Just-So Stories in Real Estate History, or, How the Apartment Tower Got Its Glass Skin

How the Apartment Tower Got Its Glass Skin.

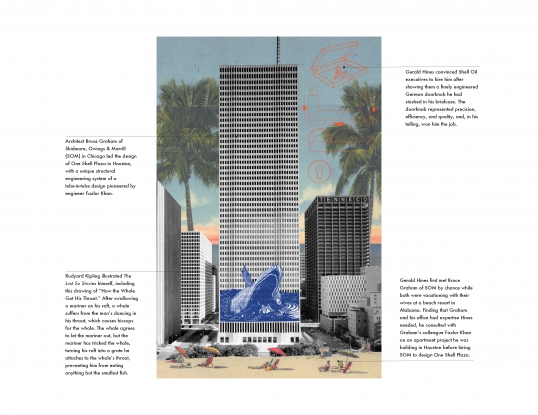

Collage by the author.Architects’ clients are often real estate developers, and their access to capital brokers the transformation of money and drawings into bricks and steel. Stories about these developers pepper the history of architecture. In retelling their professional narratives, they repeat self-serving, vignette-style stories of their success to the pleasure of their interviewers, looking to secure their legacy or package their professional identity into calling cards for soliciting further business. Printed in business publications and collected into tomes like Zeckendorf: The Autobiography of William Zeckendorf, They Built Chicago, The Land Lords, Hines: A Legacy of Quality, Trump: The Art of the Deal, Trammell Crow: A Legacy of Real Estate Business Innovation, and Risk, Ruin & Riches, to name a few, these narratives often constitute the bulk of the historical record.1 Real estate developers have rarely left archives of their deal-making activities, so historians are left to fill in the picture of how they operated by looking through affiliates’ materials with a critical eye and gleaning what they can of the profession’s tendencies and contributions to the making of the built environment. These stories told by the developers become grist for the historians’ mill, and yet the structure of the stories themselves, their genre, is rarely investigated.

Real estate history often centers on not just facts and figures but also personalities and professional networks filled with self-made characters that seem to come from fables. But what happens when real estate history’s narrative threads are pulled loose from the warp and weft of the mythologies of the cultivated professional personality? By exploring how the technical operations of financial markets function in an environment colored by personalities and social practices, we can see architecture from a perspective that accounts for the fictions of finance. This article will use three narratives about real estate developers to explain how these stories are operative, both as makers of meaning and as obfuscators of other forms of agency, in shaping our reading of the past.2 These narratives, from the history of architecture and development in the midcentury United States, will begin this analysis, which I will relate to Rudyard Kipling’s “just so” stories:

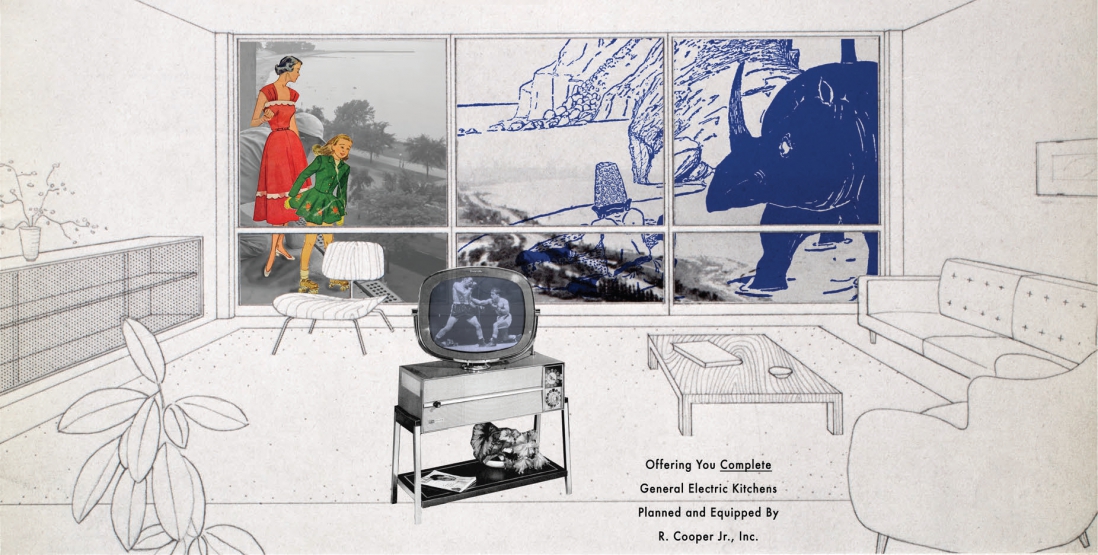

How the Apartment Tower Got Its Glass Skin. Collage by the author. Includes a rendering of Promontory/Algonquin Apartments, Office of Mies van der Rohe, Art Institute of Chicago; and Rudyard Kipling illustration, “How the Rhinoceros Got His Skin,” from Rudyard Kipling, Just So Stories for Little Children (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1925), 29. On the boxing story, see Edward A. Duckett, Joseph Y. Fujikawa, and William S. Shell, Impressions of Mies: An Interview on Mies van der Rohe; His Early Chicago Years 1938–1958 (Chicago: n.p., 1988), 30.

How the Apartment Tower Got Its Glass Skin. After immigrating to the United States and settling in Chicago at the Illinois Institute of Technology, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe found his best client in a young and inexperienced developer, Herbert Greenwald. Between 1946 and 1949, they built an apartment tower, Promontory Apartments, through mutual-ownership cooperative financing, as banks would not give them any loans. After that first project’s success, they returned to banks and other investors to finance a second tower. This project, called the Algonquin, was set to be the first curtain-wall apartment tower in Chicago. In their quest for financing, Greenwald approached Clifford McElvain, a financier with the Western & Southern Life Assurance Company, who expressed hesitant interest in the project but also concern about its stark modernism and, in particular, the floor-to-ceiling glass proposed for inside the apartments. Before approving financing, McElvain performed a test: he took his wife and daughter to a hotel penthouse bar that had floor-to-ceiling glass. Afraid that buyers would not want to live next to vertigo-inducing floor-to-ceiling glass, he observed his female test subjects’ comfort level when seated at the curtain wall. Only when he saw, through a veil of paternalism and misogyny, that the womenfolk were perfectly relaxed did he approve the loan. While the Algonquin was ultimately not built with the floor-to-ceiling glass indicated in the original scheme, McElvain’s approval enabled the financing of Mies’ most famous apartment towers, at 860–880 Lake Shore Drive, with their dramatically modernist glass-and-steel façades.3

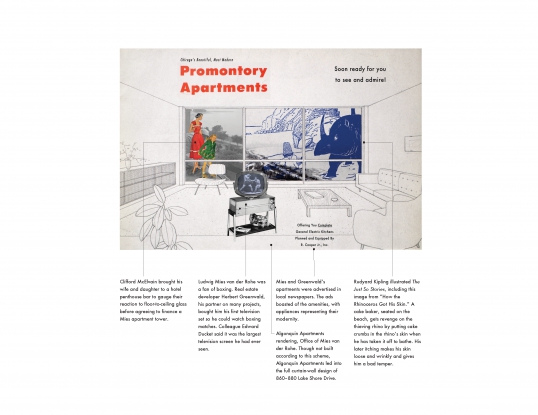

How a Fringed Vest Earned Denver’s Trust. Collage by the author. Quote from William Zeckendorf and Edward A. McCreary, Zeckendorf: The Autobiography of William Zeckendorf (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970), 136. Includes an advertisement for the Denver Hilton Hotel and the adjacent May D&F department store, developed by William Zeckendorf and executed by I. M. Pei’s team (Conrad N. Hilton College Archives and Library, University of Houston); and a Kipling illustration, “The Elephant’s Child,” from Rudyard Kipling, Just So Stories for Little Children (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1925), 73.

How a Fringed Vest Earned Denver’s Trust. Real estate developer William Zeckendorf earned fame for securing the site for the United Nations headquarters in New York City. He then launched the career of Ieoh Ming Pei from inside the architectural division of his office at Webb & Knapp. Zeckendorf was the most prolific of the few developers in the country who aggressively courted urban renewal projects under Title I policies of the Housing Act of 1949 (rev. 1956), commencing thirty studies, offering up fifteen proposals, and building eight urban renewal projects.4 Before Title I, when he first switched from financing and investing to developing new sites and building on them, Zeckendorf built his first major projects in Denver, including an office tower, a department store, and a Hilton hotel, but after he bought the sites it took years to get the backing needed to build. The local business elites simply shut out a brash Jew from the East Coast; he was an outsider, with outsider money, chasing after profits in their city. But the gregarious Zeckendorf secured an invitation to the Denver Post’s annual Frontier Days celebration in Cheyenne, Wyoming. At the event, Zeckendorf proved his western bona fides, showing up in a cowboy costume complete with his own grandfather’s Colt .45 in his holster. His colorful participation in the ritual gained him acceptance from the business community. After this event and the social connections it garnered, his projects moved ahead without delay.5

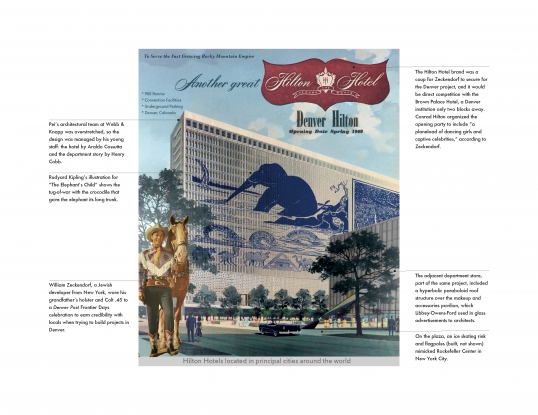

How a Doorknob Delivered a Skyscraper. Collage by the author. Includes 1971 photograph of One Shell Plaza by SOM and Gerald Hines; and a Rudyard Kipling illustration, “How the Whale Got His Throat,” from Rudyard Kipling, Just So Stories for Little Children (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1925), 5.

How a Doorknob Delivered a Skyscraper. Gerald Hines founded what is today a global real estate company known for working with renowned architects on large, signature projects in major cities around the world. In 1966, Gerald Hines was a young real estate developer in Houston who had built about a dozen speculative small suburban office buildings. He wanted to break into the downtown office tower market but struggled to make the jump in scale, failing to win a bid for a gas company tower. When Shell Oil began looking for a developer to build a new regional headquarters downtown, Hines contacted SOM architect Bruce Graham, whom he had met at a beach resort. Graham had the experience Hines lacked in designing towers. With little preparation, Hines and Graham met with Shell executives. Without a design proposal from Graham and without a portfolio of completed towers from Hines, they faced long odds. Graham later recalled Hines’ presentation: when Shell asked Graham what the building would look like, Hines stepped up to the table with his briefcase and opened it. Inside was a set of finely crafted German door hardware, and Hines stated that the building would be as precisely engineered, with as high quality a design as those doorknobs. He won the project, later leveraging this success to gain subsequent projects.6

Kipling’s Template

Rudyard Kipling published Just So Stories for Little Children in 1902, based on bedtime tales he wove for his children.7 Reviews of Just So Stories from around the time of its publication describe how the tales are partly intended for children and partly for adult audiences.8 The stories themselves—how the camel got its hump, how the leopard got its spots, how the whale got its throat—are mock-evolutionary tales that naturalize the outstanding anatomy of exotic, anthropomorphized animals. Lamarckian (or now we might say epigenetic) in their orientation, Kipling’s evolutions present how acquired traits cause change in a species rather than the slow Darwinian process of natural selection.9

The first edition of Kipling’s book included his own illustrations. They were compelling if amateurish drawings, some with decorative borders and an undercurrent of exoticism reminiscent of art nouveau.10 The wide areas of black set against white backgrounds bear similarities to Japanese wood block prints or Aubrey Beardsley illustrations, with bold if sometimes awkward compositions and clumsy figures. His visual skills come with a familial association: Kipling’s father was a professor of architectural sculpture in Bombay (he trained many of the artists responsible for the relief work on the Victoria Terminus railway building by architect Frederick William Stevens) and occasional illustrator of his son’s books, contributing drawings to The Jungle Book (1894) and Kim (1901).11 Although the illustrations in Kipling’s books often engaged the relationship between the visual and the text, Kipling himself illustrated only the Just So Stories.

The simplicity and vividness of the tales will appeal to any audience; absent is any specialized knowledge or jargon, and in their place are playful, made-up words (the “ooshy-skooshy” ocean, the “sticky-up masts” of ships, the “spickly-speckly forest,” and the “splotchy-blotchy tree”). The words and drawings suggest the low stakes of childhood playfulness. Without any overwhelming didacticism, they are not parables but fanciful tales not intended to be instructive or to model good behavior. They are explanatory, simple, vivid, naturalizing, and entertaining as they describe a transformation. They make scientific categorization and evolution into narratives, replacing reality (or scientific knowledge) with fanciful, formalist invention.

The tales are also a window into Kipling’s advancement of colonialism and racial privilege and are thus difficult to read today. To wit, one tale uses a racist epithet beginning with the letter n as an Ethiopian paints himself black with an inky finger before dotting spots on the leopard, and orientalist tropes run throughout the stories. Kipling’s childhood experiences of British colonialism and his family connection to art, drawing, and nation-building in the Indian context surely shaped his ideas about race. Such a childhood allowed him to form a worldview in which the god-like behavior of shaping a species’ form is based on the invention of race as if it were a biological fact, one seen to be as scientific as understanding a leopard’s spots. A few years prior, Kipling had published a poem, “A White Man’s Burden: The United States and the Philippine Islands” (1899), to persuade the United States to colonize Filipino lands following the Spanish-American War, thereby collapsing Eurocentrism, racism, and colonialism under the cover of virtuous condescension and patriarchy.12 Lest that association still seem too tame, the white supremacist Thomas Dixon Jr., author of the novel that was made into the film Birth of a Nation, would repurpose the title of one Kipling tale and combine it with Kipling’s poem into a Ku Klux Klan–glorifying novel, The Leopard’s Spots: A Romance of the White Man’s Burden, 1865–1900 (1902). The just-so stories are inseparable from these painful racist and colonialist histories; indeed, they form part of the cultural foundations of structural racism. They also demonstrate a format through which the levers of power can be hidden, like a sleight of hand.

Why use these racist tales as a lens to study real estate history? Like the just-so stories, the real estate tales are told without reference to any particular moral compass, they do not press the reader to measure right versus wrong, nor do they offer a set of instructions that the reader could repeat or use as a road map or how-to guide. One cannot read any of the Kipling stories and know how to give another animal spots, nor does one know how to land a big project after reading the developers’ stories. They are often about the productive nature of the fluke.13 Something happens, that is, a fluke (e.g., Hines meets Bruce Graham on the beach in Alabama, a financier gauges risk according to the reactions of his wife and daughter), and a spark of expertise makes that accident productive. The fluke offers a point of leverage whereby the developer cleverly finds a way to overcome some hurdle. Both types of stories, from Kipling and from developers, artfully cover over the mechanisms of power. The manipulative capitalist obscures his profit motives, hides his trade secrets, sidesteps blame, and naturalizes the process under the rubric of luck, of happy accidents. Just as the Kipling stories rely on a foundation of colonialism and racism, the developers’ stories rely on a culture of masculinity and misogyny: the briefcase, the Colt .45, the easily flustered womenfolk.14 The gendering of behavior, gestures, and objects in the stories signals an assumption of masculinity that establishes the culture of real estate development. The accident is triggered only when the conditions of gender are met. (See “Postscript” below on connections to Donald Trump.)

With a fluke as its sole organizing device, the just-so story in real estate offers at least three layers of meaning. There is the story itself (a thing that talks), the meaning it gives to the developer’s professional personality (it conjures), and the inapplicability it acquires relative to the larger world (it is unrepeatable). In the Hines story, the door handle is the talking object, a technology that represents a way of thinking about a building. The conjuring happens with the opening of the briefcase, as Hines’ showmanship (safely within the metes and bounds of business culture) dazzles his audience, and the inapplicability occurs when the board hires Hines. The overall picture is one of the magnetic personality of an individual—the right person for the job, the right moment—unlocking a secret passageway to success (and in the meantime obscuring the structural conditions of capitalism and the avenues of white male privilege open to its protagonists). The story is retold not to explain Hines’ genius, I argue, but to display his masterful negotiation of social capital, his insight into the mind of the client. Opacity is the real intention: to mystify and intrigue, not to draw a road map for others to follow.15 To illustrate mastery without revealing the magic tricks.

The cleverness is key, because these stories are never about dogged perseverance in the face of adversity but about finding an inspiration—one born of experience and combined with a willingness to take calculated risks—that proves fruitful. Zeckendorf arrives in a fringed vest with a revolver at his hip for the Denver Post party because, though the action is risky, the possible benefit (acceptance into the elite community) is worth the gamble. This type of story exists outside the professional project of real estate developers, aiming at a different object: to establish uniqueness and to personalize experience and expertise for the individual practitioner. Nonetheless, when collected together, they can be read as mock-evolutionary tales of real estate developers who have transformed themselves from curbstoners to respected professionals, from college dropouts to real estate magnates.

These stories that surround expertise serve as currency in the cultural economy of real estate development. They are relevant because they show three things about the nature of expertise: (1) the importance of focusing on the scale of the individual, (2) the way expertise hides capitalism’s structural conditions, and (3) the way it relies on individuals’ social networks and social skills to prove the value of their knowledge. It is not just impersonal bureaucratic systems that rule the real estate world, not just the calculations of appraisers and loan officers, but the face-to-face meetings of egos and personalities.

While architectural history certainly includes grandiose stories about individual practitioners with larger-than-life biographies, many historians recognize and highlight the social side of establishing a legitimate architectural practice. Here, architectural history appears closest to the history of real estate development, that is, as a business history constrained by the need for positive public perception. Mary N. Woods’ analysis of Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s view of the professional architect as a balance between theory (artistic endeavor) and practice (building construction) posits that the hard-won compromises in his career ultimately associated the professional architect with high-profile state commissions and public buildings. Sibel Bozdogan Dostoglu’s study of Chicago in the late nineteenth century describes the tension between architecture-as-business and architecture-as-art as being detrimental to architects’ attempts to earn the full credential of “professional.”16 Both of these arguments present the technical and artistic realms as significant and as representing legitimate avenues to professional status, and both professions checked off similar boxes on the way to professional status (i.e., having national organizations, codes of ethics, etc.), but for real estate developers, the path to professionalization was much less clear. How might wheeling-and-dealing translate into a licensing exam? How did the soft skills of matchmaking land, program, and capital come to be seen as legitimate? The just-so story renders visible aspects of this process and offers a unique perspective on the social practices of the field. Architectural historians have addressed this process in many contexts, of course, from the patronage of King Henry IV in Paris to Daniel Burnham’s work in Chicago, underscoring the social dimensions of architectural success.17 Studying these real estate stories, then, adds another angle to our understanding of how social practices also shaped the profession of architecture.

Bootstrap Stories

The question of morality appears differently in these just-so stories than it would in the trade journal of a professionalizing field. Real estate brokers from decades past would have sought to establish themselves as moral actors working to serve both the public’s and their own interests. By raising the public’s perception of their field, real estate brokers collectively increased trust in it and promoted greater stability in the marketplace (often by lobbying for legal protections for the field as a whole).18 To address the question of moral marketplace behavior in the construction of real estate expertise requires another type of story.

At a scale somewhere between the professionalization story and the just-so story is the rags-to-riches biography. Horatio Alger’s novels portray noble, moral young men whose singular efforts lift them out of poverty and propel them into the respectable middle class. His characters are set apart from the crowd, independent, and hard working. Industriousness and clean living result in upward mobility and success. Developers’ own life stories are often retold in this framework, and they begin their career trajectories without formal training (there were no degree programs in real estate until 1967).19 They pursue work through lean years, struggling with adversity to find financing before eventually achieving success and building large-scale projects. Alger’s stories, which he began publishing in the 1860s, had fallen into obscurity by the gilded 1890s but then experienced a resurgence of popularity in the first decades of the twentieth century, thus paralleling the publication and popularity of Kipling’s Just So Stories.20

The professionalization of real estate developers followed the same timeline. After early efforts to organize the real estate industry into local real estate boards in the mid-nineteenth century, the organizational process at the national level stalled out quickly. A second wave of interest in elevating the professional status of the field gathered strength in the early years of the twentieth century, with the founding of the National Association of Real Estate Exchanges in 1908 (now known as the National Association of Realtors).21 Alger and Kipling produced a set of ideas and narratives that shaped the coming generations of real estate developers, who were eager to narrate their own success stories and slyly present their working methods.

Kansas City developer J. C. Nichols is one real estate developer who reflects the scenario presented in Alger’s stories. Nichols is best known for having developed one of the first shopping centers, and he spent decades developing a large residential district governed by a strong set of deed restrictions. He was also a significant figure in the professionalization of real estate developers, having been involved in the early years of the National Association of Real Estate Boards. Nichols was also one of the founders of the Urban Land Institute, known today as the primary nonprofit organization promoting best practices in global real estate development. Presenting himself as ever the simple farm boy (never mind that semester at Harvard studying economics), Nichols not only modeled an Alger hero in describing his youth but later became the wealthy benefactor who nurtured young up-and-comers in the field, with a cast of former protégés speaking at his funeral (Houston’s Hugh Potter, for example).

Other developers presented their background-as-qualifications rather differently. Herbert Greenwald, the young Chicago developer who worked with Mies van der Rohe, improved his own reputation through two cultural connections that distanced him from the morally base world of capital production; Stanley Tigerman (among others) remembers him as an “ex-rabbinical student” burnishing his monastic cultural capital.22 Then, as an early student in the Great Books program at the University of Chicago, Greenwald’s philosophy studies enhanced his cultural capital, diluted the strength of his Jewish heritage, and suppressed his education at Yeshiva University.23 Just as when the industrious Horatio Alger character meets the wealthy benefactor through a fluke, the young developers (in something of a sleight of hand) found success through unrepeatable circumstances but were able to leverage those circumstances because of skills acquired from work experience.24 They crafted their life stories into tales of perseverance and self-reliance as if social networking and privilege played no part.

The typical Alger story arose from a culture lashed by a boom-and-bust economy that produced winners and losers without reliance on the ethics and social mores of days gone by. The antimorality plays performed in newspaper headlines by Wall Street tycoons troubled public perceptions of success. Jonathan Levy argues in his book Freaks of Fortune that American culture struggled to accept changing ideas about risk and reward in the late nineteenth century. In a boom-and-bust economy Americans were unaccustomed to the idea that risk deserved financial reward, and Wall Street success stories became “the anti–Horatio Alger plotline.”25 Developers managed to find a third way, relying on the same calculations of risk-for-reward as Wall Street tycoons yet crafting their biographies to match the Horatio Alger tale without a wink of irony. (Developers did, after all, lobby for regulatory protections of their trade, and they actively participated in debates on city planning and zoning. Their collective professionalizing project was not antiregulation, and certainly they all relied on social networks to find their success.26) Like the Alger tale, the self-made developer biography, Janus-faced though it was, paved the way toward a laissez-faire interpretation of the economy that focused on self-reliance and independence from government involvement or regulation, thereby producing success.

Following not just the money but also the social capital in real estate development leads us to something other than an expected history of real estate. Instead of focusing on the history of appraisal techniques, mortgage financing, the legal history of deeds and covenants, and fiscal policy, the cultural dimension takes precedence. Instead of performing a large-scale accounting of real estate markets, as the historian Carl Condit has done, or aligning with Homer Hoyt’s land economics, a culturally focused study of the profession probes the practices of real estate developers in order to address the cultivation of expertise.27 This focus allows historians to capture the features and context of the typical real estate deal and to explain the most successful developers’ rise to power.

Conjuring the Fictions of Finance

Paying attention to real estate developers’ own formulations of their expertise—as a genre or typological study—shifts the emphasis from a study about markets to one on professionalization. The cultivation of expertise by real estate developers was key to their professionalization, and it explains some of the field’s path to professionalization. To understand how developers put these stories to use requires thinking through the meaning of expertise, both historically and in this context. Expertise can be seen as not just an indicator for the ability to raise capital but as a guard against uncertainty (which is different from risk in that it is unmeasurable and unpredictable). In the literature known as studies of expertise and experience (SEE), the type of expertise, or tacit knowledge, relevant here is interactional expertise, which indicates a fluency in the specialized language of a particular area of activity and marks a social transition into the cast of experts without denoting competency.28 The interactional expertise of developers shows that knowledge of policy, financing, and planning procedures in, say, Denver is not too far removed from a similar project type in Duluth or Dubai (a similarity underscored by comparable financing procedures and more global financing organizations). But at the finer grain represented in these developer-narrated stories, the actions that develop acumen do not scale up easily into an industry-wide narrative. The smaller-scale stories investigate a different register, one that helps to acknowledge the texture of the real estate deal. I have framed these vignettes from real estate history as just-so stories to show that expertise became both operative and fanciful in everyday negotiations and that architectural history and real estate history are narratively intertwined.

If we can digest how developers came to acquire and deploy expertise, how then do we as historians process and mine these stories for meaning? Put another way, how can we understand their representational capacities? For historians of science, microstudies of objects, such as those on bicycle wheels, personal rapid transit, air pumps, and refrigerators (think of Lorraine Daston’s Things That Talk) are doubly representative.29 They represent technoscientific activity as well as the specific context, historical and geographic, of that moment. As such, Ken Alder has characterized object stories as having a “double representativeness [that] endows these tales with an incantatory quality, as if they could conjure up an entire moral economy around the fate of a single thing.”30 Likewise, stories about real estate development show not only context but the fiscal, technical, and policy activity that circles around a deal. And they are designed to conjure, to invoke an unattainable, un-copy-able expertise (a salescraft), which means their analysis requires a critical reading of the story to discern intent and strategy.

These stories can mislead in two ways. First, they mislead through overdetermination, whereby the story suggests multiple causes for success (for example, experience, social connection, luck) when only one would have produced that success. Second, the autobiographical story can mislead through enhanced oversimplification, in which the story suggests a too-easy, pat solution to a complex problem.31 Popular press descriptions of financial markets dwell in particular on the abstract character of the field; the same abstractions surrounding market relations spur many individuals to build narratives. Leigh Claire La Berge studies how scholarly discourse struggles with this condition: the financial press vacillates between two refrains—that markets are “abstract” and/or “complex.”32 The anthropologist Caitlin Zaloom observes how today’s stock traders (open-outcry pit traders) enhance their skills by “storifying” their experiences to narrate the movements of the market.33 In other words, narrative construction is a component of decision-making that is not simply about projecting an image, as it is also geared toward constructing (and then reinforcing) expertise through narrative. In other words, overdetermination and oversimplification are narrative techniques that can help to tell stories about finance, make sense of it, and obfuscate.

Many sales fields, whether in finance or real estate or some other business sector, have also employed narrative to construct personality. In the early decades of the twentieth century, American advertisers discussed how best to apply narrative as an advertising technique, as T. J. Jackson Lears has shown.34 For these advertisers, stories could establish a personality for the product on offer, inanimate though it might be, and they used this language to discuss best practices in trade journals in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One adman, himself both a copywriter and published short-story author, argues in the advertisers’ journal Printers’ Ink in 1915 that Rudyard Kipling understood “the singular closeness of the kinship between the story-writer and the copywriter.”35 In advocating for advertisers to adopt storytelling methods in their copy, the adman suggests that writers like Kipling (along with Hawthorne, Poe, and O. Henry) have shown how “brevity, vividness, atmosphere, and attention-grabbing narrative” have a powerful impact on readers and that ad writers should style their copy using the same techniques.36 In building up a narrative around a product (unrelated to its manufacturing, technical details, or performance measures), advertisers created personalities for products, and consumers responded to them. According to Lears, the stories used by advertisers often involved “conventional tales of the manufacturer’s rise from penniless to powerful.”37 (Horatio Alger stories sold well, in other words.) Similarly, door-to-door sellers applied narrative to entertain and bemuse potential customers, building their own sales skills in the process, as Walter Friedman’s history of sales reps (and modern sales management) describes.38 While real estate developers are not alone in wanting to communicate through narrative, they built on a longer history of relating narrative and sales expertise to communicate value.

How the Napkin Cut the Tower in Two. In 1971, the real estate developer Gerald Hines sought another tower project in downtown Houston, this one for Pennzoil. The high land value demanded maximizing the building’s size, but Pennzoil needed only about half that space. So Hines had to find a secondary tenant and pitch them on a shared tower. In Houston’s oil-dominated economy, that tenant was likely to be a competitor to Pennzoil, making a shared building a very difficult sell. Hines approached architect Philip Johnson on a plane ride and explained his dilemma. Johnson proposed—in a napkin sketch drawn on the armrest of his plane seat—a double-tower scheme consisting of two trapezoids. The scheme separated the two tenants into their own towers, bisecting the space to maintain an aura of independence for each company. Johnson’s proposal, far from the most efficient solution (given the doubled cores), solved the question of how to market a square downtown site to two tenants. With the split space and Johnson’s iconic design, Hines was able to prelease the second tower to Zapata Oil and Arthur Andersen, pleasing all clients.39

The shorthand language of architectural design is the napkin sketch. Through it, architects communicate their value to clients as both practical problem solvers and as gifted artists. The napkin sketch contains the germ of an idea, alighted on by the sheer talent of the architect’s hand. The too-absorbent paper and short strokes of bleeding ink convey the designer’s inspiration in answer to the client’s needs. In the just-so real estate story, a spark of inspiration always hits the protagonist to motivate the narrative, and if that protagonist is the architect, then it often appears inked on a cocktail napkin. Napkin sketches do so much: they conjure, they talk. They are sold at auction, commissioned for fundraisers, filed away in archives, collected in books, and sentimentally resurrected in competitions.40 Alvar Aalto, himself a practitioner of the napkin sketch, famously said, “God made paper to draw architecture on it,” but surely architecture’s bill of sale came on a cocktail napkin, with a flourish.41 As a representation of architectural expertise, the napkin sketch performs on the spot, with whatever materials are at hand. Different from the parti or the esquisse, the napkin sketch is not a holdover from the Beaux Arts; rather, it follows a direct line from the gritty world of business and construction, representing real-world, practical skills overlaid with artistic talent and training.42 The napkin sketch resolves.

Through the napkin sketch, the problem of the developer becomes the asset of the design, and the project evolves from a pro forma into an image with the power to win over architectural critics. For the developer, the napkin sketch is the evolutionary vehicle, and in it market relations become visible and expertise becomes operative and theatrical. With the just-so stories, the bootstrap stories, and the napkin sketches, new kinds of expertise are enacted, to be recast later in tales whose utilization hides the rough edges of economic transactions. The narratives that historicize financial transaction are colonial, naturalized, and based on affect. Archival work by scholars holds the potential to provide other narratives and also to recognize and analyze these recurring tropes to understand their histories as racist and colonialist, to see how they operate to legitimize and narrate a market. Without unpacking these stories and forms of expertise, our understanding of the process of change in the built environment would fall short. Rather, in interpreting and contextualizing the stories that real estate developers tell, historians can find new depths in the connections between narrative forms and capitalist relations that drive richer understandings of the built environment.

Postscript

The first chapter of Trump: The Art of the Deal follows a typical week for Donald Trump circa 1987. It is packed with phone calls to important people and sidebar comments about how unimportant lunch is, and it serves to communicate his connectedness to the deepest pockets and most powerful elites. Not far into the chapter, he notes that a fellow real estate developer, Abraham Hirschfeld, who calls Trump for advice, makes a better real estate developer than he does a politician. Hirschfeld would later that year launch Trump’s first campaign for president.43 Tracing the line from this first book to his later political ambitions underscores how important story-making has been in inventing his persona, as well as how much the political moment of neoliberalism and deregulation shaped his ideology.

Trump: The Art of the Deal fits clearly into the genre of autobiographies of real estate developers that outline their early days and entry into bigger and bigger projects, putting on the airs of a faux Horatio Alger story, showcasing the self-made mogul who knows everyone in town, living out the personality required of their trade, or what I refer to as the practice of “salescraft.” (Trump even referred to his real estate developer father’s story as “classic Horatio Alger,” though his own is more of the silver-spoon variety.44)

The rise of Trump’s political profile suggests that the prominence of real estate development in American culture is higher than ever before. His identity as a real estate developer, established through his book and maintained for decades, aligns with cultural touchstones that established real estate and Wall Street as hotbeds of a particular type of American capitalism.45 The same time period marks the ascendance of neoliberal capitalism.46 Trump made meaning through narrative, playing off cultural tropes while sidestepping any explanation of the simultaneous structural shifts in the economy.

Trump’s early career, as outlined in his autobiography, shaped his views of the public, of government, of financial regulation, and of the role of the press. In moving projects forward, Trump often dealt with communities but saw them only as roadblocks to his projects, never as opportunities to make better places for people. Trump roundly complains about the lack of tax breaks that city governments offered his projects, about the lack of increased densities he requested, and about any planning controls that presented limits to his projects; in his telling, government was an obstacle. Similarly, financial regulations shut down opportunities to attract investors or held back potential incentives to different sources of financing, all of which he saw as yet another hurdle he had to get around. And finally, his manipulation of the press was a tool for manufacturing publicity, a tactic that he had used often by the time Trump: The Art of the Deal came out: “If there’s one thing I’ve learned from dealing with politicians over the years, it’s that the only thing guaranteed to force them into action is the press—or, more specifically, fear of the press. You can apply all kinds of pressure, make all sorts of pleas and threats, contribute large sums of money to their campaigns, and generally it gets you nothing. But raise the possibility of bad press, even in an obscure publication, and most politicians will jump.”47

Throughout the book, his ability to craft narratives and stories from his experiences serves to illustrate the arrival of this shaman of neoliberal capitalism. Real estate development trades in the most abstract of commodities: the deed, a piece of paper signifying a spot of land, and the right to put something else on that land.48 It models a form of neoliberal governance whereby business acumen and an ability to govern are one and the same, a form in which the private sector would do well running the public sector. Trump thus represents an endgame of neoliberal politics, an era of financialization that collapses political-economic complexities into digestible narratives, cloaking violence and evil in neat stories that end, just-so, or at least, just-so-enough until the noise of the next distracting story begins. With Trump, the just-so story has been fully weaponized.

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Sara Stevens, “Just-So Stories in Real Estate History, or, How the Apartment Tower Got Its Glass Skin,” Aggregate 7 (September 2019), https://doi.org/10.53965/XSAX5254.

- 1

William Zeckendorf and Edward A. McCreary, Zeckendorf: The Autobiography of William Zeckendorf (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1970); Miles L. Berger, They Built Chicago: Entrepreneurs Who Shaped a Great City’s Architecture (Chicago: Bonus Books, 1992); Eugene Rachlis, The Land Lords (New York: Random House, 1963); Mark Seal, Hines: A Legacy of Quality in the Built Environment (Bainbridge Island, WA: Fenwick, 2007); Donald Trump, Trump: The Art of the Deal (New York: Random House, 1987); William Bragg Ewald, Trammell Crow: A Legacy of Real Estate Business Innovation (Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 2005); Jim Powell, Risk, Ruin & Riches: Inside the World of Big Time Real Estate (New York: Macmillan, 1986).

↑ - 2

Reinhold Martin explores the character of the real estate developer in an essay about Donald Trump’s presidency. See Reinhold Martin, “The Demagogue Takes the Stage,” Places Journal, 28 March 2017.

↑ - 3

Betty J. Blum, “Interview with Charles Booth Genther,” 1995, 23–24, Chicago Architects Oral History Project, Department of Architecture, Art Institute of Chicago. This story is recounted in more detail in Sara Stevens, Developing Expertise: Architecture and Real Estate in Metropolitan America (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 155–56.

↑ - 4

Zeckendorf and McCreary, Zeckendorf, 226–27; Hilary Ballon, “Robert Moses and Urban Renewal: The Title I Program,” in Robert Moses and the Modern City: The Transformation of New York, ed. Hilary Ballon and Kenneth Jackson (New York: Norton, 2007), 102.

↑ - 5

Stevens, Developing Expertise, 206; Zeckendorf and McCreary, Zeckendorf, 129–30.

↑ - 6

Seal, Hines, 25–27; Sara Stevens, “Hines in Houston: The Urbanism of Architectural Exceptionalism” (presentation at the Society of Architectural Historians Annual Conference, Austin, TX, 9–13 April 2014); Sara Stevens, “Speculative,” ARPA Journal: Applied Research Practices in Architecture, “Conflicts of Interest” issue, no. 05, 24 May 2018.

↑ - 7

Rudyard Kipling, Just So Stories for Little Children (1902; Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1925).

↑ - 8

Bertha Payne, review of Just So Stories for Little Children, by Rudyard Kipling, Elementary School Teacher 3, no. 5 (1903): 330–31.

↑ - 9

The biologist and science writer Stephen Jay Gould caused a resurgence of interest in the Just So Stories in 1978, when he used them to characterize a trend he saw in sociobiology. Stephen Jay Gould, “Sociobiology: The Art of Storytelling,” New Scientist, 16 November 1978, 530–33. Following Gould’s perhaps enthusiastic or even cavalier use, the term “just-so story” has since functioned as an insult when directed toward hypotheses about evolution. New ideas about evolutionary development are immediately labeled as false, even fanciful, when a scientist appends “‘just-so” to an idea. As Glen Love notes, the “biologist John Alcock, in The Triumph of Sociobiology, calls the just-so epithet ‘one of the most successful derogatory labels ever invented, having entered common parlance as a name for any explanation about behavior, especially human behavior, that someone wishes to dispute.’” Glen A. Love, Practical Ecocriticism: Literature, Biology, and the Environment (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2003), 71. For a discussion of the term “just so” in evolutionary science and the blank slate theory of human behavior, see Love, Practical Ecocriticism, 70–72. Recent scholarship in biology on the Kiplingesque topic of how the leopard got its spots has indeed quoted Kipling’s description from the stories. William L. Allen et al., “Why the Leopard Got Its Spots: Relating Pattern Development to Ecology in Felids,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 20 October 2010.

↑ - 10

On art nouveau’s colonial ties, see, for example, Debora L. Silverman, “Art Nouveau, Art of Darkness: African Lineages of Belgian Modernism, Part I,” West 86th: A Journal of Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture 18, no. 2 (2011): 139–81.

↑ - 11

See Preeti Chopra, A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 35–37, 39; Monica Turci, “Kipling and the Visual: Illustrations and Adaptations,” in The Cambridge Companion to Rudyard Kipling, ed. Howard J. Booth (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 169–86; “Research Project: John Lockwood Kipling,” Victoria and Albert Museum, accessed 10 July 2019.

↑ - 12

Rudyard Kipling, “The White Man’s Burden: The United States & the Philippine Islands, 1899,” in Rudyard Kipling’s Verse: The Definitive Edition (New York: Doubleday, 1929), 321–23.

↑ - 13

The meaning of a fluke as a happy accident comes from whaling, when a whale would be caught by the lobes of its tail, called the flukes. Eric Partridge, Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge & Paul, 1959), 217, 223.

↑ - 14

Donald Trump embodies the toxic masculinity and misogyny in real estate culture, as evidenced by so many of his statements. (For example, “Chris, you and I are going to have the meatloaf,” when he insisted on ordering dinner for New Jersey governor Chris Christie, and the Access Hollywood taped remark, “I moved on her like a bitch,” among others.) See Washington Post, 17 February 2017, and 8 October 2016, respectively. For more analysis of this culture and its relation to the fiction of Bret Easton Ellis, see Christopher Burlingame, “Social Identity Crisis? Patrick Bateman, Donald Trump, and the Hermeneutic Maelstrom,” Journal of Popular Culture 52, no. 2 (2019): 330–50.

↑ - 15

Another example of mastery comes from Zeckendorf: “We had a property in Detroit that cost $100,000. It didn’t look like it was going to make any money. So we swapped it for another piece in Brooklyn and a second one in Camden, N.J. and took on a $60,000 mortgage. We then sold that for $60,000. We still weren’t getting anywhere. So I gave the Camden property and $80,000 for a piece in Trenton, N.J. We raised a $100,000 mortgage on that and about the same time sold the Brooklyn piece for $77,000. Then we got out of the Trenton deal for $30,000 and a building on 161st Street, Manhattan, and sold that for $20,000 and finally we had the Detroit turkey off our hands and $50,000 in the bank. Simple.” Quoted in Robert Sellmer, “The Man Who Wants to Build New York Over: A Flamboyant Realtor Named Zeckendorf Plans Cities within a City,” Life, 28 October 1946. Although this anecdote does not fit the pattern of the just-so story, it does illustrate the obscuring power of details.

↑ - 16

Mary N. Woods, From Craft to Profession: The Practice of Architecture in Nineteenth-Century America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999); Mary N. Woods, “The First Professional: Benjamin Henry Latrobe,” in American Architectural History: A Contemporary Reader, ed. Keith L. Eggener (London: Routledge, 2004), 112–31; Sibel Bozdogan Dostoglu, “Towards Professional Legitimacy and Power: An Inquiry into the Struggle, Achievements and Dilemmas of the Architectural Profession through an Analysis of Chicago, 1871–1909” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1982).

↑ - 17

Hilary Ballon, The Paris of Henri IV: Architecture and Urbanism (New York: Architectural History Foundation; Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991); Thomas S. Hines, “No Little Plans: The Achievement of Daniel Burnham,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 13, no. 2 (1988): 104–5; Carl Smith, “‘The Best Thing’: The Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett Collections and the 1909 Plan of Chicago,” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 34, no. 2 (2008): 69–70.

↑ - 18

The literature on professionalization is extensive. See, for example, Jeanne F. Backof and Charles L. Martin Jr., “Historical Perspectives: Development of the Codes of Ethics in the Legal, Medical and Accounting Professions,” Journal of Business Ethics 10, no. 2 (1 February 1991): 99–110; Garnett Laidlaw Eskew, Of Land and Men: The Birth and Growth of an Idea (Washington, DC: Urban Land Institute, 1959); Jeffrey M. Hornstein, A Nation of Realtors: A Cultural History of the Twentieth-Century American Middle Class (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005); Max Weber, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (London: Allen & Unwin, 1930); Harold L. Wilensky, “The Professionalization of Everyone?,” American Journal of Sociology 70, no. 2 (1 September 1964): 137–58; Paul Crosthwaite, Peter Knight, and Nicky Marsh, “Imagining the Market: A Visual History,” Public Culture 24, no. 3 (2012): 601–22, esp. 606; Samuel Haber, The Quest for Authority and Honor in the American Professions, 1750–1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); and Andrew Delano Abbott, The System of Professions: An Essay on the Division of Expert Labor (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988). Crosthwaite et al. discuss the visual representations of markets, as well as the moral impulse embedded in satirical cartoons.

↑ - 19

New York University established the Real Estate Institute in 1967; MIT began the master of science in real estate development program in 1983, and others followed. Some real estate courses had been offered in universities in the United States since at least the 1890s, when Richard T. Ely promoted the academic study of land economics. “Master of Science in Real Estate Development—MIT,” Center for Real Estate, accessed 12 July 2019; “NYU Schack Institute of Real Estate—History and Mission,” accessed 11 August 2014.

↑ - 20

Gary Scharnhorst, Horatio Alger, Jr. (Boston: Twayne, 1980), 44–45.

↑ - 21

The impact of this professionalization project was most notable among the generation of developers who were involved in founding the national organization. On the timeline of the real estate developers’ professionalization, see Stevens, Developing Expertise, chap. 2; Hornstein, Nation of Realtors; Pearl Janet Davies, Real Estate in American History (Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press, 1958). The National Association of Real Estate Exchanges changed its name to the National Association of Real Estate Boards in 1916, holding that name until 1972. Hornstein, Nation of Realtors, 54.

↑ - 22

Stanley Tigerman, “Mies van Der Rohe: A Moral Modernist Model,” Perspecta 22 (1 January 1986): 122.

↑ - 23

His knowledge of philosophy later fueled his conversations with Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

↑ - 24

It is a sleight of hand because they were not so much concerned with moral behavior as with successful behavior. “Freaks of fortune” (see below) were what they wanted to be, not Alger’s heroes.

↑ - 25

Jonathan Levy, “The Freaks of Fortune: Moral Responsibility for Booms and Busts in Nineteenth-Century America,” Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 10, no. 4 (2011): 435–46 (quote, 438); Jonathan Levy, Freaks of Fortune: The Emerging World of Capitalism and Risk in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012).

↑ - 26

The best case for private-sector involvement in city planning legislation is made in M. Christine Boyer, Dreaming the Rational City: The Myth of American City Planning (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1983).

↑ - 27

Homer Hoyt, One Hundred Years of Land Values in Chicago (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933); Carl W. Condit, Chicago, 1910–29: Building, Planning, and Urban Technology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973); Carl W. Condit, Chicago, 1930–70: Building, Planning, and Urban Technology (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974).

↑ - 28

Scholars have traced the origins of expertise to at least the early modern period in Europe, and a growing literature on the topic debates various types and uses of expertise. Interactional expertise does not necessarily reach the higher bar of contributory expertise, which requires competence to carry out an activity. Eric H. Ash, ed., Expertise: Practical Knowledge and the Early Modern State (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010); H. M. Collins and Robert Evans, Rethinking Expertise (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); K. Anders Ericsson, ed., The Cambridge Handbook of Expertise and Expert Performance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006); Evan Selinger and Robert P. Crease, eds., The Philosophy of Expertise (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006).

↑ - 29

Wiebe E. Bijker, Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995); Ruth Schwartz Cowan, “How the Refrigerator Got Its Hum,” in The Social Shaping of Technology: How the Refrigerator Got Its Hum, ed. Donald A. MacKenzie and Judy Wajcman (Milton Keynes, England: Open University Press, 1985), 202–18; Lorraine Daston, ed., Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science (New York: Zone Books, 2004); Bruno Latour, Aramis, or, The Love of Technology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996); Steven Shapin, Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life; Including a Translation of Thomas Hobbes, Dialogus Physicus de Natura Aeris, by Simon Schaffer (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1985).

↑ - 30

Ken Alder, “Introduction (Focus: Thick Things),” Isis 98, no. 1 (1 March 2007): 80–83.

↑ - 31

S. J. Gould and R. C. Lewontin, “The Spandrels of San Marco and the Panglossian Paradigm: A Critique of the Adaptationist Programme,” Proceedings of the Royal Society of London: Series B, Biological Sciences 205, no. 1161 (21 September 1979): 581–98; Alasdair I. Houston, “San Marco and Evolutionary Biology,” Biology & Philosophy 24, no. 2 (1 March 2009): 215–30; David C. Queller, “The Spaniels of St. Marx and the Panglossian Paradox: A Critique of a Rhetorical Programme,” 8Quarterly Review of Biology* 70, no. 4 (1 December 1995): 485–89. See also Malcolm Gladwell, David and Goliath: Underdogs, Misfits, and the Art of Battling Giants (New York: Little, Brown, 2013), with its fairy tale–like constructions that center on the fluke, perhaps the best case of pro-innovation writing pointing to oversimplified solutions. A few reviews of the book point to this tendency. See John Crace, “David and Goliath by Malcolm Gladwell—Digested Read,” The Guardian, 6 October 2013; Daniel Engber, “Gladwell Is Goliath,” Slate, 7 October 2013.

↑ - 32

Leigh Claire La Berge, “The Rules of Abstraction: Methods and Discourses of Finance,” Radical History Review, no. 118 (Winter 2014): 93–112; Leigh Claire La Berge, “Scandals and Abstractions: 1980s Finance and the Revaluation of American Culture” (PhD diss., New York University, 2008).

↑ - 33

“Fashioning a social narrative for abstract information helps traders create understandings of market fluctuations that direct their decisions to enter and exit the market.” Caitlin Zaloom, “Ambiguous Numbers: Trading Technologies and Interpretation in Financial Markets,” American Ethnologist 30, no. 2 (1 May 2003): 264. La Berge also cites Zaloom. La Berge, “Rules of Abstraction,” 96.

↑ - 34

T. J. Jackson Lears, Fables of Abundance: A Cultural History of Advertising in America (New York: Basic Books, 1994), 291–94. Lears states that “the lines between art and commerce, blurred by Barnum and his contemporaries, now seemed to be disappearing altogether. The idiom of entertainment was the eraser” (294).

↑ - 35

Newton A. Fuessle, “What Copy-Writers Can Learn from Story-Writers,” Printers’ Ink 92 (12 August 1915): 36.

↑ - 36

Fuessle, “What Copy-Writers Can Learn,” 33.

↑ - 37

Lears, Fables of Abundance, 291.

↑ - 38

Walter A. Friedman, Birth of a Salesman: The Transformation of Selling in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 80–86.

↑ - 39

Seal, Hines, 29; Gerald Hines and Paul Hobby, “Oral History of Gerald Hines by Paul Hobby,” 13 December 2007, Houston Oral History Project, Houston Public Library; Stevens, “Hines in Houston.”

↑ - 40

Winfried Nerdinger, Dinner for Architects: A Collection of Napkin Sketches, trans. Ingrid Li (New York: Norton, 2004); Hyungmin Pai, The Portfolio and the Diagram: Architecture, Discourse, and Modernity in America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002). Architectural Record began a napkin sketch competition in 2010 and continued it on an annual basis. A short discussion on the parti versus the napkin sketch appears in Norman A. Crowe and Steven W. Hurtt, “Visual Notes and the Acquisition of Architectural Knowledge,” Journal of Architectural Education 39, no. 3 (1986): 6–16. For more on the parti, see Pai, Portfolio and the Diagram.

↑ - 41

Alvar Aalto and Göran Schildt, Alvar Aalto in His Own Words (New York: Rizzoli, 1998), 264; Kendra Schank Smith, Architects’ Drawings: A Selection of Sketches by World Famous Architects through History (Oxford: Architectural Press, 2005).

↑ - 42

Crowe and Hurtt, “Visual Notes and the Acquisition of Architectural Knowledge,” 12. Crowe and Hurtt see the napkin sketch as an almost degenerate form of drawing that is directly linked to the esquisse; I see it as having a different lineage, through engineering and business.

↑ - 43

Trump, Trump, 3.

↑ - 44

Trump, Trump, 66.

↑ - 45

Trump: The Art of the Deal was first published in 1987, the same year as Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities and only three years after David Mamet’s play Glengarry Glen Ross (1984). For analysis of fiction writing of this time period focused on finance, see Leigh Claire La Berge, Scandals and Abstraction: Financial Fiction of the Long 1980s (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015).

↑ - 46

Reinhold Martin points to a clear connection between the economic era and the real estate profession: “Under capitalism, property is the most enchanted thing there is. In this light developers of property—real estate developers—are conjurers, makers of meaning; they are neoliberal capitalism’s shamans, priests, rabbis, imams.” Martin, “Demagogue Takes the Stage.” Many other scholars and critics have recently analyzed Trump’s career and work, including James Graham et al., eds., “And Now: Architecture against a Developer Presidency,” Avery Review, no. 21 (January 2017); Lawrence Vale, “Trumping the Triangle,” Places Journal, 12 March 2019; Belmont Freeman, “Post Trump,” Places Journal, 3 October 2016; Sam Stewart-Halevy, “Medieval Times,” Avery Review, no. 38 (March 2019); and Rachel Weber, “Edifice Rex: Egos, Assets, and the Financialization of Property Markets,” Avery Review, no. 21 (January 2017).

↑ - 47

Trump, Trump, 305–6.

↑ - 48

For more discussion on the abstraction of capital and architecture, see Fredric Jameson, “The Brick and the Balloon: Architecture, Idealism, and Land Speculation,” New Left Review 1, no. 228 (March–April 1998): 24–46.

↑