DNA Damage: Violence Against Buildings

Fig. 4. The destroyed bazaar of Aleppo.

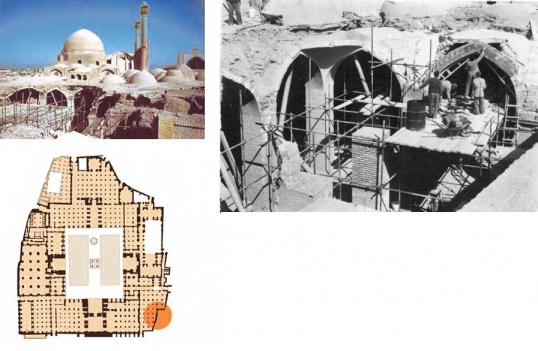

Available at Globoport.During the Iran-Iraq War (September 1980 to August 1988), Saddam Hussein’s fighter jets wreaked enormous psychological havoc among Iranian populations in major cities as far to the east as Tehran, but left seemingly relatively small scars on the culturally significant monuments of Iran. Isfahan, as far as I know, took the brunt of those assaults on historical sites. On March 12, 1984, the Masjid-i Jum`a, the Friday Mosque of Isfahan (a World Heritage site since 2012), and portions of the old bazaar artery that run along the outer fabric of the mosque were bombed. Many lost their lives and panic broke out over the safety, not only of people but also of the marketplace—a key site for the city’s economic well-being. Yet, from the recollection of local memory of that episode, the most harrowing and compellingly recounted was the destruction of parts of the mosque, the segments of the prayer hall that lie on the southeastern side of the mihrab chamber (Fig. 1). Those vaulted spaces, indeed the entire mosque, are among the most spectacular examples of medieval Iranian and Islamic architecture in brick. The mosque had been built in the ninth century after Arab-Muslim conquest of the Isfahan region—possibly on the remains of a Zoroastrian fire-temple. It had been refurbished, with parts rebuilt and entirely transformed over the course of centuries, to stand as the quintessential example of Iranian architecture, representative of the technologies in construction as well as decoration, and of the type of mosque we know as the Iranian four-ayvan mosque (ayvan is a vaulted space that was adapted from pre-Islamic Iranian architecture and spread across the Islamic world).1

Fig. 1. Destroyed part of Shabestan by Iraq bomb attack (MJIB, Jabal Ameli); right: restoring the southeast part of Masjed after bomb attack of Iraqi forces in 1985 by ICHO, with the participation of local craftsmen (MJIB, Jabal Ameli).

Available at UNESCO World Heritage Conservation.

The destruction and rebuilding of the mosque may no longer be as sharply chiseled in the memory of people of Isfahan as it was then, but the impressions I gathered on my first return trip to Iran in 1992 to conduct my PhD research carried reflections on a deeply painful experience. I was shown the rebuilt areas not only by professional conservators, but more importantly by citizens who thought I, especially, should know what happened given that I was coming from “abroad.” This urge to point to the destructions for the outside world to record and report underscores a particularly vexed relationship between the phenomenon of monument defacing and destruction, on the one hand, and media attention—especially foreign media—on the other; this is acutely exploited by both sides in the region under consideration in this volume. Isfahan in those years had become host to a huge number of internal refugees, from among the people of Khuzestan province in southwest Iran and especially the cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr, targets of that same Iran-Iraq war (Figs. 2 and 3). No one, however, pointed to those displaced families, from among whom I knew at least one, the Talebis; I grew up with their son Darius. And those stories of monument destruction could not come near to what I heard from the Talebi family in Isfahan or my relatives and friends in Tehran who told of screaming babies and children held tight in basements during nightly raids, or the babies who did not stop screaming and fidgeting after birth, having “felt” the mother’s fears and traumas in the womb.

Fig. 2. The war-torn remains of a house built by James Mollison Wilson (late 1940s), Abadan, Iran.

Photograph by Pamela Karimi, 2007.

Fig. 3. The war-torn remains of a building allegedly resided by the Shah of Iran during his visits to Abadan.

Photograph by Pamela Karimi, 2007.

We all know and acknowledge that there simply can be no comparison between the destruction of monuments and their attendant trauma and the trauma experienced by human beings who live through such violent environments as wars, and willful and hostile acts of destruction aimed at life. Witness the plight of Syrian refugees now unfolding, in full view of the media—after nearly five years of devastating war and destruction, and the harrowing reign of the so-called Islamic State, Daesh, blowing up the temples in Palmyra, Syria, or old mosques in Mosul, northern Iraq. These are indeed not the same as the story of the beheadings and rapes of the people of Iraq and Syria or drowned children washed onto the shores of Turkey. Yet, something happens when our built environment, especially one that has been in place for as long as our collective historical memory can stretch, is blown up before our eyes, especially before the witnessing eyes of the local inhabitants.

The agonizing difference between the media eyes through which most of us witness such atrocities and the unvarnished spectacle of destruction and violence experienced in situ, must have an impact on those closest to the site that we have yet to appreciate, if only because we do not get to hear their stories. The point here—and this is entirely hypothetical—is to ask whether a sort of PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) associated with the experience of violence may have an equivalent in living through the destruction of one’s built environment—including its highly valued cultural monuments. Are there symptomatic tracings in the people who witness the trauma of monument destruction similar to PTSD? And if such a monument-loss-induced PTSD does indeed occur, is it experienced only by first-hand witnesses or can its effects be extended across the channel of media and affect those who are geographically distant? Can we distinguish between those who lived through the civil war and epic destructions in Aleppo and Palmyra (Syria), for instance, or in Samarra and Mosul (Iraq), Khorramshahr and Ahvaz (Iran), and those of us who are deeply pained by the loss of the monuments we consider world heritage, or the subject of our scholarly lifework, for instance?

The expression of much of our outrage and shock at the destruction of great cultural monuments comes from vicarious, secondhand experiences as researchers, archeologists, and conservationists, and in general as concerned citizens of the world and students of cultural heritage and preservation, be it layman or expert. My obsession with Isfahan as an architectural historian makes it inescapable for me to harbor with considerable emotional intensity the loss of historical monuments. Like all my colleagues who work on pre-modern environments, I have spent my scholarly life rebuilding through tidbits uncovered from historical written sources and from remains of buildings or their urban footprint in the shape of Isfahan as it was in the seventeenth century. No scholarly detachment—objective, cool, however rigorously exercised—can keep one who has grown up in Iran, learned about her histories through monuments, traveled, photographed, and sketched them through the lens of university-age youthful pride and enthusiasm, and has come to work on its monuments as a passionate calling in life, from holding contempt for and anger, oft-unspoken-in-print but embedded-in-feelings, toward historical perpetrators of the destructions inflicted upon the glorious Isfahan. In 1722, Afghan invaders leveled urban quarters (Farahabad) and, according to a late 19th-century source, threw the bookkeeping apparatus of the Safavid (1501–1722) imperial household into the river. The Qajar prince-governor Zill al-Sultan’s abuses of the city’s monuments (the Chehel Sotun Palace) and willful destruction of its gardens and mansions (along the Zayande River and the Chahar Bagh Promenade) came as late as the period between 1874 and 1907.

This sort of breathlessly remembered and passionately felt anger, nevertheless, rarely reaches the same depth of feelings of loss and trauma caused by the destruction of sites of one’s childhood memories of hometown—memories encased and encapsulated with the physicality of the house, the alleyways, the corner store, the maidan (public urban space), the school, the gardens and groves; the neighborhood of a childhood. Mine was not shaped in Isfahan but in Abadan and Khorramshahr, where no major historical monuments existed or were destroyed. Nor, for instance, were Qais Akbar Omar’s childhood memories of Kabul quite the same as those presumably witnessed firsthand by people who lived in the Bamiyan region. The devastation of the war-torn Afghanistan that he recounts in his autobiography includes an affecting story about the famous Bamiyan episode.2 He and his cousins accidentally happened upon filmed footage of the blowing up by the Taliban of Bamiyan’s colossal Buddha statues in March 2001, as they were secretly watching, as it were, a Bollywood movie in his native Kabul. He writes of the shock and anger they felt, the outrage and disbelief at learning of the destruction. He, like me, however, was absent from the scene of the horrifying deed, making his memories of the dynamited Bamiyan statues less compellingly internalized than those of his frightful nights in Kabul.

Abadan was besieged and sustained much damage during that same Iran-Iraq war recounted at the opening of this essay. When in 2005 I went back to Abadan for the first time in some 30-odd years, I found the home where I was born, the ones where I grew up, and many of the haunts of my childhood nearly intact. But elsewhere in the city, much had been restored and replaced, seamlessly masking the destructions and making them invisible except for one set of buildings preserved as reminders of the horrors of that war: they had kept the bullet-ridden western façades of some apartment buildings that faced the enemy city of Basra across the waterway (Basra and Abadan were good neighbors for all of my childhood). It was in Khorramshahr, where we went on weekends to visit my mother’s cousin, or to enjoy cool evening air at a makeshift, river-front café eating grilled sheep’s offal and drinking Coca-Cola, and where we ran around with local children on the riverbank; there, I experienced the loss as viscerally as I had ever known. Khorramshahr was razed to the ground and later rebuilt with not a single shred of its past. No traces of its urban footprint, of a single building; nothing at all of what I still have engraved in my memory as pictures of the streets and my favorite ice-cream parlor and the corner of an intersection beloved for its cheap toyshop. Upon witnessing the destruction of this particular, deeply experienced city, I (the scholar) was one of the people of Abadan and Khorramshahr who had witnessed the destruction of my/their homes and cities. Just as they did, I carried an “architecturally” defined memory that was rooted in personal experience and I was faced with a “monument” trauma. While none of this compares to the truly grisly human cost of that last great war of the twentieth century, it remains worth asking the people of Abadan and Khorramshahr who witnessed the destruction of their homes and cities, if they carry a memory that is “architecturally” defined. And since those homes and cities are as much monuments to the denizens, do they have a “monument” trauma to speak of, to remember and suffer from? That was hypothetical and did not have a name. The section on the proposition of a monument trauma needs strengthening by moving it a bit from the rhetorical question and into a tool of questioning and by proposing the name there.

As this volume asserts, history presents us with a great many examples well before the contemporary tide of violence against monuments. To bring it closer to my “home,” in 330 BCE, Alexander the Great burned the Persian imperial capital of Persepolis to the ground; the Mongol invasions of the first half of the 13th century were spectacularly topped by the siege, destruction, and massacre in Baghdad in 1258, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate (750–1258). In those historical instances, it is nearly impossible to assess the effect of the destruction on people. And yet, as we now know looking back through the lens of history, neither have the ruins of Persepolis disappeared from memory or from the adoring attention of subsequent generations, nor has Baghdad, of which very little survives, become irrelevant, as its great palaces, gardens, and mosques inspired the imagination of poets and builders. The afterlife of Persepolis and Baghdad, and of Isfahan of post-Afghan and Qajar destructions, is the lifework of many who “reconstruct” on paper the histories of those places.

What remains unexplored, or yet to be entertained, is whether any of those traumas have had an intergenerational effect and whether healing of those tribulations and torments inflicted through “monument” destructions have had the capacity to translate into fresh creative acts. The hopeful stance must come from a base of knowledge of the past, its effects, and its full implications for the future. New research through clinical studies has brought forth evidence, still rather controversial, of the relevance of exposure to trauma and the potential for intergenerational transmission of epigenetic modifications to the DNA.3 Epigenetics studies of the cellular and physiological variations caused by external or environmental factors recognize individual responses that translate into altered functional expression of genes, by switching genes on and off. While the DNA sequence may remain intact, the genetic expression of exposure to trauma—mostly studied among PTSD sufferers—may behave in an “intergenerationally transmissible manner” giving us pause in reflecting on the PTSDs of monument destruction. That sort of research could have profound implications for the treatment of the human psyche. In a hypothetical reflection on those bits of knowledge, is it less consequential, one might ask, that Khorramshahr, Abadan, Aleppo, and Mosul were destroyed without having a Palmyra Roman temple, a Nimrud ancient monument, or Bamiyan colossal Buddhas?

Fig. 4. The destroyed bazaar of Aleppo.

Available at Globoport.

The case of Isfahan, where I encountered the new brick vaults in 1992, now seems utterly insignificant compared to what we have observed in Aleppo since the civil war broke out in Syria in 2012. There, too, I spent time just before the war, on a research project on seventeenth century houses—mostly of the Armenian community. I mourn the loss of Aleppo (Fig. 4); but what must the people of Aleppo feel having observed and experienced the horrors inflicted upon them by deranged, deluded, and destructive communities and the regime that raids the city almost indiscriminately from both within and without their city and region? My trauma of yet another loss as an architectural historian—my project was, and still is, on the houses of Isfahan and Aleppo—remains outside the realm of epigenetic modifications. Is there a way for us to think of Aleppine’s response in the long run?

Related Material:

✓ Transparent peer-reviewed

Sussan Babaie, “DNA Damage: Violence Against Buildings,” Aggregate 4 (December 2016), https://doi.org/10.53965/DNHS5974.

- 1

The conservators and architects of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization, under the tutelage of the late Bagher Ayatollahzada Shirazi, faithfully and expertly rebuilt the destroyed vaults, walls, and the adjacent bazaar artery.

↑ - 2

Qais Akbar Omar, A Fort of Nine Towers: An Afghan Family Story (New York: Picador, 2013).

↑ - 3

Rachel Yehuda and Linda Bierer, “The Relevance of Epigenetics to PTSD: Implications for the DSM-V,” Journal of Trauma Stress 22.5 (October 2009): 427–434. I wish to thank Noreen Tehrani for having brought this article to my attention after a discussion we had on August 23, 2015, regarding my “suspicions” of such genetic impact as trauma of monument destruction might entail. I am grateful to her for sharing her reflections based on the clinical experience of helping trauma victims.

↑