Exhibition and Erasure/Art and Politics

Fig. 5. Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Holy Land Hotel Model of Herodian Jerusalem.

Photograph by Annabel Wharton, 2006.“History,” however honestly (or dishonestly) compiled by scholars, is deployed only if it has a current utility. History that is irrelevant is forgotten. History that contradicts the currently expedient is erased. These lessons from history can, with a little modification, also be applied to ancient artifacts: objects that reinforce the self-understanding of their possessors are privileged; those that are extraneous to it are removed from view; those that contradict it are reinterpreted or destroyed. This volume assesses acts against cultural property in the Middle East and the Iberian Peninsula from the end of the eighteenth century to the twenty-first century. Here, I offer only the observation that the murder of objects for one set of ideological motives often follows their imprisonment in exhibitions promoting another.1

The politics of archeology in the Middle East are well documented.2 The cultural assumptions of the archaeologist inevitably determine what is uncovered as precious and what is discarded as inconvenient debris. As a Byzantinist, I am all too aware of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century practice of clearing Classical sites of their medieval remains. The Acropolis in Athens provides an example of a site emptied of its Early Modern and Medieval remnants, staging the Classical as its only past. Perhaps less broadly acknowledged: in the museum, as on the archeological site, the professional’s suppositions about what counts as valuable determine how archaeological fragments are documented and displayed. Consciously or unconsciously, the interests that are described through the exhibition of artifacts are those of its curators/possessors. The arrangement and description of objects are intended to persuade the viewing public of the authority of a particular understanding of the past. Archaeology as a modern practice is an invention of the West; so is the museum. Three archaeological museums in Jerusalem—one proposed and two executed—document the ideological work that exhibitions do for those who stage them. Ancient objects, however crude or refined, ugly or beautiful, were produced to work practically, ornamentally, or politically. In modern museums, ancient objects, removed from their original context and function, are forced to act in new ways, often aesthetically and always ideologically confirming and promoting their exhibitors’ Weltanschauung.

The first example is the unrealized project of Patrick Geddes. Trained as a biologist, Geddes was by 1919 recognized as a distinguished town-planner. He was invited to Jerusalem by the Zionist Commission to help plan Hebrew University on Mount Scopus. Once in Jerusalem, he also became a consultant for the Mandatory government of Jerusalem.3 Geddes describes his proposed museum:

Begin then with early Man—Paleolithic, Neolithic and Bronze—and these presented, as far as may be, by local antiquities. But also supplemented and expanded by good reproductions, figures, friezes, etc., as well as by labels and by illustrated guide books. In such a way we come to the Pre-Israelite peoples in Palestine. Thence on one hand to specific Hebrew history, and on the other to the presentment of the great succession of historic cultures, which have surrounded and in various measures affected, both Hebrews and Palestine generally. Begin then with a large Museum Hall for Egypt… The simple visitor should thus see as he entered a good relief model of the whole Egyptian region, with [a] realistic Nile flowing from its reservoirs in the Great Lakes to its outlet on the Sea. Here recall the magnificent realism of the models and panoramas so characteristic of the Paris Exhibition of 1900… [H]ow attractive will be a series of good Relief Models of Jerusalem, illustrating, as far as may be, the extent and character of the city from its earliest Jebusite days, to its glories under David, its greatness under Solomon, and so on throughout its checkered history (Fig. 1).4 In the sketch it will be noted that those Galleries, namely: (1) those of Geography, (2) general history, and (3) of Hebrew and Jerusalem history, all lead into a final Gallery, for the renewing Palestine with its developing Cities and Capital.5

Fig. 1. Model of Jerusalem’s al-Haram al-Sharif by Conrad Schick.

Photograph courtesy of the Museum of Christ Church, Jerusalem.

After an initial appearance of ever-popular Egypt, Geddes’s program emphasizes the “specific Hebrew history” at the exhibition’s core. The program is identified as the product of the nineteenth century exhibition practice by Geddes’s accent on models and reproductions. It is also informed by the tenets of biblical archaeology: “scientific” archaeology in the service of religion, which was dominant in Palestine through the early twentieth century.6 But most notably, the proposed museum seems to suggest the celebration of the modern continuation of Hebrew history in Palestine. Had his project been realized, models and drawings by Geddes, as the author of the urban plan for Tel Aviv, would presumably have been displayed in the final gallery.7 The museum confirms Geddes’s engagement with Zionism.8

The second, fully instantiated exhibition opened in 1938 in the new Palestine Archaeological Museum, an institution funded by the American oil magnate and philanthropist John D. Rockefeller, Jr., owned by the British Mandate government, and administered by a board elected principally from the local Western archaeological foundations. The three galleries at the west end of the building housed extraordinary collections: carved wooden-beams from Al-Aqsa Mosque, the exquisite figural stuccos from the Umayyad Palace at Khirbat al-Mafjar, the lavishly sculptured portal lintels from the Crusaders’ Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and, added later, a small gallery devoted to the display of Dead Sea Scrolls, of which the Palestine Archaeological Museum was the principal owner. The arrangement of objects in the main north-south galleries followed the programmatic practice of Charles Breasted, America’s foremost Egyptologist and founder of the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. Artifacts were laid out chronologically in a sequence of galleries from the pre-historic to the early Ottoman period (Fig. 2). This presentation marked a dramatic shift from the traditional Hebrew Bible-centered formula proposed by Geddes. For Breasted, archaeology’s mission was not to confirm religious convictions, but rather to identify and trace the origins of (Western) man’s cultural evolution:

Between the historians and the natural scientists there has been a ‘great gulf set,’ with the result that we now have on the one hand the paleontologist with his picture of the dawn-man enveloped in clouds of archaic savagery, and on the other hand the historian with his reconstruction of the career of civilized man in Europe. Between these two stand we orientalists endeavoring to bridge the gap… The task of salvaging and studying this Evidence [of the advance of civilization] and of recovering the story which it reveals— that is the greatest task of the humanist today.9

Fig. 2. Jerusalem, Palestine Archaeological Museum, north gallery.

Photograph from Annabel Wharton’s personal collection.

Like its funding and its administration, the project of the museum was Western: the museum’s artifacts were ordered not to prove the truth of the Hebrew Bible, but rather to track the West’s teleological ascent to modernity. In the chronological arrangement of the museum’s wealth of artifacts, the Hebrew phase of history was documented, but received no special attention—it was just one of a succession of societies from the Mesopotamians and Egyptians to Islam that provided the foundations for the cultural achievements of Euro-American man. Breasted’s program complemented the cultural assumptions of the museum’s American benefactor and the interests of its British proprietors. The political conditions have changed dramatically since the museum’s opening. After the Israeli occupation of East Jerusalem during the Six-Day War, the Palestine Archaeological Museum with its history of Western cultural evolution was displaced by the Israel Museum with its emphasis on the region’s religio-national Jewish heritage.10 In the Israel Museum, the first set of galleries splendidly display the museum’s archaeological collection (Figs. 3 and 4). Though objects representative of the regional cultures from pre-historic times through the early middle ages are exhibited, artifacts of Jewish origin are emphasized. The museum’s visitor’s brochure describes the exhibition:

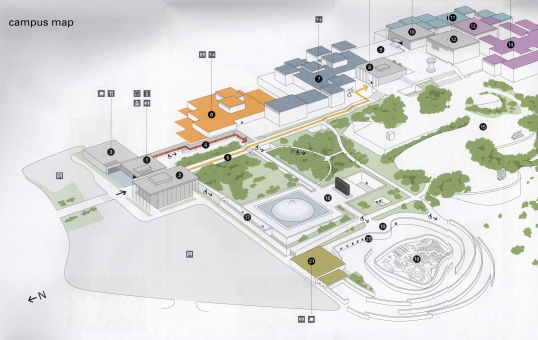

The Israel Museum houses the most extensive holdings of biblical and Holy Land archaeology in the world. The Archaeology Wing tells the story of the ancient Land of Israel… Objects from neighboring cultures that have had a decisive impact on the Land of Israel are exhibited in adjacent galleries.11 The two further sets of gallery spaces are devoted respectively to Jewish Art and Israeli Art. The separate exhibition sites on the campus of the museum further accentuate Israeli control of history. The Shrine of the Book celebrates the museum’s collection of Dead Sea Scrolls. The magnificent Holy Land Hotel archaeological model of Herodian Jerusalem, produced by the distinguished Israeli archaeologists Avi Yonah and Yoram Tsafrir, represents the city during the brief period of its cultural ascendancy before the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E (Fig. 5).

The museum brochure perfectly articulates the institution’s program:

Here [the model of Herodian Jerusalem] provides a three-dimensional contextual illustration for the period documented by the Dead Sea Scrolls, when Rabbinic Judaism took shape and Christianity was born. It also makes a striking visual connection to the Shrine of the Book and to the nearby Knesset, the National Library, and the Supreme Court, symbols of modern Jewish statehood.12

Fig. 3. Jerusalem, Israel Museum, plan from the museum’s public brochure. 1, Entrance; 6, Youth Wing; 7, Archaeology; 11, Jewish Art and Life; 13–14, Israeli Art/Fine Arts; 16, Shrine of the Book; 19, Holy Land Hotel Model of Jerusalem.

Photograph from Annabel Wharton’s personal collection.

Fig. 4. Jerusalem, Israel Museum, view of the exhibition of anthropoid sarcophagi.

Photograph by Annabel Wharton, 2006.

Fig. 5. Jerusalem, Israel Museum, Holy Land Hotel Model of Herodian Jerusalem.

Photograph by Annabel Wharton, 2006.

What the museum does not include in its brochure or on its website is the fact that many of its objects—including most of the Dead Sea Scrolls—making up this Jewish narrative were once held by the Palestine Archaeological Museum (officially renamed the Rockefeller Museum after the Six-Day War), where the story that they were arranged to tell was very different.

These three distinct museum projects all deployed similar objects. Some of those objects are relatively safe and stable: clay pots, Iron Age hardware, and ornamental mosaic floors. These practical objects are recognized for what they are: menial laborers. Other works are more unstable and potentially powerful: the great anthropoid sarcophagi of the Canaanite period, a Chalcolithic scepter ornamented with a ram and ibexes, and the scrolls of ancient writing. These works were originally produced for more elevated, ritual acts. In the museum, they are not allowed to perform sacramentally; they are forced to behave aesthetically and ideologically, each object’s meaning framed by its exhibition context. Those new meanings—Zionist, Imperialist, and Nationalist—cling to them. To most of the museum’s visitors, these meanings are naturalized. The display provides material evidence reinforcing an understanding of history already in place. These museum projects sited in Jerusalem are representative of museums throughout the Middle East. For almost everyone in the West, these institutions are places that preserve admirably crafted artifacts and present them with scientific objectivity. But for a few, museums are cultural impositions of the West. Those few do not understand museums as settings of beautiful things presented as historical facts, but rather as perpetrators of alien ascendancy. For those few, the meanings with which museums burden their objects are pernicious.

Reasoned explanations for the recent widespread destruction of historical monuments and artifacts in the Middle East have been many and various. Economic and political motivations have been explored. More commonly, barbarism, ignorance, and the religious proscription of images are blamed. To these legitimate and familiar accounts of the ravaging of cultural heritage another might be added: the ideological baggage with which ancient objects confined to museums have been encumbered. Those objects that reinforce the self-understanding of their new possessors are privileged. Those objects that are extraneous to the self-understanding of their new possessors are removed from view or sold for monies in support of the regime. Those objects that contradict the self-understanding of their new possessors are reinterpreted or destroyed. The object of history, like history itself, must be able to work for its possessors if it is to endure.

Related Material:

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Annabel Wharton, “Exhibition and Erasure/Art and Politics,” Aggregate 4 (December 2016), https://doi.org/10.53965/EEKA2261.

- 1

The still common understanding of ideology as a consciously constructed agenda of political persuasion was popularized in the West during the Cold War as a description of Marxism. A second, more sophisticated definition of ideology issues from a Euro-Marxist analysis of Western capitalism: ideology masks inequities in the social order by naturalizing them; ideology is a means by which the order of the status quo is maintained. Fredric Jameson, “Ideology and Symbolic Action,” Critical Inquiry 5.2 (1978): 417–422.

↑ - 2

Nadia Abu El-Haj, Facts on the Ground: Archaeological Practice and Territorial Self-Fashioning in Israeli Society (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001); Ran Boytner, Lynn Swartz Dodd, and Bradley J. Parker, eds., Controlling the Past, Owning the Future: The Political Uses of Archaeology in the Middle East (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 2010); Lynn Meskell, ed., Archaeology Under Fire: Nationalism, Politics and Heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East (London: Routledge, 2002).

↑ - 3

Noah Hysler Rubin, “Geography, Colonialism and Town Planning: Patrick Geddes’ Plan for Mandatory Jerusalem,” Cultural Geographies 18.2 (2011): 231–248.

↑ - 4

This model of Jerusalem’s al-Haram al-Sharif was made by Conrad Schick (1822–1901), for the Turkish Pavilion of the Vienna World’s Fair in 1873. Schick was an archaeologist as well as a missionary and architect. The model can be dismantled to reveal the underground passages below the Dome of the Rock. Photograph courtesy of Christ Church, Jerusalem. Such models were much prized as means of understanding sites in the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

↑ - 5

Patrick Geddes, “Jerusalem Actual and Possible: A Preliminary Report to the Chief Administrator of Palestine and the Military Governor of Jerusalem on Town Planning and Improvements,” 1919, File Z4/10.202, p. 29–30, Central Zionist Archives Jerusalem.

↑ - 6

Thomas W. Davis, Shifting Sands: The Rise and Fall of Biblical Archaeology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

↑ - 7

Gideon Biger, “Patrick Geddes and the First Urban Plan of Tel Aviv,” Scottish Geographical Magazine 108.1 (1992): 4–8.

↑ - 8

For Geddes’s emphasis on Zionism, see Patrick Geddes, “The City of Jerusalem,” Garden Cities and Town Planning 11 (1921): 251–254.

↑ - 9

Breasted’s italics. James Henry Breasted, The Oriental Institute, vol. 12, The University of Chicago Survey (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1933), 1–2.

↑ - 10

The Rockefeller Museum is now comatose. For discussion of the museum’s near-death condition, see Annabel Jane Wharton, Architectural Agents: The Delusional, Abusive, Addictive Lives of Buildings (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), Chapter 2.

↑ - 11

“Museum Plan and Information,” (The Israel Museum, 2012).

↑ - 12

Ibid.

↑