tränenpalast—the Palace of Tears—because of all the farewells it witnessed until 1989. Since the fall of the wall, its façade remained largely unchanged and so, according to the column description, the pavilion today serves as one of the most striking reminders of the complex border system that separated the East from the West in the center of Europe. A large poster at the entrance says the Palace of Tears will soon be home to a permanent exhibition. I walk past the now empty building, and turn left on the riverbank to get to the other side of the station.

“After several rounds of debate, Foster came up with the idea of placing a massive steel-and-glass cupola right above the plenary chamber, emphasizing the transparency of the political system.”

Author’s photograph.

As I look up, in the distance I spot the Reichstag with Norman Foster’s cupola on the top. Another friend of mine, who is not only a German citizen, but also a trained architect, once told me that Foster’s initial plan was to erect an enormous canopy over the parliament building, placing the legislature literally under the same roof as the people, but many Members of Parliament insisted on having a dome that echoed the original design of the Reichstag. After several rounds of debate, Foster came up with the idea of placing a massive steel-and-glass cupola right above the plenary chamber, emphasizing the transparency of the political system. The plan was eventually approved, and the renovated Reichstag opened its doors in 1999. The dome quickly became a popular tourist attraction—an icon of reunited Germany and a symbol of liberal democracy. In the beginning of the new millennium, it appeared on the cover of dozens of political science and international relations textbooks and served as a model for such political structures as the City Hall in London and the Supreme Court in Singapore. As I walk closer to the German parliament building, Norman Foster’s dome begins to look a lot like Peter Sloterdijk’s disturbing thought experiment: the Pneumatic Parliament®.

Afterthought

What is liberal democracy? According to the textbook definition, it is an abstract model of governance that in the early 21st century appears to have no alternatives, at least not in the West. In the walks above, I have tried to outline a different definition, which takes actual places and material practices as its starting point. Taking inspiration from the site-specific analyses of Science and Technology Studies and the ficto-critical works of W.G. Sebald, I have tried to show that liberal democracy can be thought of as an ongoing process that mediates between collective histories and personal memories, expert knowledges and lay opinions, and a wide range of political sentiments, from awe to anger. Parliament buildings in this sense are not simply local manifestations of a universal and inherently immaterial model of governance, but the sites where such contingent mediation processes take place in a more-or-less coordinated fashion. Walking is not only a method of knowing such sites, but also a means of interfering with them.

Let me spell out what this means through the case of Hungary. Since the end of my research, and the election of the current government, the political space associated with Hungarian democracy has changed dramatically. Hardly anything I have described in my walks remains as it was during my fieldwork: The statue of Lajos Kossuth in front of the Parliament has been replaced, the black obelisk commemorating the 1956 revolution has been removed, a new visitors’ center has been opened, and the walls of the parliament building have been completely renovated. These changes coincided with the unilateral rewriting of the Hungarian Constitution, the replacement of most members of the Constitutional Court, the restructuring of the Public Service Broadcasting and the Hungarian Press Agency, the reformation of the internal workings of the legislature, along with the election law and many others. These were not haphazard changes but the systematic removal of the checks and balances that keep a democracy robust and resilient. Not surprisingly, looking at these transformations, numerous analysts and commentators, both in Hungary and abroad, have argued that Hungary is no longer a democratic country. My diagnosis is somewhat different. In the past five to six years, Hungary has become a bad democracy—a democracy that communicates there are no visions beyond the one propagated by the government.

The parliament building in the center of Budapest could be thought of as the manifestation of this vision. As I have tried to show, however, it could also be thought of as a repository of alternative visions. Walking is a process of detecting such visions, which are already present in such places as the Parliament, and making them more accessible. Walks, in other words, are not simply alternative descriptions or representations of places; they are alternative ways of performing places into being. Sometimes they resemble quasi-scientific travelogues with explicit references, but—as W. G. Sebald’s works show—mostly they work allegorically. Their truth claims rest not necessarily on replicability, as in the case of experiments, but on recognition.

Did you recognize the Hungarian Parliament in my walks? If you have never been to Budapest, you might not feel competent to answer this question. If you know Budapest well, you might say my walks are outdated. But you might still recognize the Hungarian Parliament as a political technology of subjectification that defines citizens as individuals who belong to a political community, who are knowledgeable about a wide range of issues, and who have a more-or-less coherent worldview. In my walks, you might recognize the tension not only between the researcher and the citizen, but also between the ideal citizen as defined by the Parliament and the actual citizen doing the walks inside and around the parliament building. You might recognize how personal memories interfere with official histories, how the outsides of the legislative machinery interfere with its insides, and how the figure of the voter interferes with other political figures including politicians. You might also recognize that these interferences are simultaneously frustrating and surprising. They open up new possibilities of practicing critique—not in opposition to, but within liberal democracy. At least this has been my hope.

Related Material:

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Endre Dányi, “Walking as Knowing and Interfering,” Aggregate 5 (June 2017), https://doi.org/10.53965/SAND4791.

- 1

Originally published in Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel, eds., Making Things Public: Atmospheres of Democracy (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Karlsruhe, Germany: ZKM/Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe, 2005). A German version is available online at http://www.g-i-o.com/pp1.htm.

↑ - 2

Laurent Thévenot, “Voicing Concern and Difference: From Public Spaces to Common-Places,” European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology 1, no. 1 (2014): 7–34.

↑ - 3

The literature is huge, but the most common references to laboratory ethnographies are Karin Knorr-Cetina, The Manufacture of Knowledge (Oxford, England; Elmsford, New York: Pergamon, 1981); Bruno Latour and Steve Woolgar, Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1986); John Law, Organizing Modernity (Oxford, UK; Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1994); Michael Lynch, Scientific Practice and Ordinary Action: Ethnomethodology and Social Studies of Science (Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993).

↑ - 4

W. G. Sebald, Austerlitz (New York: Random House, 2001); The Rings of Saturn (New York: New Directions, 1998). On Sebald’s influence on subjectification and modes of knowing, see Jacky Bowring, A Field Guide to Melancholy (Harpenden: Oldcastle Books, 2008); J.J. Long, W.G. Sebald: Image, archive, modernity (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2007); Christian Scholz, “‘But the written word is not a true document’: A conversation with W.G. Sebald on literature and photography,” in Searching for Sebald: Photography after W.G. Sebald, ed. Lise Patt and Christel Dillbohner (Los Angeles, CA: The Institute of Cultural Inquiry, 2007).

↑ - 5

Per Wirtén, “Where were you when Europe fell apart?,” Eurozine, December 22, 2011, http://www.eurozine.com/where-were-you-when-europe-fell-apart/

↑