The Design of the Nubian Desert

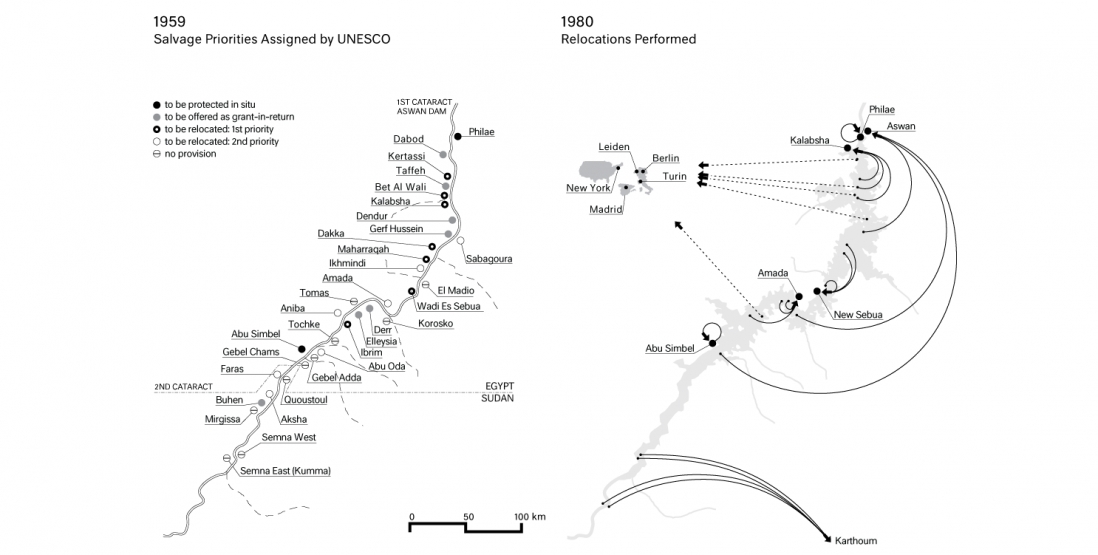

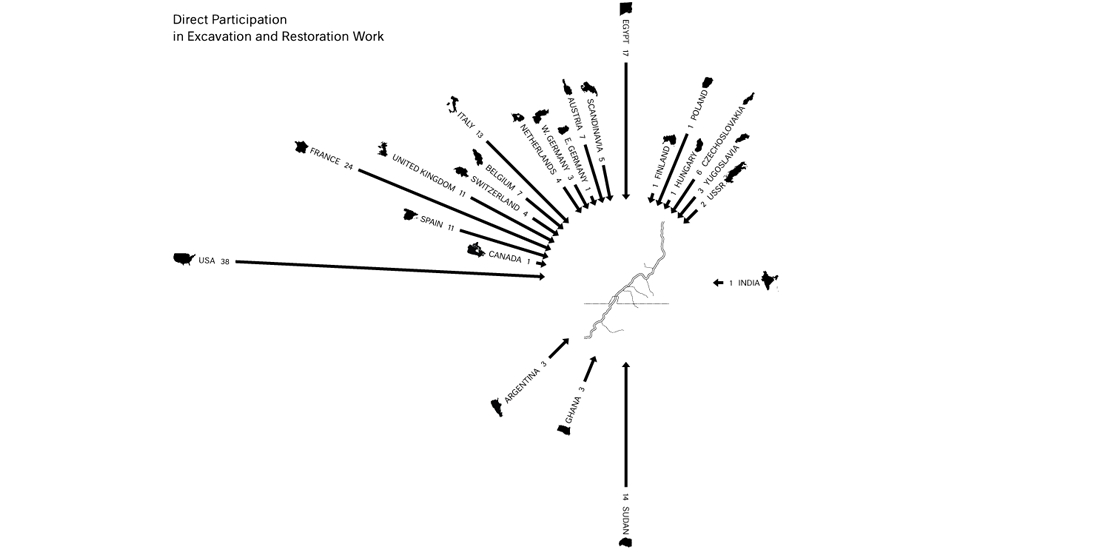

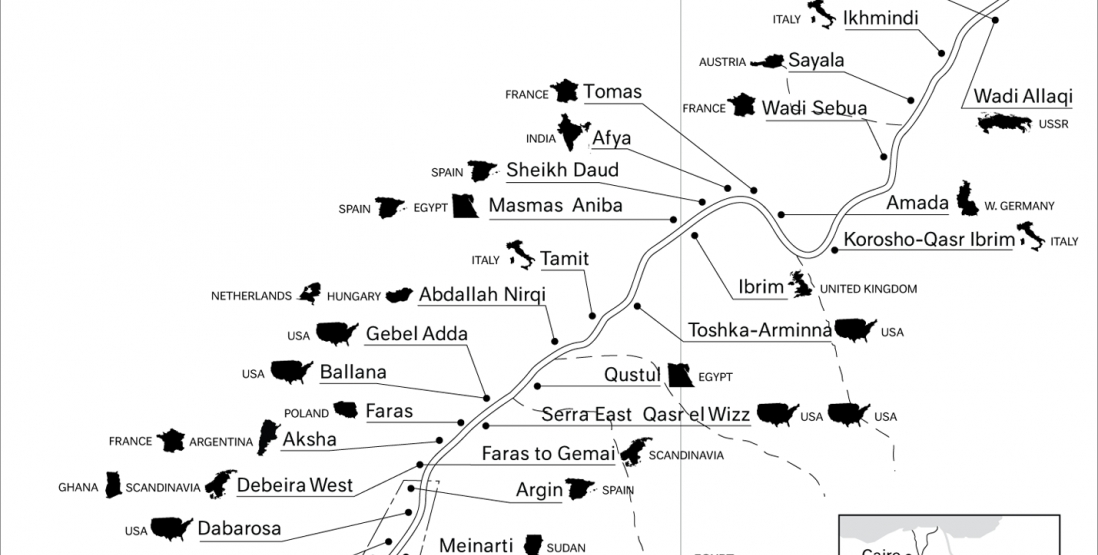

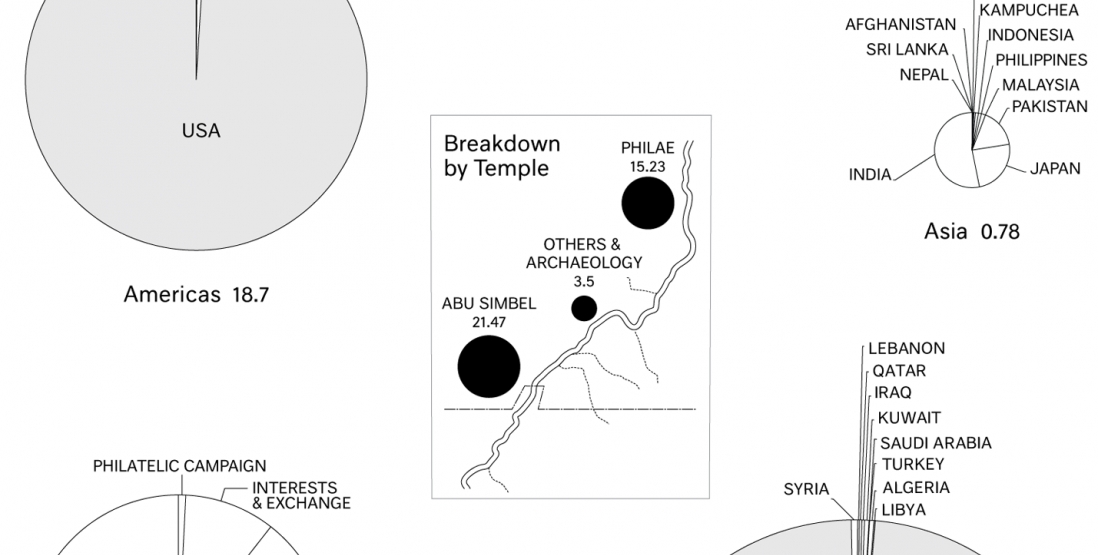

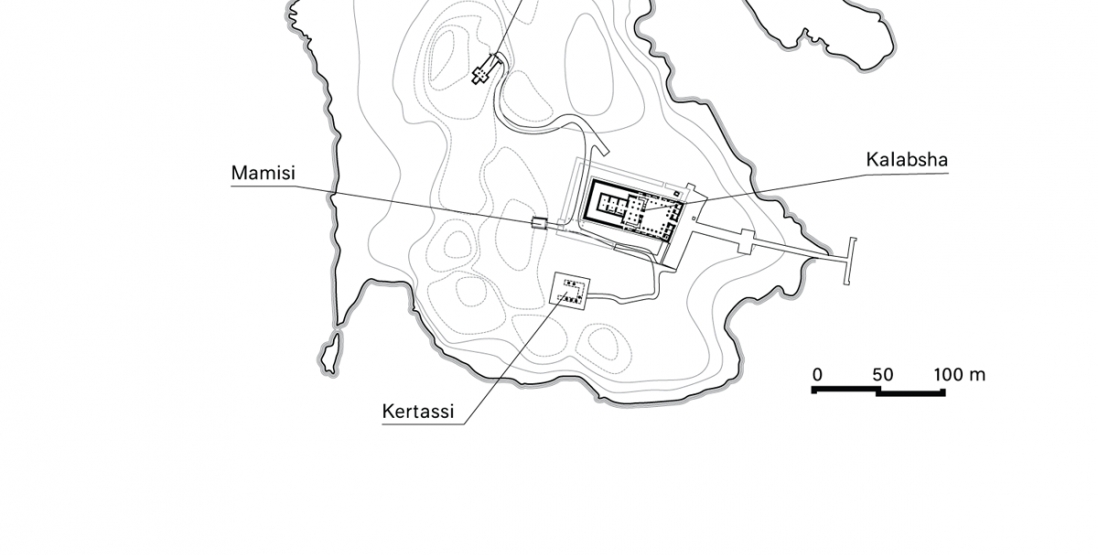

Consider the following architectural event: between 1960 and 1980 twenty-four Egyptian temples were surveyed, dismantled, and relocated from their original sites on the banks of the Nile to make way for an enormous reservoir lake created by the building of the Aswan High Dam. Designed to render fertile entire stretches of desert and bring electricity downstream to Cairo, the dam was also scheduled to flood the entire region of Nubia, a long and narrow strip that crosses the border between Egypt and the Sudan, sparsely dotted with mud-brick villages, archaeological sites, and Pharaonic temples. Two groups of temples (the island of Philae and the monoliths of Abu Simbel) were moved by a few hundred yards to nearly identical sites. Eleven others (such as the temple of Amada) were rebuilt and grouped in three oases overlooking the new Lake Nasser. Seven more temples (including the fortress of Buhen) were placed in national museums in Aswan and Khartoum. The last five (including the temple of Dendur, now at the Metropolitan Museum in New York) were sent to Western museums as “grants-in-return” for technical and financial assistance. Fifty nation-states took part in these operations, sending more than 150 teams of experts to Nubia and contributing a total of forty million dollars to a trust fund managed by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).1

—Lucia Allais

✓ Not peer-reviewed

Lucia Allais, “The Design of the Nubian Desert,” Aggregate 2 (September 2014), https://doi.org/10.53965/CXYS3095.

- 1

Opening paragraph of Lucia Allais, “The Design of the Nubian Desert: Monuments, Mobility, and the Space of Global Culture,” in Governing by Design: Architecture, Economy, and Politics in the Twentieth Century, ed. The Aggregate Architectural History Collaborative (Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, 2012), 179.

↑